Background: The Nazi published a large number of 32-page booklets in a series titled “War Library of the German Youth.” They were intended to persuade the youth of the glories of war, and often included a pitch to enlist in the military. This is one of the last of the series, appearing in late fall 1942. The news on the Eastern Front then was not all that good. The campaign here described took place in 1941 during the initial German drive toward Leningrad.

The source: Dr. Alfred Thoss, Waffen-SS im Kampf vor Leningrad (Berlin: Steiniger-Verlage, no date, but late 1942). This is #151 in the series “Kriegsbücherei der deutschen Jugend.”

Forest, forest, nothing but forest! Pines, spruces, birches, and also alders when the ground is boggy. But this is not our kind of forest, where one can see between high, lovely tree trunks! The branches hang every which way, with thick underbrush beneath. You have to blaze your own trail, unable to see more than six feet ahead.

Scouting parties creep through this wilderness along narrow paths. But what good is their reconnaissance and exploration? It does not mean much in this vast wilderness. Who knows what is hiding in such mysterious terrain! There is, of course, no heavy artillery, which needs open areas, or at least small clearings. Machine guns also lack a field of fire and there is no room for tanks. But enemy marksmen have dug foxholes with openings no larger than a steel helmet, hard to see amidst the green moss. Further off the trenches are bigger, offering comfortable places to sit and storing huge amounts of munitions. Soviet marksmen can surprise one by suddenly appearing out of the thick jungle, or when they open fire from behind trees while wearing their green camouflage uniforms.

Scouting parties creep through this wilderness along narrow paths. But what good is their reconnaissance and exploration? It does not mean much in this vast wilderness. Who knows what is hiding in such mysterious terrain! There is, of course, no heavy artillery, which needs open areas, or at least small clearings. Machine guns also lack a field of fire and there is no room for tanks. But enemy marksmen have dug foxholes with openings no larger than a steel helmet, hard to see amidst the green moss. Further off the trenches are bigger, offering comfortable places to sit and storing huge amounts of munitions. Soviet marksmen can surprise one by suddenly appearing out of the thick jungle, or when they open fire from behind trees while wearing their green camouflage uniforms.

The SS men have been fighting in this jungle for weeks. There is hardly any variation in the terrain! Occasionally there is a field, sometimes cultivated, sometimes not, with wheat, sometimes even a herd of animals or a village with miserable, decaying huts. Those that are still standing are in wretched shape, but most have been burned down by retreating Soviet troops or by artillery bombardment.

Four kilometers further, the jungle turns into a swampy moor without trees, only a few bushes and tall, tough grass with small streams with brown water between. Mostly there is but a single path through such an area, and it must be fought for. As the enemy retreats, vehicles sink to their axles in the mud and the engineers have to build log roads to make a more or less firm path. This happened often, and whenever it rained the ways were so muddy that only heavy vehicles with tracks could bring munitions forward. No other vehicle could get through such a morass.

Even those on motorcycles could not find a usable route along the edge, and often cursed as their wheels stuck fast.

Vast and poor Soviet Russia! What does the soldier see there for days and weeks and months? Forest, always more forest, then a broad field of rye, beaten down to the right and left by vehicles and tanks, deserted and burned out villages, louse-infested and worn out people, and nothing more.

Here during the summer, things are green in every direction: the forests and fields, as long as they have not turned gray under the summer sun, the green uniforms of captured Soviet soldiers, the green horse wagons, stuck in the mud or shot up, the trucks, the artillery, the machine guns, the discarded steel helmets, the gas masks lying in the ditches. One’s eyes often see green and blue when enemy mortars and cannons fire, when one must either hold out or break through.

Soviet Russia is a green hell ! ! !

But the SS division succeeded, driving through this hell! The jungle is behind, open land ahead. Nothing could be worth than that jungle, everyone said. Everyone breathed easier. Also, of course, it was because Leningrad was nearer. This city had been their great and distant goal as they had fought the Bolshevist plague through the long deadly drive through Russia. They had now been outside it for weeks. The Russians had been in their element, constantly slowing our advance by treacherous bush warfare. They had not been able to stop us. “Nothing is impossible for the German soldier!” That is what the Führer said, and the brave German infantry — who bore the heaviest burden in these forest battles — continually proved it.

But now the munitions warehouses and weapon factories of Leningrad were much closer. The first large city in  the open terrain beyond the forest had been captured. A regiment from the SS division had entered the city from the west, while comrades from the army came in from the east. One knew that the Bolshevists had laid wide minefields to the south, so this area was avoided; the area could be cleared without casualties later. The regiment enjoyed a day’s rest. That felt good.

the open terrain beyond the forest had been captured. A regiment from the SS division had entered the city from the west, while comrades from the army came in from the east. One knew that the Bolshevists had laid wide minefields to the south, so this area was avoided; the area could be cleared without casualties later. The regiment enjoyed a day’s rest. That felt good.

