Background: Nazism claimed to be a worldview, which was able to provide guidance in all areas of life. Domestic architecture was no exception. This article, taken from a monthly German gardening publication, outlines what a house ought to look like. My architectural vocabulary is not highly developed, and I’m not as confident of this translation as I usually am.

Another article on the site describes Nazi views on interior decoration.

The source: Herbert North, “Das Gesicht des deutschen Hauses,” Gartenschönheit (June 1937), pp. 269-271.

by Herbert Noth

It is consistent with our age and its national problems that we today look and strive for a “German house” that is a visible expression of the homogenous form of life of a people’s community within its common living space. If one takes an imaginary trip through the various German regions, does not one find everywhere those varied characteristics that spring from the depths of our people’s character, that witness to true German culture, and that, taken together, allow us a vivid image of the face of the German house? These houses, as varied as they may be, demonstrate the deep connections that reveal the inner riches of our people and blessed wealth of our living space, in which we want to live together as a family from which strong, courageous, and creative forces will grow. These forces, from their inner necessities, will also influence people’s smaller living spaces, their houses, their yards, their homes, honestly reflecting their times in order to be a strong bridge between the cultural treasures of the past and a new age. This demands more than good workmanship, and it is also more than simply a matter of outward appearances. It is just as much a political task, for we need a deep spiritual cleansing from the confusions of the recent past.

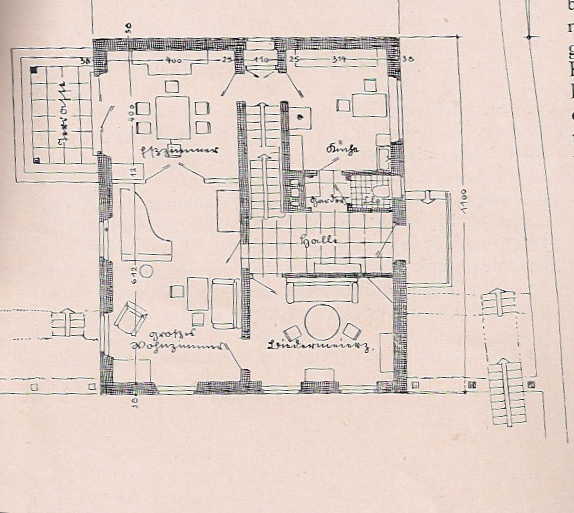

Main floor layout

A new generation desires a clear path from the nobility of the bright past that rejects vanity and showy facades in favor of simplicity and honesty, only from which a new feeling of self confidence can emerge. Such self confidence justifies and requires a respectful pride for the cultural achievements of our forebears and an uncompromising affirmation of the transformation of our living space. We no longer need arguments against the conception of a house as a machine for living [a reference to Le Corbusier’s architectural theories]. When we criticized the Weißenhof development in Stuttgart [a Mies van der Rohe project], it was only to encourage connections to the culture on which we can alone build upon. The famous Swiss architect Bernoulli was mocked for his “Look where one wants, it seems as if architects in Stuttgart are running in panic from the Weißenhof development, hiding in the bushes and dreaming of city halls with iron railings and half-timbered village houses.” It seemed to us that this shot missed its mark, unintentionally hitting another one that we saw as our task. It has little to do with the German house, but is instead only a tragic misunderstanding of real German craftsmanship, even if it is often misused and turned into Kitsch, even if as at the turn of the century untrained hands satisfy the natural desires of broad sections of the population in cheap and dreadfully tasteless ways. Does the fact that many of the “better” houses plaster themselves with ridiculous imitations of metalworking say anything against the honest efforts and exemplary products of true German metalworking? And when we see the familiar plaster frog kings and hordes of dwarves spring to life again from their slumbers in gardens, we have to accept the mockery. We see that some things have gone back too much, missing the bus. Such manifestations are becoming all too frequent, and we need not conceal that broad circles see such Kitsch as a model of comfortable living. One does not deal with the decorative needs of the common people through strictness and classical models, for this can be rejected just as much as a return to nostalgic Kitsch. The plainness of “modern” architecture and the dreadful boring style of many new apartment buildings has caused panicked anxiety, and the bloodlessness of these drawing table products must alarm us.

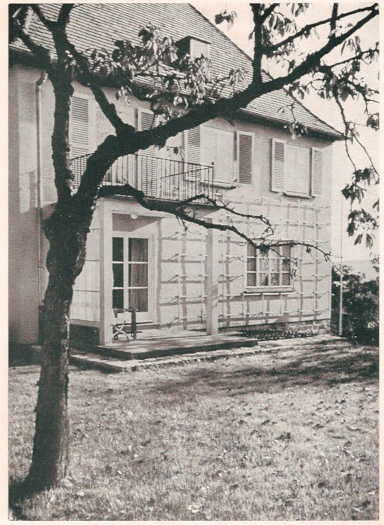

Rear (south) view

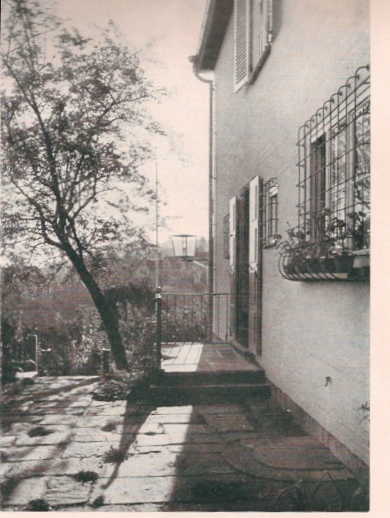

Let us now look at this house by the Saarbrücken architect Rudolf Krüger, which reveals sure instincts. It reflects the specific German nuances of a classic house, fulfilling in the deepest sense the spirit of the bourgeois-German living culture. The German in it is realized in a high style: The fashionable facade of an eighteenth century French house is transformed and enlivened. A simple, clear structure with white walls resting on a stone foundation, and with narrowly overhanging roof fits perfectly into the landscape, as if placed by a sure hand. The windows are arranged in squares against the light walls, and the south side has a trellis. The fruit garden on the lower side includes a stone wall that divides the property in two equal sections.

Front Entrance

The floor plan is as simple as the exterior. There are long lines of sight and good connections between the rooms, demonstrating a sense for the requirements of fine living. The conscious rejection of all external unneeded elements and decorations in the interest of the overall impact allows us to see a new approach to life. It is consistent with the proud appearance of this truly German house.

[Page copyright © 2009 by Randall L. Bytwerk. No unauthorized reproduction. My e-mail address is available on the FAQ page.]

Go to the main page for the book

Go to the 1933-1945 Page.

Go to the German Propaganda Archive Home Page.