Background: Signal was a twice-monthly propaganda publication

by the Nazis that appeared in numerous languages. This is a translation

of a special edition that accompanied the issue #11/1944, issued late

in June after D-Day, and after the Germans began launching V-1 rockets

toward England. Germans had been longing for the promised miracle weapons and this issue was surely read with eagerness. The article provides few

actual details on the V-1, instead presenting it as a terrible but justified

response to Allied bombing of Germany. For an article published a week

or so after this, see “First

Results of the V-1.” See also Goebbels’s

essay on the V-1 in Das

Reich.

Background: Signal was a twice-monthly propaganda publication

by the Nazis that appeared in numerous languages. This is a translation

of a special edition that accompanied the issue #11/1944, issued late

in June after D-Day, and after the Germans began launching V-1 rockets

toward England. Germans had been longing for the promised miracle weapons and this issue was surely read with eagerness. The article provides few

actual details on the V-1, instead presenting it as a terrible but justified

response to Allied bombing of Germany. For an article published a week

or so after this, see “First

Results of the V-1.” See also Goebbels’s

essay on the V-1 in Das

Reich.

The source: “Warum Deutschland nach England schießt,” Signal Extra, Late June 1944.

England’s Way of Waging War: The beginning of revenge on the island

One of the most remarkable scenes in modern English history is undoubtedly 18 June 1815 when the Battle of Waterloo was nearing its end after several days. We do not mean Marshall Blücher’s famous thrust at Napoleon’s army’s right flank that occurred just as Wellington had committed his last reserves, but rather the scene in London the following day. While the battle raged on the Continent, England’s financial magnates gathered at the London Stock Exchange. The outcome of the battle would determine whether those who had speculated on a fall, or those who had gambled on a rise, would make a huge profit. It is well known that the English branch of the House of Rothschild, which had a well-developed intelligence system, laid the foundations of its wealth that day.

When Winston Churchill told the House of Commons at the end of May this year that,as the result of its neutrality, Turkey would not have the strong position at the end of the war that it hoped for, a prominent Turkish member of parliament commented in a newspaper article that Turkey was not accustomed to determining friendships between peoples in the same way as stock exchange speculators, changing the value of other nations daily as dictated by events. This Turkish comment hit at the center of the unchanging English national character, which is incomprehensible to continental peoples. This would be made clear again only a few days later.

The invasion began in the early morning of 6 June. The next day, an American correspondent reported wild scenes at the London Stock Exchange immediately after the news became known. Some stocks nearly doubled within a few hours. There was a run on the shares of large English armaments firms, but also on those of the railroad in Northern France. Later, an English war correspondent wrote: “If I had been able to crawl over there after reaching land from the wreck of a landing boat, I would not have been able to write another thing.” Thousands of British solders who only the weekend before had taken leave of their mothers and wives were dead. They did not learn anything further about the goings on at the London Stock Exchange.

The battle in which England’s soldiers fall. A big trading day at the stock exchange.

In his Paradoxes sur l’avenir de l’Europe, Albert Mousset writes: “England is more upset about the decline of its currency than the defeat of its soldiers.” It is clear that this unchanging British approach to war is different than that of continental peoples.

As Lloyd George wrote in his memoirs, during the First World War the hunger blockade against women and children was the only means that finally gave England success. In this Second World War, England uses fire bombing, high explosive bombs, and mines on thickly populated cities to destroy peoples. The English go by the grim principle: “Everything is permitted in war.”

After years of waiting, Germany began giving a frightening reply on the night of 15-16 June. The moment it began, the island was cut off from all contact with the outside world. One could no longer conceal the powerful effects of the first German revenge weapon that drove the citizens of London and Southern England into the shelters not only for hours, but for a long period of time. From that moment, it was clear that the war is not only a matter for speculators for whom a few young men must unfortunately be risked, but rather that just as England and America had unleashed a war of destruction, so, too, they were facing a war of destruction themselves.

The deeper significance of the events is shown by certain Englishmen, who already sense that the game they played in the past is over. Recently, for example, the Reverend W. R. Inge asked in the Daily Standard of England will cease to be a great power: “To some degree, we must cease being the world's policeman and stop giving our neighbors moral lectures.” Reverend Inge means that Russia, not England, will dictate the peace, that it will be the dominant power on two continents for a long time to come. That is not all that bad for England, however. It will have to reconcile itself in the future to become an agricultural nation once again!