Squad leader Arnold took his men through the city to search for weapons. One wanted to take a peaceful walk through the city that they had fought so hard for a few days before.

“Well, not much left,” said SS man Streit. “It would take a long time to find an unbroken window.”

“You’re always thinking about your own comfort,” joked squad leader Arnold. “You should be happy that we have a roof over our heads again; we had only the blue sky long enough, and it’s now getting to be fall.”

At the city’s main intersection, the soldiers had set a picture of Lenin. His outstretched arm pointed in the direction of Leningrad, and held a sign announcing “Leningrad: x kilometers.” Everyone passing by saw this peculiar sign. The SS men, too, stood around and laughed. The traffic was lively. Unending columns of German soldiers passed by, either on foot or on horseback.

The riders looked relaxed and at ease on the horses. The motorcycle riders looked relaxed and comfortable as well now that they were on paved roads rather than bumpy or muddy roads. Soldiers on bicycles rode past; their faces today were not covered with sweat and dirt sufficient to make them almost unrecognizable, as was often the case during the hot summer, but rather were clear, smooth and hard. They showed the hard exertions of weeks of war, but their eyes gleamed. They proclaimed confidence and victory. Victory! Victory! That’s what the rolling wheels also sang!

Tomorrow the SS men would move on, too, forward toward the enemy, but not as peacefully as here. Soon, they would sit down, then spread out! That is how it always was. Sometimes it was the order of a superior, sometimes enemy bullets. It always meant new action, new battle.

But not today. One stood by, listening and feeling the irresistible advance of victorious German troops, of which one was a small part. It flooded over each individual.

After a while, the SS men turned into a side street.

“I’m gonna look over there in the park,” said SS man Körner, who was teased because of his accent, but was widely liked because he was always helpful and knew how to do just about anything. Above all, he was an excellent cook, which is why the unit had long envied Arnold’s squad for having such a valuable man. Whenever there was time, Körner managed to find chickens, sometimes even geese. That was in fact forbidden, but whenever he was caught Körner managed to talk his way out of it by saying that he had found the bird almost dead alongside the road, and “seriously injured animals” could be “released” from their misery. Sometimes, others took over Körner’s duties do that he could transform his booty into edible condition. The bird was brown and crisp, and there were a lot of onions. Along with roasted potatoes, it did not taste bad at all. But things tasted good not only because of the onions. Rumor had it that Körner prepared the best roasted potatoes. That was no small matter. In Soviet Russia where there was nothing for miles, roasting potatoes was a fine art. Many had become roasted potato specialists.

As Körner’s suggestion showed, he was not only a learned Saxon, but a bright one as well. He told his comrades about old tsarist palaces and parks, the comforts they concealed, and what sorts of love affairs, horrors, and treasonous activity had gone on there.

They were in the middle of the park, following an attractive path along a lake with a lovely view, overlooking a large palace. Early yesterday, things had looked different. At the other end of the park, there had been mortars and heavy tanks. Now one sat quietly on a bench and looked over a wide lawn and high oaks with thick trunks. They really were oaks, just like at home.

The next city to be taken, Körner said, had a similar palace and park. It was only 30 kilometers away, but since it was very close to Leningrad it would surely be stubbornly defended, and one would have to see how long it would be before one could sit there was one was sitting here.

We will learn that the conquest did not take very long, but that one could not sit as quietly as one could in the park here, because the Bolshevists fired on the with heavy artillery, naval guns from Leningrad’s harbor, and planes. Things were not that far along yet, however.

As the SS men slept this evening, some dreamed of the coming battle, others of adventures in the many rooms of tsarist palaces.

The next day, all the evidence showed that one was reaching an important center of the Bolshevist empire. During the long battles in the forests, there were only bad roads, but here, to the north of the city, the main highway had three broad lanes leading further to the north. Two of them were even paved, and in perfect condition. The supply corps would certainly be delighted!

The regiment of our comrades from yesterday marched to the right and left of the right lane. The battalions and companies were now spread out, passing the division’s artillery company that had set up here to guard and protect the right flank from enemy attacks.

The fifth company, to which squad leader Arnold and his men belong, was still protected by a rise stretching diagonally before them. The closer one came to it, the greater the signs of the hard battle that the defenders had given the attacking SS men of the first battalion. They were to be relieved this morning by the second battalion. As one advanced across the field, one kept finding well-hidden foxholes with excellent firing positions. In the gradually rising ground — difficult to see because of their excellent concealment — were many strong, now destroyed, bunkers. They were protected first by a layer of thick tree trunks, then a layer of earth and sand, then more tree trunks covered by dirt and sod, making the bunkers impossible to distinguish from the surrounding terrain. There were openings only in the front, protected by thick tree trunks to the side, from which hellish fire could be directed against attackers — until a direct hit by an anti-tank gun either killed those inside or drove them out.

