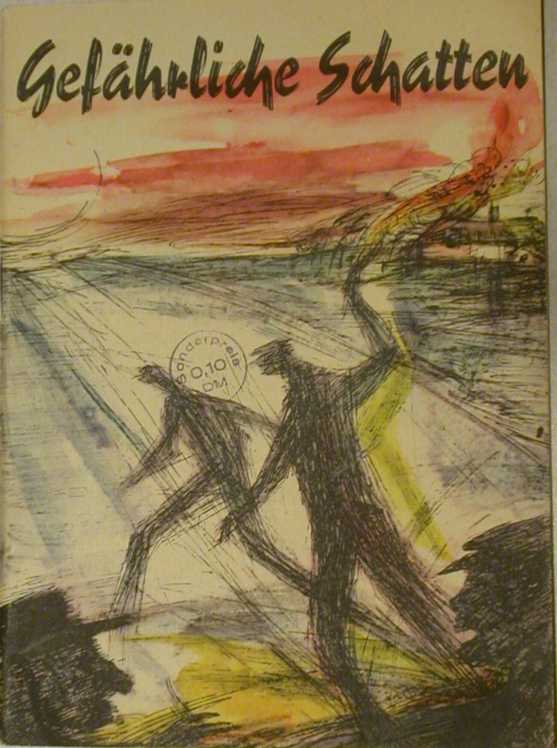

Background: This little pamphlet is a lovely example of GDR agricultural propaganda. It suggests that the collectivization of agriculture, bitterly resisted by many farmers, was the wave of the future, and that old Nazis from West Germany were doing all they could to resist. This was published by the Ministry for State Security, the Stasi, which is portrayed as a vigilant force countering enemy activity.

The source: Gefährliche Schatten: Eine Erzählung nach Tatsachen über Schädlingstätigkeit in der Landwirtschaft (Berlin: Ministerium für Staatssicherheit — Agitation Department, 1960).

No one would be foolish enough to try to empty a lake like the Müritz with a soup spoon. One could work for seven years and seven days without reducing the water level by seven millimeters.

Even

more foolish is the attempt to slow or even halt the victorious march

of socialism.

Even

more foolish is the attempt to slow or even halt the victorious march

of socialism.

Still, there were such people in Zepkow. They joined together to attempt to hinder the socialist transformation of agricultural production in this and neighboring villages.

Socialism, however, has laws that govern human development. It is not to be halted, nor does it make a detour around the farming village of Zepkow in Röbel County.

The big reactionary farmers in Zepkow did not want to accept that. They sought and found willing tools who through sabotage attempted to ruin and finally liquidate the young socialist system of production.

Using all the advantages of the “Front City” West Berlin, they directed and led their counterrevolutionary underground group, supported by the spy central and other organizations of the western zone’s clerical-military dictatorship.

The attempt by the Zepkow fascists failed. It had to fail, since a handful of reactionaries were attempting to halt the will of the workers of the community.

It had to fail, because there are socialists in Zepkow, because Zepkow is a village of a workers’ and farmers’ state.

A die has six sides. When it lies on a table, only five sides are visible. But we have to review the sixth side. This sixth side is Zepkow’s past . . .

There were ten tenant farmers in Zepkow in 1900, since the land, organized in domains, belonged to the Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. They had to lease their land. There were also 25 small farmers and 19 households that could hardly feed themselves from their scraps of land.

The November 1918 revolution changed the situation for the better only for the ten tenant farmers. They could now buy their leased land. The small farmers and householders remained poor. Their sons and daughters had to work for the big farmers and hardly earned a thing.

The big farmers had their old economic power. German Nationalists from head to toe, they opposed any hint of progress, but they supported the fascist newcomers. They founded an S.A. unit in 1932, and shortly thereafter, a local group of the Nazi Party.

One of the first and most brutal Nazis was Karl Flick, owner of three hundred acres of land. He and his cohorts dictated what would happen — imperially, inhumanely, brutally.

Zepkow became a fascist stronghold in Mecklenburg.

The Reich Youth Leader Baldur von Schirach came here to speak at the Hitler Youth school in Wredenhagen.

Prisoners from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp were forced here. It was a death march. Many honorable antifascists were gunned down in the forest at Below . . .

This will help one to better understand what happened after 1945 in Zepkow.