Those on the Continent will see W. B. Inge’s conclusions from a different standpoint. The resignation in his words is an admission that England’s most modern weapons of destruction will not bring success. It is the resignation of those who realize they cannot halt fate’s inevitable results.

For the first time in history, the British way of war is backfiring. For the first time in centuries, those in the ruins of British cities will have to contemplate where their approach to war has led, a method that England has always used against the European continent.

Why does Germany fire on England? Because despite four years of warnings, it conducts open aerial warfare on civilian populations. England does not want a battle of army against army, as was formerly the practice among Europe’s civilized peoples, but rather a war of extermination aimed at a people’s very substance.

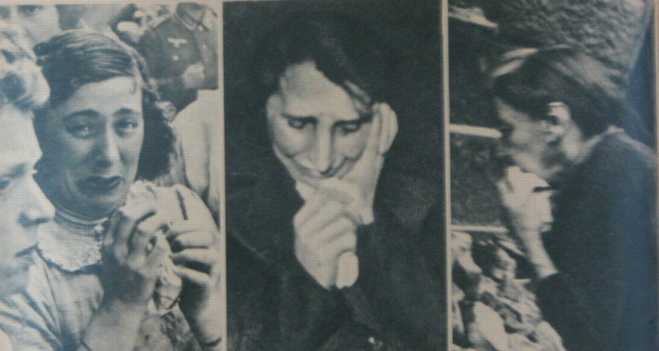

Mothers in France, Germany, and Romania

grieving their dead children.

Mothers in France, Germany, and Romania

grieving their dead children.

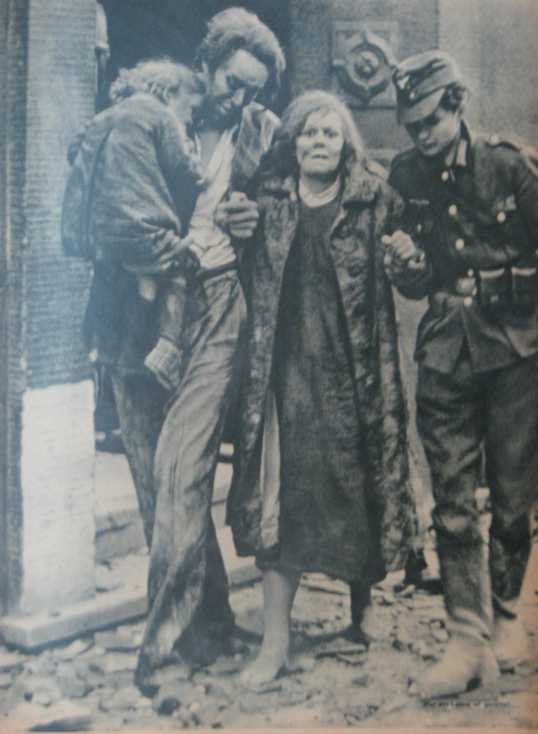

For four years, it has been the same picture. After a terror attack...

She escaped with only her life...

A representative picture: Streets

in a housing district of a German city. Germany fires on England because

of the dead under the ruins.

Another representative picture: A snow-covered

farm, hit by a well-aimed bomb. Systematically, just as with the housing

districts of cities, the English aim at the farmer, his livestock,

and his harvest. As in the First World War, the goal is to starve Europe.

Another representative picture: A snow-covered

farm, hit by a well-aimed bomb. Systematically, just as with the housing

districts of cities, the English aim at the farmer, his livestock,

and his harvest. As in the First World War, the goal is to starve Europe.

In Paris, English planes use machine guns to fire on those attending a memorial service for the victims of English air terror.

What Led to 16 June?

He who was listening to German radio on the afternoon of 17 June 1944 heard what probably was the most sensational and grimmest report ever broadcast during this war. For many minutes, one heard the full roar of the “new explosives” flying toward England.

We heard it in the middle of the ghostly ruins of Berlin. The radio’s sounds came out of a small shop that had been set up in a destroyed building in the middle of a district in which hardly any of the large buildings existing before November 1943 are still standing. The few pedestrians still walking through this destroyed street stood still and listened to this peculiar deadly music. These Berliners immediately understood that something similar had never happened to their miserably destroyed city. They looked at the ruined streetcars. No one in the world can understand better than these Berliners what this means for those in London and Southern England. It would be wrong to say that these Berliners cheered. What they had experienced in their own city made them far too serious for that. During months of the most severe trials, the phrase “secret weapons” had never lost its metallic sound. In England, people had assumed it was only a bluff, since nothing had happened nine nights into the invasion. After the tenth night, however, no one in London or Southern England had to try to solve the riddle any longer.