One could see that the Bolshevists had to pay dearly for their resistance. Their bodies were strewn about the field; destroyed or deserted machine guns with their thick shielding, left behind mortars in shallow holes. On the road, there are green trucks, green artillery, and even a green tank apparently left to defend the retreat, but victims of German artillery fire.

“We’ve got some work left to do,” said company leader SS Untersturmführer Hertel to his men. “They probably aren’t going to let us stroll into Leningrad.”

Distant artillery fire reminds one that here, as everywhere in the Soviet Union, one can’t speak of German soldiers talking a pleasant walk. They always have to march a little further, several kilometers further on there is always another hill. The company’s units were spread out, and even those units were spread out because of the danger of enemy air attacks. Although our fighters controlled the air and thick squadrons of bombers and dive bombers headed toward Leningrad, Kronstadt, and other Bolshevist strongholds when the weather permitted, enemy Ratas or even an occasional bomber dared to fly over the conquered areas, and then one had to watch out lest one by hit by a lucky bomb.

That evening the company relieved the comrades in the front line.

The ground was flat and open, with only a low fir forest direct ahead. One had to walk bent over through the trenches; as soon as a steel helmet poked above, enemy machine guns or anti-tank guns opened fire. To the left of the forest was a heavily defended village that protected the route to the big city to the south. It was to be attacked and taken tomorrow. Several scouting parties had to be sent out overnight to explore the ground and find out something about enemy forces.

Squad leader Arnold undertook one such mission with Streit, Körner, and Fischer.

Squad leader Arnold undertook one such mission with Streit, Körner, and Fischer.

The night was bright and starry as he and his men left the trench. Ahead were a few hundred meters of potato fields, then the road that ran right to left through the area. We had several listening posts in the trench. They had heard nothing of the enemy, except from the village further to the left, where dog barks could be heard throughout the night, suggesting that something was going on. The men they had relieved said that, during the day, the Bolshevists had fired on them with rifles and anti-tank guns. Our dive bombers had dropped a lot during the day, so the Soviets must be well dug in. Arnold’s platoon was to get to the village unseen, carefully scouting out both the terrain and enemy positions.

“Keep an eye on us as best you can,” Arnold told the listening post. Then a handshake: “Good luck!”

The men went along the deep ditch next to the road. Then they reached an intersection. One road led directly to the village. It was the shortest way, the quickest way to reach the village. But the moon was too bright on the road and the ditch, and besides it was too obvious a route to follow if one did not want to be seen; one could shoot only in case of necessity.

Therefore, more to the left. There was a small hedge of birches and thorn bushes that offered good protection, but might also conceal enemy positions.

Well, nothing is certain in war, at least for scouting parties. Crawl across the field to the first bushes, behind which one could continue stooped over.

Arnold gave a gesture, and everyone dropped quietly to the ground. He waved Streit and Körner up to him; there, to the right, was a strong enemy post. The Soviets were standing in front of a barn, several hundred meters outside the rest of the buildings of the village. It looked like a normal, wretched barn with holes in the roof, but there was a surprising amount of traffic going in and out.

Was it a concealed bunker? It would not be the first time that a harmless building suddenly turned out to be a strong defensive position.

Again and again Arnold turned his binoculars toward it, and also let Körner have a look. Their suspicions increased. But they could not be certain. They had to carefully go around the dangerous position. In the village, one could hear automobiles. Were they bringing reinforcements or munitions? That was important to know. It was easy to advance through the potato field. The SS men crept around the enemy barn to their right.

Between the potato field and the first buildings in the village, there was a road with small gardens. After that, a piece of open ground. It was dangerous, of course, to cross it, but squad leader Arnold wanted to attempt it in order to get a look at the village! He only took Körner along, leaving the other two behind.

“We’ll be back soon,” he said. “If anything happens in the village and we can’t get out, get back as fast as you can.”

Two shapes crept to the nearest garden. The dogs in the yards did not bark any more than they had before. There were footsteps from the road, but they faded into the silence. The two who had been left behind, Streit and Fischer, thought about their comrades who were now in the enemy’s midst; any second they might be discovered, each second might bring them martyrdom, torture, and death. When was it that they had found a captured scouting party back then in the forest? Three weeks ago.

The four comrades lay under a pile of spruce and birch branches. They had been shot to pieces, their corpses showing many bullet wounds. Their ears and noses had been mutilated.

Nothing unusual was going on in the village. Their comrades must either not be too far ahead, and were still watching, or they had gotten into the village without being seen by the enemy. The latter was the case. Arnold and Körner had gotten to the garden, and could work forward from their under cover. Most of the Bolshevists seemed to be relaxing in the buildings. The only ones on the street were the crews of the anti-tank guns.