The harvester throws the potatoes to the surface of the field, a lot of them. The agronomist mutters angrily as he inspects them: “Worthless, they’re all worthless.”

Scales cover the potato skins. They are supposed to be valuable produce, intended for export to other socialist countries.

The whole eighty acres was not exportable. The cost would be huge!

“Freshly limed soil,” the agronomist determines. “How could such an experienced man like Paul Binkowski behave so stupidly? I can’t understand it.”

A year earlier, the early potato “Sieglinde” had been planted. It grew well, promising a fine harvest. But as it was tilled, the potatoes were scaly.

“Just like before,” the agronomist said. “It’s a shame.” He quietly begins to doubt the wisdom of LPG [collective farm] director Binkowski . . .

And not only him . . .

In the fall, when harvest helpers came, they were given nonessential jobs to do, or send away, while sixteen acres of potatoes froze — “forgotten.”

That’s almost sabotage,” the agronomist thought. But who did it? Who is the guilty one?

In Summer 1956, the Agricultural Production Cooperative “Jupp Angenfort” had a herd of forty TB-free young cattle. But one day they were driven into a paddock surrounded only by a weak fence. And there was a cow with TB in the neighboring field. The animals broke through . . . The county vet found that ten of the young animals had been infected.

You can’t put them next to each other,” the veterinarian told the livestock supervisor Erich Degenhardt. “Let that be a warning to you.”

With increasing frequently, cattle have to be slaughtered. The diagnosis is always the same: hepatitis. Such animals do not count toward meeting the LPG’s plan. If only they had been delivered on time . . .

What can Erich Degenhardt do about it?

Does he not take exemplary care of the animal in the stalls of the fugitive farmer Paul Flick?

But somehow, somewhere, the enemies of socialist agriculture are at work.

Shadows have fallen over Zepkow, the farming village in Röbel County, Neubrandenberg. The Agricultural Production Cooperative [abbreviated LPG, a collective farm] is simply not making progress. Setback follows setback . . .

The private farmers are talking: “An LPG? Look at Zepkow! We should want to become part of that? No thank you!”

What is happening in Zepkow?

Are the right things being done?

The right things are not being done — and it all starts four years ago, on an April night in 1953 . . .

There was a light tapping at midnight on Erich Degenhardt’s window: once, twice. When Degenhardt opened it, Heinrich Heidemann and Horst Flick were standing outside the door. Without waiting to be asked, then came in.

“Go to the chief immediately,” Heidemann demanded.

While Degenhardt put on his jacket, he asked himself what Paul Flick might want. But thinking too deeply was not his style . . .

The big farmer’s front room is a little too open. Some of the furniture is missing. What’s up? Paul Flick greets his tractor driver. “Good that you came fast. It’s a bit unusual to have you over at midnight. Can’t be avoided at times.”

He takes out a packet and offers a cigarette. “A good one, from the other side [West Germany].

“What’s going on,” Degenhardt wonders.

“What I wanted to say — how long have you been working for me, Degenhardt? Since 1926?”

“Yes, since 1926,” the tractor driver replies. I started as a stable boy.”

“Right, right,” the farmer said, “with the horses. Twenty-seven years ago. How fast time goes — Another drink? You too, Heinrich?”

“Good schnapps,” Degenhardt feels he has to say.

“Heinrich, turn the radio on.”

Chopin fills the room, but nobody listens.

“I want to put you in charge of the farm.”

Erich Degenhardt cannot believe what he hears. He run the Flick farm? What does it mean? “I can’t stay around here any longer. They’re sitting around waiting for deliveries and who knows what. I have to disappear . . .”

After talking for two hours, Paul Flick and Erich Degenhardt come to an agreement. Degenhardt gets the big farmer’s house and will carry on the business. The buildings are not to be altered, and land is to be cultivated well, the animals cared for properly . . .

“I won’t stay in West Berlin forever. My tent won’t be there long. I’ll be back, and then . . .”

“You can rely on me, chief,” replies Degenhardt.

“Keep me informed how my farm is doing. And I’ll be interested in what is going on in Zepkow. One wants to know what is going on back home . . .”

Another shot of schnapps.

“Keep a stiff upper lip, Degenhardt!”