We remember that on 31 March 1936, the Reich government made another in a series of proposals to European and world governments, which among other things said:

“The German government sees its most important task at present as bringing aerial warfare under the same humane and moral conditions as the Geneva Convention currently gives to neutrals and injured soldiers. The killing of defenseless casualties, the use of dumdum bullets, and unrestricted submarine warfare are regulated or forbidden by international conventions. In the same way, civilized humanity must restrict the use of new weapons to prevent the senseless extension of warfare.

The German government, therefore, proposes for such a conference the following practical goals:

1. The banning of gas, poison, and fire bombs;

2. The banning of any form of bombing on any locales that are beyond the range of medium artillery along the fighting front.”

The French government considered this proposal seriously at the time, but England rejected it. At the time, the later Air Marshall Harris was testing the effects of carpet bombing on the natives on India's northwest border and in Southern Arabia.

The Reich government made similar proposals after that, and on the day the Polish campaign began, the Führer announced that he had given the Luftwaffe orders to limit its attacks to military targets. Adolf Hitler said then: “If, however, our opponent thinks this means that he is free to use such methods himself, he will receive the appropriate reply that will teach him a lesson.” Nonetheless, England began bombing in spring and summer 1940. After weeks of waiting, the German Luftwaffe made its first terrible replies in what the Londoners later called “the blitz.” After 1943, the English and Americans again had the upper hand in the bombing war. They destroyed not only Germany's housing districts, churches, theaters, and museums, but also those of Italy, France, Belgium, Holland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria, and to a lesser degree those of Denmark, Norway, and even Schaffhausen in Switzerland.

While this destructive war against European culture was going on, England was repeatedly warned that German flak and German day and night fighters were not the final German answer. Still, they continued to destroy Berlin, Rouen, Milan, Hamburg, Lübeck, Sofia, and Bucharest. Dozens and dozens of European cities were destroyed, and thousands of civilians lost their lives. Hundreds of thousands lost their house and home, and all their possessions.

And today, we say with all the seriousness of someone who knows exactly what he is talking about, that what began with the bombing of Southern England and London on the night of 15-16 June was not the final German answer.

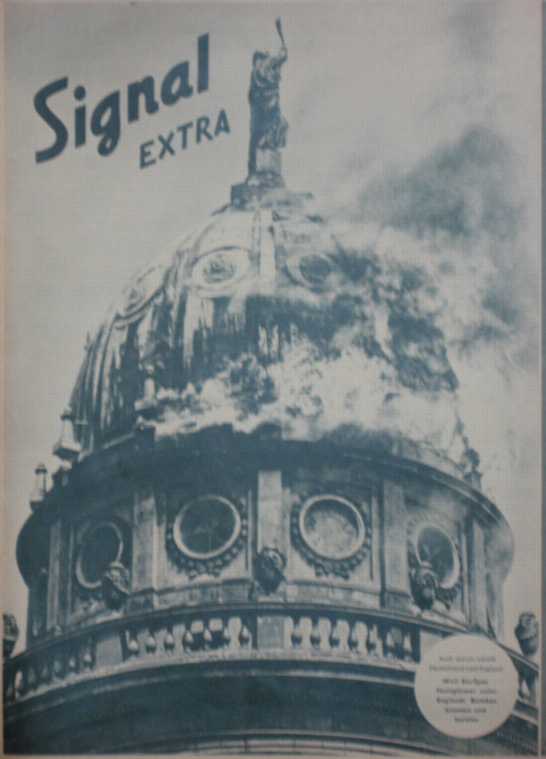

Another reason why Germany fires on

England: Bec ause Europe's holiest treasures burn and collapse under England’s bombs.

ause Europe's holiest treasures burn and collapse under England’s bombs.

Last edited 25 April 2025

Page copyright © 2008 by Randall Bytwerk. No unauthorized reproduction. My email address is available on the FAQ page.

Go to the Signal page.

Go to the 1933-1945 page.

Go to the German Propaganda Home Page.