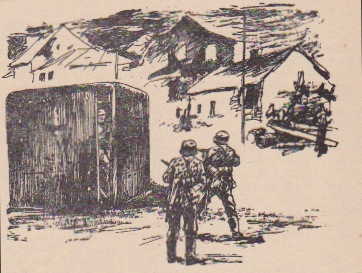

In the center of the village, where a street went left from the main road, there was a strange, square-shaped black structure at an intersection, completely visible and in the middle of the street. Could it be a bunker? No doubt about it! After long observation, one saw a square opening in the wall, a slight movement, and a gun barrel protruded. Apparently there were people inside. This was an important discovery! Wagons and trucks were parked along the narrow street. There had to be strong forces in the village if there were vehicles! The guards marching back and forth kept the two SS men from getting any nearer. But they had seen enough.

The ones left behind were delighted as their comrades finally came back through the darkness. The return was as slow as the advance had been, but they moved a little more easily and freely, since everything was behind them, and their front ahead. The company commander was happy with the results of the scouting party, and passed the news immediately on to the battalion. commander, who that same night got reports from other scouting parties in the area. Several changes were made in the attack plan for the morning, and the artillery battalions received orders to concentrate their fire in particular places. Given the quiet on the enemy side, a night attack was unlikely; the reinforced posts were withdrawn in order to give the men time to sleep before the attack that would begin in a few hours.

A milky haze covered the ground as the artillery began to fire that morning. At almost the same time, the infantry took up their final positions. The attacks toward the north were readied on all fronts.

Fortunately, the enemy artillery responding to German fire passed over the front trenches, and the fifth company, concealed from the enemy by the fog, was able to use the road that last night’s scouting party had discovered. Squad leader Arnold and his men were at the front, along with the company commander. One of the company units was crossing the potato field to the left to reach the village, but the main enemy resistance was to be expected along the main highway. The anti-tank guns that had protected the highway overnight were moved forward, for in the past the Soviets had always brought in their tanks when things got lively.

Sturmmann Körner and Fisher were at the lead. Was anything going on in the barn?

“Maybe they’ll invite us to coffee and the commissar will give us ham and eggs,” Körner said to his comrades.

The Bolshevists provided a somewhat different reception.

To the left where the second platoon was a little ahead, wild firing from machine guns and rifles broke out. Now things broke loose along the highway as well. Shells hissed overhead, surely from anti-tank guns. Shells started exploding sooner after being fired; the artillery had to be nearby. The barn was certainly a concealed bunker. The infantry were quickly ordered to hold back until a few shells could hit. The anti-tank guns were also used. Shot after shot hit the enemy defenses, which replied with strong fire. Meanwhile, the infantry were doing their best to advance toward the village to the right and left.

But things were not going well. The Bolshevists were firing like devils with mortars and machine guns from buildings and field positions. The mortars were the worst. They came in and exploded before one had much warning. One had to return enemy fire from whatever cover could be found. The main resistance still came from the bunker, although its structure was now covered in heavy flames. It had to be kept under heavy fire. Fortunately, the ditch alongside the road was deep enough that several men could creep nearer to it and fire a flare. The infantry and anti-tank guns ceased fire, and in a few steps the men were at the bunker. Two batches of hand grenades through the slit, and the place was smoked out.

There was a powerful explosion toward the front. Through the resulting gap, two groups of the fifth company headed toward the village. They had to run to the first building before they could take a breather. Arnold and his men, along with the company chief, were among the first to reach the protection of a building entrance. Several comrades, Streit among them, had fallen along the way.

They quickly set up a machine gun position at a corner of the building, in order better to fire on enemy positions they could see! That helped the comrades on the right side of the potato field, who could not work their way to the village more easily. The Soviets continued to fire wildly. One had to wait until the second unit of the company arrived from the left. Two anti-tank guns were brought into the village. About 800 meters ahead was the steel bunker discovered yesterday at the intersection. It would be a tough nut to crack.

While the SS men dug in behind the first building, there was a rattling sound. Strange! There were no trucks coming from our side, yet the sound came from a heavy vehicle.

It had to be an enemy tank.

One anti-tank gun was near the men in the ditch, covered in front and protected by a wide pile of dirt which had a path to the building. The other was on the far side of the street, protected by two large trees. They had been no time for concealment, other than a few green branches.

Rumble! The enemy tank was already there. The filthy thing kept shooting, but it was aiming too high. Our gunners hid exhausted behind their weapon. They had to remain exposed to the enemy, since the street rose gradually and steadily toward the village behind them. A damned tough position.

The tank rolled on, proudly and confidently. It must have been a 32-tonner. Now it was only three hundred meters distant, and the beast kept coming. Our anti-tank guns did not seem to bother it much at the moment, but its shots were landing all too close to our forward anti-tank gun!