On 29 April 1953, farmer Paul Flick leaves his village. He heads for West Berlin.

“If there’s anyone we can rely on, it’s Heinrich Heidemann,” Flick says. I say that not only because he is my son-in-law. He has remained true to the old flag, one of the few.”

“Good,” replies Trothau. “I’m not blind.”

Fritz Trothau knows his people from before 1945.

He did some business with the farmers in Zepkow when the black market was still flourishing.

Yes, he knows what to think of Paul Flick and his cohorts.

“When is Heinrich coming to Berlin? Schlundt has a job for him.”

“I’ll write him,” Paul Flick promises.

Heidemann is reliable . . . He joined the German Jungvolk [the Nazi organization for young boys] in 1938, and three years later the Hitler Youth. Troop Leader Heinrich Heidemann eagerly went to military training camp, and three weeks later volunteered for the Waffen-SS. Scarcely seventeen years old, he wore the notorious death’s head uniform of the “Wallonia” Division.

His father’s farm was ten hectares as Heidemann took it over in 1949. But he knew how to double its size quickly. Paul Flick one of the most prosperous big farmers in the area, was to willing to let Heidemann marry his daughter Elise.

The SS man was careful in his choice of wife. Her father Paul Flick was a firm Nazi, and her mother had been the Scholtz-Klink [Gertrud Scholtz-Klink was the leader of the Nazi women’s organization] of Zepkow.

The refugee Kulak [the Russian name for a prosperous farmer] could surely rely on him.

Heidemann and Degenhardt went to West Berlin on Ascension Day 1953. They met in Trothau’s apartment with the big farmers Paul Schmidt and Adolf Schlundt. While Degenhardt was getting new orders, Heidemann pulled Schlundt to the side.

“Go to Karl Flick. Tell his daughter to visit me at once.”

“Horny bastard,” Heidemann thinks. Still . . . To him, Schlundt is still local group leader of the NSDAP, and an order is an order.

“Will do!”

“By the way, it won’t be much longer before we strike. Get things ready. This time We’ll make a clean job of it.” Schlundt grins: “We don’t forget!”

The other Flick, Karl Flick, has been living with his family since Whitsun in West Berlin. His good friend Fritz Trothau is giving him a place to stay until he is recognized as a “political” refugee. Such recognition is not hard for a former local farmers’ leader and community leader to get . . .

“A certain Binkowski wanted to speak to you,” Trothau says.

“Binkowski?” Flick is astonished. He had authorized the old guy to watch his farm. What did the tractor driver want? “What sort of man is he?”, Trothau inquires.

He’s been working for me only since 1948. A hard worker who knows something about plant and animal production. Worked for years with Lowzow in Schönhagen.

“And?”

“No way he’s a communist.”

Trothau raps in annoyance.

“You’re thick, Karl. You leave that old cow of a stepmother behind, 80 years old, but don’t think about Binkowski. We need him! The Reds like agricultural laborers.”

Soon after this conversation, Paul Binkowski returns to the farm. He has become its director — by the grace of Karl Flick.

Letters tell him how to run the farm. He follows them, since he believes the big farmers will return.

RIAS [Radio in the American Sector, a radio station in West Berlin that had a big audience in East Germany] is not intended for the American sector of West Berlin — least of all for it. If Heinrich Heidemann wants to know that the Kulak lords are thinking, he does not need to visit Fritz Trothau . . .

The evening before 17 June 1953 [the East German uprising against Marxism], he and farmer Kracht had written a proposal to the states attorney of Röbel asking that the former Zepkow dairy manager, convicted of criminal activities, should be released and restored to his former job. He intended to use every means to collect signatures from the farmers. More than that. He found several dubious characters and went to the county seat with them.

He paid for the trip.

“Just wait,” he prophesied. “Tomorrow the communists may be gone. One must only . . .”

But there were no farmers willing to give their land back to the Junkers.

Months later, Heidemann got those of like mind together in the village pub. The defeat of 17 June was eating away at him. He had to vent his hate.

“Comrades! No one thinks any longer of honoring our comrades who fell in World War I. They lay piles of wreaths for Germany’s enemies. But they forget our heroes, who made Germany great . . .”

That evening, the SS men decided to place two wooden iron crosses at the memorial for World War I.

Trothau is not particularly pleased. In fact, he is angry.