Meanwhile, a group of SS men had worked their way forward to the next building, despite enemy fire. Two prepared charges to throw under the treads of the monster when it got close enough. Arnold’s squad stayed near the anti-tank gunners, covering themselves behind the building. One man had already been hit by a heavy mortar fragment. Fischer sprang forward to pass on munitions.

There! A powerful hit! An explosion, dust in the air! A direct hit on our anti-tank gun!

“Damn” said company commander Hertel, the first to recover. “Arnold?” “Here.” — “Körner?” “Here.” The remaining men came together; other than the shock, nothing had happened to them.

“Ready hand grenades! They can’t get through!” the Untersturmführer shouted to his men.

Everything was overshadowed by the duel between the tank and our second anti-tank gun. Machine gun bursts and rifle shots could also be heard. To the right, comrades from the other unit were moving into the village. That did not seem good to the tank and the Soviet riflemen following behind. It turned suddenly and went back the way it had come. Unfortunately, the shots of our brave anti-tank gunners had had no effect. Further firing seemed useless, but suddenly the tank stopped, made several turns, pulled to the side, and stopped entirely, facing us broadsides. A final shot had ruined the tread! But this success came at a high cost: we had a fair number of wounded. They were quickly cared for while the battle for the village continued.

The nearby buildings were stubbornly defended by the Bolshevists. As our men broke down the first door, seven Bolshevists came out with their hands high.

There were still shots coming from the next building. A few hand grenades flew inside: noise and splinters, then flames were reaching the roof.

Meanwhile, the anti-tank gun was moved inconspicuously along a brook adjacent to the garden, closer to the square steel bunker at the intersection. The bunker was firing in the other direction, where German attackers were approaching. The well-aimed fire thus caught it by surprise. But at first, it seemed impregnable. Shot after shot hit it, until a small slit was closed from the inside. Those inside had noticed something, if not the anti-tank gun, the machine gun. The gun moved closer. The gunner targeted the firing slit of the steel enemy, without firing immediately. We can wait, the gunner thought.

Without the support of heavy enemy weapons, the village was quickly in our hands. There were individual shots here and there, but they, too, soon stopped. Prisoners were collected on the street. In all, there were 120. Many had been killed during the stubborn defense, and others had retreated to a small piece of forest outside the village.

The company chief stood around the square-shaped steel bunker with Untersturmführer Hertel, squad leader Arnold, and the other men. The bunker was not very big. No door was visible.

“They have to get in there somehow,” the company commander said. “The Soviets are still hiding in there! We  can’t leave it there. They have to get out!” — But how?

can’t leave it there. They have to get out!” — But how?

They knocked, first with fists, then with gun barrels, then two men took a big stone and banked it rhythmically against the colossus. Nothing happened.

“Let ‘em starve,” said the Hauptsturmführer, and left with his men, but then sent three men back to watch for any movement of the gun slit, and to keep careful watch on the bunker.

Körner, meanwhile, had gone back to look after comrade Fischer, who had been passing munitions before the tank shell hit. Fortunately, he had been to the side, and his injuries were not as severe as the others. “I’ll be back tomorrow. A little arm wound like this isn’t going to keep me from Leningrad,” he had said. Well, one would have to wait and see. The company was now moving toward the forest. The underbrush was not thick. One could see between the trees to the other side. Our artillery shots hissed through the air above the SS men. Their targets were a few kilometers further, probably the airfield, its hangers, and barracks. According to the map, it was a big airfield. From the other side of the forest, it and the edges of the next city should be visible. The city was the last major position before Leningrad, and would surely be heavily defended.

A shot rang out behind them. Instantly, everyone ducked behind trees. Where had it come from? They’d searched every building. Was there some sort of concealed position with a sharpshooter? Everyone listened, but no one heard anything.

Someone came running up. It was one of those who had been left to guard the mysterious and silent steel bunker.

“Where is the company commander?” — “Over there in the clearing.”

The courier hurried over.

“We have them!” — “Who?” — “The bunker crew.” — “Captured?” — “Dead.”

“How did that happen?” The man reported: “For a long time they didn’t do anything inside. We didn’t do anything either and kept still. Apparently they thought things were clear and that we had fallen for their trick. Slowly, centimeter by centimeter, one side opened. A few fingers, a hand, a head, then a hand with a pistol appeared. The Bolshevist suddenly saw the two of us. We opened fire. He couldn’t get back inside. What to do? He couldn’t get back inside. Instead of surrendering, he started shooting. He hit my comrade in the leg. But that was the end of him. There were two dead Bolshevists inside. Apparently, a machine gun burst got them through the opening.”

“What’s the crate look like inside?” the company commander asked. “No wonder we couldn’t get through! The thing had steel walls at least nine centimeters thick. Put such a fortress in the middle of the road and one will feel safe inside.”