“What are these idiots doing? Does he want the police on his tail? Nothing comes of such nonsense. Absolutely nothing. We have to do things differently.”

“You’re right, Trothau,” nods Schlundt. “Heidemann shouldn’t think the communists are stupid. My farm is worth more to me than such a worm-eaten cross.”

“At least Degenhardt and Binkowski aren’t such hotheads,” says Karl flick. “They have become state-recognized managers . . .”

“But I don’t quite trust Binkowski.”

“Why?”

“He’s got seven kids . . .”

“Laziness?” Fritz Trothau looks searchingly at Binkowski. “No, my dear friend. He who says A must also say B. Or?”

“But it isn’t simple . . .”

“But, but . . .” interrupts the agent harshly.

“Are you the manager of Flick’s farm or not?”

“Sure, but the öLB leader gives me directives.”

“And you can’t get around them?”, says an unknown man whom Trothau had introduced as a friend. “If you spent the whole war on the farm and avoided the draft, you must know a lot. Play your trump cards, man!”

“We’ll be back in six months at the most,” Trothau says threateningly. “Think about that, Binkowski! You’ve got a family and seven kids, yes?”

Binkowski had spent his life working on farms owned by top army officers. He was used to orders. Carry them out. He was something of a sergeant in civilian garb, since he trained Herr von Lowzow’s apprentices.

Paul Binkowski had no desire to earn the displeasure of his superior . . .

Back in Zepkow, he cleverly spread the rumor that the big farmers would soon be back. That intimidated the workers, since they had been under the big farmers for a long time.

Still, neither he nor Heinrich Heidemann could stop the Agricultural Production Cooperative “Jupp Angenfort” from being established on 14 April 1955. But he did achieve something: the farmers elected him vice chair and made him field supervisor.

Now they will want to bring the nine farms together,” said Heidemann. “But we have to stop that. If we succeed in that, We’ll be OK.”

“I’ll try,” promised Binkowski.

“Well, we do have the field supervisor, that’s something — things still look good for us. Let’s celebrate.”

There was a man in the way of those sitting on their packed suitcase in West Berlin: the LPG director.

“We don’t like that guy. See to it that he disappears from Zepkow as soon as possible,” Fritz Trothau was told, and he passed the order on to Heidemann.

“But don’t do anything careless, Heidemann, no big fuss or anything,” warned Trothau, who had become an agent of the notorious Investigative Committee of Free Journalists. “You have to undermine the LPG director’s influence. Do things that make his life in the village impossible. Stories about women, etc. If the collective farmers get rid of the guy on their own, there isn’t much the party can do about it, and we’ll have won.”

“Good luck! Hail and Victory [a Nazi slogan].”

“And rich booty! Trothau clapped Heidemann on his shoulder: “Man, if it weren’t for us old guys . . .”

A rich harvest waits on the fields, splendid grain on the stalk. And the fields look made for the harvester.

“Now, Binkowski, show us the kind of man you are,” Heidemann says to the field supervisor. “Prove to the collective farmers that the director hasn’t the foggiest notion of farming . . .”

Binkowski grins knowingly. He’d already done a few things to weaken the reputation of the LPG. If the director hadn’t been so clever, half the animals would have starved that spring. Now he has a new plan.

The harvester begins to clatter ceaselessly, devouring the grain.

Binkowski rubs his hands at the edge of the field.

“Well, director, your Russian machine alone can’t do it. Where will you get the people to bind the sheaves,” he said maliciously.

“That’s what comes of having a big city boy as director,” the Kulak lackey laments hypocritically a few days later, after he has thrown the entire harvest into disorder. “But he does it all by himself rather than ask me. The director always knows how to do things better.”

With such subversive talk, Binkowski succeeds in turning some of the collective farmers and tractor drivers against the LPG’s director. Finally he thinks it time at a meeting to say: “Why aren’t things progressing with us? I think it is because we do not have the right man at the top. We need work, not talk. And one has to know something about agriculture if anything is to happen.”

The throne is shaky, Heidemann note at year’s end.

“The big farmer will be satisfied,” Binkowski replies.

“Not quite yet. You have to become their favorite. You have to . . .”

“It’s clear. I’ll become director, and I’ll take care of him.”