Well, that was finished. There was no danger from the rear any longer. But there was also no time to worry about what was behind, since the front demanded full attention. The Soviets seemed to have pulled back further, for their artillery shells were landing at the edge of the woods.

“They don’t want us to get out of the woods,” Arnold said. “What shall we do?” “Wait for orders,” said the platoon leader.

The battalion commander had heard how hard the battle had been from all the companies. Aerial reconnaissance and artillery spotters had also noted strong enemy artillery positions. The regimental commander, therefore, decided against further infantry attacks for the day. The artillery would weaken enemy positions at the edge of the city during the afternoon and tomorrow morning before the attack.

So, for today, dig in. Hold the position! Things will continue tomorrow.

“Nothing until morning,” Arnold told his men. “And we were making such good progress today. Now we have to watch out to be sure nobody messes things up.”

Everyone began to energetically dig foxholes that would be safe from shell fragments.

“No one did that as well or as quickly back home,” thought the company commander. “Here in Soviet Russia they all get to work right away. One learns a lot from this kind of war.”

Most dug in toward the back of the woods. Only a few reinforced positions were established at the edge of the woods. Saying edge was really saying too much. There was open ground only to the right. To the left, the woods ran into a park that surely belonged to the palace the city was supposed to have.

Here, too, there were large, beautiful oaks. A wide stream wound between them. To the right, the terrain rose a bit, then dropped down toward the city into a broad depression along the edge of the city.

From the rise, one could look over the city to the north.

Late on the clear afternoon, Untersturmführer Hertel and squad leader Arnold went up there. What was that in the distance? With binoculars, one could see the shape of a huge city on the horizon.

That must be Leningrad.

Leningrad! Before that Petrograd, and earlier still St. Petersburg! One had gotten so close to the enemy that one could look into his stony heart! Great joy broke out! One was part of it! One of the first to see it.

They looked for a long time. Then they went back to their men and told them what they had seen. Everyone was filled with enthusiasm. Sturmmann Körner knew that in the past, Russia had not reached as far as the Baltic Sea. Tsar Peter the Great had conquered the land, then sunk pillars into the soil along the river to build this city “If only those back home knew that I’m up here by Leningrad,” one said, and many thought the same.

Dinner tasted particularly good. The SS men did not let the heavy enemy artillery fire disturb them. One was used to it. It was, however, a very noisy night.

The front posts were strengthened, and the evening artillery fire was not as scattered as usual. Just before midnight, everyone was torn from his sleep. The Soviets made a night attack. They crept up like little bushes and attacked from the spruce forest to the left, each with a little bundle of spruce branches tied to his back. The sentries had spotted the cleverly concealed enemy in good time, but they came in strong force and in waves until they were in hand grenade range. As the dull hand grenades explosions resounded, the sentries readied their bayonets. The machine guns hammered mercilessly at the advancing Bolshevists, pitilessly cutting down many; one could hear their cries between the shots. On our side, too, several comrades fell who would have been happy to storm the last bulwark of the enemy city tomorrow morning. They lay now cold and motionless, or had to be carried back to the first aid station. When the nocturnal battle was over, the tired soldiers could stretch out again, if only for a few hours. They knew well enough that there would be a hard battle tomorrow.

The SS men were not surprised when, early in the morning, lively artillery fire began from our artillery and the enemy’s, much different than what was usual in the morning and evening. Each calmly prepared, ate breakfast, drank coffee, and smoked a cigarette.

“It will come soon enough. Why get excited?” That was the motto of these old soldiers. Old? What does that really mean? What counted here were the battles, the scouting missions, the attacks that one had been part of. Otherwise, everyone was equal, whether he was nineteen or thirty.

“Well, what do you think, will we succeed today?” said squad leader Arnold to Körner. Then, in surprise: “Fischer, you’re back already? I thought you’d already be back in Germany after that wound. Did they release you, and do you know what you’re doing?” — ““Yes,” he answered. “I didn’t want to go back right away. I asked the doctor, pleased with him, to let me come along at least to the city today, and he said OK. The army injury isn’t all that bad.” “You’re a real man,” said Arnold as he patted him on the shoulder. “ “Nice of you not to leave us in the lurch.”

The attack was planned for 9 a.m. Late, but we can wait, many thought. Some good things have to happen first. They were the divebombers. Now that it was fall, there was too much early mist. They could fly only after visibility improved, when they could lay their eggs to good effect.

That’s how it was today. There were howls and rumblings as the big birds rose into the air. The howls the divebombers made as they plunged down were always new and exciting for their friends, terrifying for the enemy. Their climbs and dives looked light and easy, as if these big planes were only balls in the air, but woe to those who were at the receiving end of their bombs! And today there were incendiaries! Earth flew high into the air, thick black smoke rose in clouds. “We can use that. We’ll finish what they start,” said the company commander to his men.

Then the time came.

The attack began. The first weak Bolshevist positions were overrun. Soon, one was in the bright, open oak forest for the park. Shots from the enemy whizzed from all sides. The enemy had built strong earthen fortifications in the rolling terrain. The many watercourses were linked with barbed wire along their swampy banks. At least the tree trunks were thick. They always provided a little cover. If only there weren’t all those ricochets in every direction. Under these condition, one at first gained little ground. The engineers first had to smoke out the strongest enemy defensive positions. That happened. After a number of strong wooden bunkers had been destroyed after hard, close quarters combat, the infantry advanced through the park along a broad front.

The enemy had apparently lost his communications. Things like this happened: the battalion commander, his  couriers, and several men from the intelligence staff were walking along a wide street behind our lines. Suddenly they heard a rattling; they listened. Could it be — no, was it possible? It was possible! A heavy Soviet tank came slowly down the street, its gun threatening the vicinity. They dove into the ditch and found a few bushes to conceal themselves. The tank had not seen them. It slowly rumbled along.

couriers, and several men from the intelligence staff were walking along a wide street behind our lines. Suddenly they heard a rattling; they listened. Could it be — no, was it possible? It was possible! A heavy Soviet tank came slowly down the street, its gun threatening the vicinity. They dove into the ditch and found a few bushes to conceal themselves. The tank had not seen them. It slowly rumbled along.

“Well, children, we don’t have enough hand grenades to blow the treads off this beast, “the Sturmbannführer said. “Keep quiet.”

He did not have to say that. The eight men were as quiet as mice as they hid in the ditch. The monster came closer. What would happen? No one know, each hoped only to remain unseen. Now the steel giant was only a few meters away. One could see the tread turning, watch the turret swing a few centimeters right, then left. Their hearts pounded for a few seconds. Now it was past. Would it keep going? Gunfire ahead? Didn’t they hear it? It would be so easy to run up behind it! A damn shame that they did not have enough hand grenades. Now it was further away.

What to do? Stay in their dangerous position? The tank only needed to head toward their side of the ditch and send a few machine gun salvos their way to finish them off.

“Stay still!” the company commander ordered.

One did not know if the tank might be made nervous by the silence in the area, or the firing behind us, and suddenly turn around, in which case it would certainly see the fleeing men. And that’s what happened! It went about 30 meters further down the street, then stopped, probably to listen, then came back at the same slow speed.

Once again, things were tense. Had it discovered us? No one said it out loud. The men hugged the ground. Who could believe it? It went past again, but in the opposite direction.

“That can only happen once,” someone said as the evil enemy disappeared. Something similar happened elsewhere on the battlefield. The airfield and hangers were captured that morning; the German infantry were already beyond them. Around noon, an enemy medium tank rolled into the middle of the airfield, turned around, rammed a Soviet truck, and stood still, directly in the line of fire for the German anti-tank gun that was in a conquered enemy earthen position. It took the insolent arrival under fire. Quickly it punched a hole in the tank. The hatch opened slowly and a Bolshevist climbed out. When he saw he was surrounded by German soldiers, he started firing wildly in every direction. Not the way to behave! It was insanity and cost him his life!

Late in the afternoon, the SS men reached the edge of the city from the southwest. From the south, their fellow battalion from the division had arrived, and comrades from the Wehrmacht had reached the goal from the east. Enemy artillery kept trying to disrupt German communications, sometimes firing intensely at particular targets. The mortars were at the city’s edge, where the Bolshevists expected the German attack. There had to be tanks in there, too, the anti-tank gunners had discovered, who were at the front of the column on the street leading into the city.

“Take enough hand grenades along,” said the platoon leader, Untersturmführer Hertel, to his men. Arnold’s group had already thought of that. They had often learned that one of these little things could save their lives. They attached them to their boots and belts.

It was late when the attack was ordered. The enemy artillery fire had died down. Perhaps they did not think the Germans would attack any more. But they were wrong.

Squad leader Arnold and his men advanced along a little stream. The first buildings, which had been reduced to ruins by our artillery over the past few days, were searched with bayonets ready. No one was left. They stopped as they reached a wide street that went left.

On the other side of the street was a long facade of a once very large building, whose thick walls had suffered a lot. There was a front yard with high, thick bushes that blocked the view of the ground floor did not seem too worrisome. But something big and green moved. Damn! It was a tank. The road left to the left into the park, where our anti-tank guns were located. Hopefully, the lads were alert!

The tank moved slowly, without making much noise on the soft ground, since the motor was almost drowned out by the noise of the battle. It went behind the greenery, the turned suddenly onto the street toward the direction of our anti-tank guns. It fired a few shots, and was fired at, then turned back and cleverly concealed itself in the greenery.