“Degenhardt will propose you. I’ve worked it all out with him. He’ll be second in command. Then we’ll finally have the right team. By the way, just between us, the Reds won’t be around much longer. I’ve heard some information.”

“Another 17 June?”, Binkowski asks with interest.

“Nonsense! No point to that. We’ll do it differently this time.”

“How?”

“How? Well, do you think that our people in the West will leave us in the lurch? Why are they rebuilding the Wehrmacht? All it will take is a signal, and we’ll be at the gates of Warsaw. There will be a big house cleaning.”

By January 1956, the Kulak lackeys Heidemann, Binkowski, and Degenhardt have done what they planned, and what they were supposed to do: the “experienced and careful” Paul Binkowski replaced the former LPG director. His second in command and also livestock supervisor was Degenhardt. They drank until dawn.

Who among the collective farmers knows what is going on in Binkowski’s mind? Who knows that he has been ruining tons of grain, that he is doing damage wherever he can . . .

Who knows of the letters that Karl Flick sends him?

And who knows the real Erich Degenhardt? No one knows what he is doing to keep the farms of the nine big farmers who have fled in their original state. No one notices that Flick’s cattle are better cared for than the others.

The shadows over Zepkow grow darker.

“Well, Heidemann, what’s up in Zepkow? I heard the Reds are having some problems.”

With these words, Adolf Schlundt greets the messenger.

“Binkowski has become director,” Paul Flick reports proudly, “and Degenhardt is his assistant.”

“That’s great,” Schlundt grins. Heidemann reports every last detail of what is going on in the village and the LPG. He concludes by noting that a pig stall is being rebuilt to raise cattle.

“What’s Binkowski doing? Our stalls aren’t to be touched! Tell him that, otherwise . . .” Red with anger, the former Nazi leader clutches a package of cigarettes. I’ve clobbered others before . . .”

Heidemann knows Binkowski better.

“If he fights the LPG too openly, he’ll be out. They’re not stupid.”

“Don’t worry. He won’t have to worry about State Security and mess with things that don’t concern him.” “Well, you sit here in safety and can open your mouth,” Heidemann thinks. Then he relates the story of the scaly potatoes, which were his work.

Paul Binkowski feels like the Lord of Zepkow. He is not interested in the advice of the chief agronomist from the MTS [Machine Tractor Station — an attempt to centralize the holdings of agricultural equipment] or the advice of state functionaries. Of course, he always nods eagerly and complains about the problems — which he quietly and secretly is causing.

He lets the land and meadows go to seed, lime and fertilizer decay, weeds grow. The harvest falls continually. In 1956, 120 decitons of potatoes are harvested per hectare, only 73 in 1957 . . .

He uses valuable seed as feed or doesn’t even harvest it. Grain rots in the fields. Field edges are plowed under. In 1956, Binkowski takes 127 decitons of oats and 81 of rye for the plan from that were supposed to come from the big farmers, but takes it from the smaller farmers instead. The next year, it is 256 decitons, without receipt or payment.

“You’re smarter than I am,” Heidemann says. “Keep it up!”

And Degenhardt?

He’s made repairs to the perfectly fine roof at Flick’s farm, and painted the doors and windows.

“If he could only see how good his farm is looking . . .” Erich Degenhardt is firmly convinced that his master will return. He also takes particularly good care of Flick’s livestock.

In January 1956, Paul Flick makes a sudden appearance in Zepkow!

Degenhardt happily led the big farmer on an inspection tour of the farm. “Well, chief, have I kept everything in order or haven’t I?”

In answer he received a cigar, a Western cigar. It had cost 30 pfennig! “You know, Heinrich, this Degenhardt is a great guy,” the Kulak said. “I think we can do a little more damage.”

Heinrich Heidemann said nothing. He walked silently beside his stepfather.

“Why aren’t you saying anything?”

“There are others in the village. We have be careful. The SED [East German Communist Party] people . . .”

“Hey, the farm workers are immune . . .”

“But it would be better for Degenhardt to join the party.”

“That’s asking a lot. It won’t happen. Never.”

Paul Binkowski sensed that Heidemann had probably been right when he cautioned him a year ado about the workers Hiller and Rybaschewski. Sometimes when he was returning home drunk, he thought he was being watched. Then he sped up . . .

“Who can prove anything? I’ve always burned Flick’s letters immediately,” he told himself. “What can Karl Hiller do just because I denied him permission to rebuild Karl Flick’s stall? Not a thing. They can build new stalls . . .

Not a thing they can do to me.”

In 1956, Binkowski had put in fourteen acres of corn. The agronomist hadn’t budged in demanding that he plant it . . .

“Corn! That stuff grows in Hungary or the Ukraine,” he said, “but not here in Zepkow. What do you think, Degenhardt?” He nodded. Still, the corn was planted. But it did not want to grow.

“You picked the wrong field,” the agronomist said.

Binkowski was brusque. “The wrong field? Nonsense. I knew that weed wouldn’t grow here from the start. But no one listens to us old practitioners. You know everything better. If we’d planted turnips, they’d have grown.”

When the silos were opened in the spring, half of the fodder had rotted.

The LPG director was called. He cursed when he saw the damage, since a few collective members were nearby. “What a mess! How are we going to feed the livestock?” To himself, he thinks that lime would have helped a lot more. But the MTS agronomist might have discovered that . . .

“Plant more corn? Not a chance.” Binkowski now had his argument.

It seems sensible, at least to the collective farmers. In 1957, only two acres of corn are planted, the rest rye.

Erich Degenhardt, who is responsible for the livestock and their feed, knows that there won’t be enough labor to gather the turnip tops, but whatever is fine with Binkowski is fine with him.

He does nothing about the fact that the mower is sent out so late that no hay comes from 640 acres. 3200 decitons of hay, the planned feed for the winter, is lost.

Paul Flick meets Adolf Schlundt in Bremen.

There is good news from Zepkow. Reason to open a bottle of Dujardin.

“They lost a lot of livestock over the winter, the former Nazi local group leader smiles. But you know, Flick, we should get Degenhardt to do some more. There are still a few tricks . . .”

Erich Degenhardt gets some fresh orders. He should not have some cattle inseminated. That will make them useless.

“The big farmer thinks I’m stupid,” the livestock supervisor thinks. “That occurred to me a long time ago . . .”

But one could do it with the sows, too. Not enough hogs die.”

Erich Degenhardt has gone beyond his teachers in the Western Zones.

Degenhardt thinks the time to be ripe at the end of 1957. The brood sows are not brought to the boar any longer . . .

“If fit all works, the comrades will miss 500 young pigs in the spring,” he tells Heidemann. He laughs.

“Then they’ll have to empty their purse to buy some.” Flick’s son-in-law laughed at a joke gone well.

And Degenhardt had sick pigs taken to the vet too late. Sometimes they died first.

He didn’t have male piglets castrated, or he did it himself in a way that left them with hernias.

The collective farm lost 35,000 marks because it did not meet its contract. He excused it by saying: “Did we have the feed? Well, what could we do, then . . .”

Within twelve months, Erich Degenhardt delivered nine of his own fat pigs to market, and there were always enough fresh schnitzels and chops from his “own” production.

If Binkowski can do it, so can I,” he told himself. He managed to get fifty hundredweight of potatoes and some threshing from the LPG as well.

“A few more cents that the old man will never learn about.”

Paul Binkowski naturally is still doing his own business too. Like a shopkeeper, he’s hawking grain, harvesters, drilling machines, hay blowers and carts . . .

He feeds his livestock with the collective’s grain, over a hundred hundredweight in 1957 alone.

He must be paid for his work somehow, he says, if Flick doesn’t pay . . .

“This Degenhardt behaves like a Kulak in Scholochow’s Virgin Land under the Plow, maybe even worse, says Otto Rybaschewski, the LPG carpenter, and looks at the other comrades. I have heard he pays the colleagues in the milk plant whatever he wants to.

Karl Hiller frowns.

“What are you saying? He counted the money?”

“Yes, and he kept 25 marks for expenses,” adds Karl Rybaschewski.

“That too! — But Karl, do you have proof?” Otto Rybaschewski shakes his head.

“Anna Batschkowski supposedly said so — in the village. But nothing at the meeting.”

“Binkowski and Degenhardt know how to bribe. I think they’ve bribed our colleagues.”

“And what about Heidemann? I heard he recently railed against the LPG and the MTS in the pub.”

The party organization has had doubts for along time. The intrigues against party comrades, the increasingly frequent problems in the fields, the increasing livestock losses, the almost constantly drunk Binkowski, Degenhardt’s arrogant manner — this has bothered the comrades for a long time. They sense that the class enemy is somehow reaching into the LPG.

The comrades guess that Heidemann, Binkowski and Degenhardt are enemies of the LPG. But guesses are not enough.

There has to be proof.

“We will get the proof,” a comrade promises. “If things go in this way in Zepkow, the LPG will be bankrupt.”

Three private farmers want to join the Agricultural Production Cooperative. As Degenhardt learns of it, he says to his milkers: “What will we do with them? They won’t do us any good, only harm.”

He cleverly spreads rumors, and the membership meeting refuses to admit them.

In the village, he spreads the rumor that the farmers were dumb to want to give their good animals to the LPG for cheap money . . .

“I’ll tell you this, Binkowski, no new members. We already have enough smart alecs . . .”

“Agreed, Erich. If it were up to me, I’d do things differently . . .”

The glasses are emptying in the village pub. The barkeeper fills them again.

“There’s an LPG meeting tonight. Why aren’t you going?”, someone asks Lothar Binkowski.

“No interest.”

“And what will your father say,” mocks Max Boy.

“Don’t mentioned my father, Max, or . . .”

“OK, OK,” says Boy. “But I think it would be better for you to go, since two members of the SED are there.”

“They should grab a pitchfork rather than chatter about politics. Why are they going to the meeting?”

“I’m curious myself. But have another drink.”

Ten minutes later, Lothar Binkowski puts his cap on and leaves.

A few hours later, Captain Jürgens, head of the county office of the Ministry for State Security,” picks up the phone.

“Lieutenant Fetting, please. Comrade Lieutenant? Please come to my office immediately.”

As Lieutenant Fetting enters, the captain points to the desk.

“Read that, please.”

Fetting reads: “. . . Lothar Binkowski grabbed Comrade Walter Kulow of the SED district office Neubrandenburg and gave him serious head wound with an ashtray . . . he is the son of the LPG director . . .”

“The culprit has already been arrested,” Captain Jürgens explains, “but . . .”

“You don’t think Binkowski was acting on his own?”

“There are a whole series of issues at this LPG that lead one to conclude that the enemy is at work. In particular, the LPG board . . .”

A few hours later, the forester’s son Lieutenant Karl-Heinz Fetting and a young corporal are on their way to Zepkow.

Even the sturdiest jug breaks eventually . . .

Paul Binkowski is terrified as two members of the Ministry for State Security pay him an unexpected visit. The same happens with his assistant Degenhardt.

A few hours later, a pale Heinrich Heidemann listens and trembles as he hears:

“Your game is over, Heidemann.”

“They know everything,” he thinks.

It is 12 March 1958.

Experts determine that sabotage directed by the refugee fascist big farmers has cost the Agricultural Production Cooperative “Jupp Angenfort” over 580,000 DM. Degenhardt alone was responsible for the loss of 135 young beef cattle, 11 cows, 47 calves, 183 swine, and 72 sheep.

The enemy activity also did major ideological damage to the socialist transformation of agriculture.

Somewhere in the Western Zones, the big farmers get their heads together . . .

“The only one I feel sorry for is Heidemann,” complains Paul Flick.

“He is my daughter Else’s husband . . .”

“No feminine sentimentality, gentlemen,” interrupts Adolf Schlundt. “There’s always a risk. They won’t be hanged.”

“But they’ll get several years in prison . . .”

“Several years?” Schlundt shakes his head. He yells fanatically: “We’ll get them out. We’ll get them all out!”

“Don’t you understand? We’ll dispose of the whole Red swindle. Every man, woman, child and mouse! They’ll all be terrified of us.”

They were and are incorrigible.

The black vulture is still hanging on the wall of the federal building. It does not yet have the swastika in its claws [The eagle of West Germany].

Two murders sit in the ministerial seats. Those who are not yet murderers are planning it.

Three criminals face the district court in Neubrandenburg.

Heinrich Heidemann, HJ leader and SS man on call; Paul Binkowski, Stahlhelm member and S.A. hoodlum; Erich Degenhardt, Nazi activist, reserve member. Fascists yesterday, fascists today, the enemy of all peaceful labor.

The court sentences Heidemann and Binkowski to twelve years in prison, eleven years for Degenhardt.

As the criminals are led from the courtroom, the workers, tractor drivers and collective farmers stand like a wall. Against this wall, Flick, Schlundt, and their cohorts will break like brittle glass, as will the Oberländer, Lemmer and Strauß [West German politicians], glass the glassblower tosses in the trash.

Two long years have past, and the shadows have faded in Zepkow. Paul Kurz, an energetic and intelligent farmer, is the director of the Agricultural Production Cooperative “Jupp Angenfort.” He is one of the pioneers of socialist agriculture. He led the LPG in Kaeselin from 1952 to 1956, and gained much experience.

But what can a single man do? No matter how diligent and intelligent he may be, without the collective, without the aid and advice of the party organization, without the help of everyone in the collective, he could not make full use of his abilities. With that thought, Paul Kurz works for the collective farm and the farmers.

The state had to provide 157,000 DM of subventions to the LPG Zepkow in 1957. And today?

As drought hit the land in 1959, it did not detour around Zepkow. The opposite. The soil here is sandy and the meadows suck up water.

The grain became white. There was but 300 decitons of corn per hectare. Things did not grow. The fruit was thin or dried out. The paddocks turned brown.

The drought cost 60,000 DM! But what good would the will of the working people of the Zepkow collective farm be if they did not put their full energy into their work, into their future.

“We’ll have to make up in the stalls what we’ve lost in the fields,” the comrades in the party organization said.” “We must balance the books this year, no matter what!”

. . . from the stalls? But had not they suffered from the crimes of the counterrevolutionaries?

On 1 January 1958, the collective farmers had only 190 beef cattle and 93 milk cows — poorly fed, neglected animals. But now there are already 387 beef cattle in the renovated stalls. 141 milk cows, and 52 bulls are waiting for the butcher . . .

Instead of 263 half-starved swine that Erich Degenhardt had left, there were 471 fine animals — and that was at the beginning of December 1959! The number of breeding sows had almost doubled.

For the first time, the LPG has a feed reserve — despite the drought. The livestock brigade met the party organization’s expectations: By the end of November 1959, they had made up 400,000 DM. And there were still reserves.

The LPG Zepkow is now a going concern. Productivity is over seven marks per work unit. They’ve done it!

The private farmers have stopped saying: “We’ll never join that LPG.” Occasionally they knock on the collective’s door. Soon seven of the best joined up. Others founded an LPG of Type I, and all are members today. Zepkow is completely collectivized. All work in a socialist way for the good or our workers’ and farmers’ state.

The citizens of Zepkow now think differently. The age of the Flicks and Schlundts is gone forever.

The comrades say: “The class enemy has suffered two decisive defeats in Zepkow. The counterrevolutionary band was destroyed, and the LPG has developed tremendously since 13 March 1958. But we have no cause to be satisfied and lazy. We must remain alert, very alert! Zepkow has a great future, as long as we say alert!”

Last fall, as the potatoes were being harvested, the comrades from the Ministry for State Security came a second time — with two trucks. They came to help out with the harvest. The farmers were not surprised.

“They aren’t any different than us,” they said.” They are workers, farmers, tractor drivers, sons of farmers.”

. . . Zepkow has a great future.

The victory of socialism is not to be stopped, for it is the will of all those whom the historian Büdner in 1900 called cottagers, maids, and serfs, and all those whom the Schlundts mocked after 1945.

It is 1 January 1964. There are fireworks in Zepkow that brighten the night sky, coloring it red. The collective farmers are celebrating the early fulfillment of the Seven Year Plan . . .

The collective farmers are proud of their 930 beef cattle, their 1175 hogs, of which 450 are healthy mothers, their 4,000 chickens . . .

“Remember, Otto, that we had only 190 beef cattle in the narrow stalls of the big farmer in 1958?”

“And only 34 sow?”

“And the Kulaks thought we had too many . . .”

“They miscalculated; they didn’t take us into account!”

The sun is shining on Zepkow. Forever.

Last edited 13 September 2025

Page copyright © 2003 by Randall Bytwerk. No unauthorized reproduction. My e-mail address is available on the FAQ page.

Go to the German Propaganda Archive Home Page.