“Prepare the charges,” Arnold said to his men. When he comes out again, We’ll throw the things under the treads.”

They kept quiet. Waiting was hard. One could hear gunshots to the right and left, even ahead of them. Several buildings into which hand grenades had been thrown to chase out the Bolshevists were in flames.

Now the green armored monster, as cautiously as before, left its cover to head toward our anti-tank guns, and started firing.

At it! The charges were already under its treads. A terrible explosion, and dark smoke filled the street. The monster tried to get away, but the tread did not let it. Look, two men climb out with white cloth in hand. Squad leader Arnold and Untersturmführer Körner approached them cautiously. They apparently had no desire to keep fighting; they had left their weapons in the tank, where a third man lay seriously wounded. They headed back to the collection point for prisoners of war.

At it! The charges were already under its treads. A terrible explosion, and dark smoke filled the street. The monster tried to get away, but the tread did not let it. Look, two men climb out with white cloth in hand. Squad leader Arnold and Untersturmführer Körner approached them cautiously. They apparently had no desire to keep fighting; they had left their weapons in the tank, where a third man lay seriously wounded. They headed back to the collection point for prisoners of war.

The anti-tank gunners had rather long faces as they had to grant the infantry’s success. But then they took up the hunt together with them again. They moved their guns to the next street corner, while the infantry went through the building ruins, then back to the street, where other comrades were hurrying from cover to cover to render harmless the few Bolshevists still left who were firing from the buildings or rooftops. The enemy resistance was not particularly heavy; the German attack had apparently been unexpected. A unit of the first company had passed straight through the center of the city to its northern edge, where it discovered Soviet machine gunners smoking comfortably next to their weapons. They took them prisoner by surprise. This unit was followed by a larger detachment of SS men. They went further into the ground around the city and prepared to defend against the expected Soviet counterattack. The systematic cleaning up within the city continued. Those Bolshevists still fighting were soon taken care of and taken prisoner. Men of military age hiding with civilians in basements were taken to a camp behind the lines. There was good reason for this cautionary measure; those guys hiding with women and children in often hard to reach basements were not entirely trustworthy.

How easily a Soviet soldier in civilian dress could turn out to be a partisan, arsonists, or looter!

The fifth company was stationed at the northern exist to the city, where a highway headed directly toward Leningrad. The men would have liked to keep marching, since only light enemy rearguard forces were visible. However, the conquered position must first be secured. German forces along the front line were not all that strong, and there were only thin lines within the city. There were bicycles and vehicles on a few streets, but they were men from the communications section of the intelligence division, which had to repair damage to the rapidly laid communication lines to the battalion as fast as they were torn up by enemy fire, or transports with munitions and food for the front.

Arnold’s group had come through the attack on the city well. No one was missing as they received orders to take up defensive positions. These positions were on an embankment that had probably once been for railroad tracks. Today, there were no remaining traces of the tracks. A bit to the right, it made a sharp curve to the left. It was rather odd that here, the German defenders of Arnold’s squad were on the right of the embankment, but over there they were on the left side, since the right side had not yet been cleared of enemy forces. As they retreated, the Soviets left strong wooden bunkers that the SS men took over. It was warm inside, and one was reasonable secure against enemy artillery fire. Several miserable little buildings stood about twenty meters from the embankment Most had been destroyed; dying flames from the others.

SS men Körner and Fischer searched through what was left. What a surprise they had as they entered the third one! They met a woman who greeted them with “Grüß Gott!” Germans here? Unbelievable! “Come on in,” the woman said. “I’m German. Just this afternoon three Soviet soldiers sat at my table and wondered whether it would be better to stay here and surrender; apparently, they said, they’d be dead and buried in a few days. But then they left — and I knew you’d be coming.”

“But weren’t you worried, and aren’t you afraid now? The Soviets are certainly going to send some heavy stuff our way,” one asked.

“Well, if you’re here, I can probably stay. I don’t have anyone left,” she replied. “First, I don’t know where I’d go, and second, the Soviets will steal everything if I am no longer here. You can’t trust anyone here. Everyone is poor, no one has anything, and they take whatever they can get.”

What an astonishing experience to meet a German woman after so long on enemy soil, in the face of the enemy!

As they entered the room, they immediately saw that German order prevailed here. There was a sofa, and pictures of the family on the wall. A sewing machine stood to the right of a window, and there were lovely flowers in the window box. The table had real chairs, and there was a comfortable easy chair. Astonished, the SS men surveyed it all. One sat down on the sofa near the window.

“That’s where my son and I always sat,” said the woman.

“Is he here,” Fischer asked?

“No, they took him away.”

“You’ll have to tell us everything when we come back. Now we need to look after our comrades.”

“Why are you happy? Found something to requisition?” squad leader Arnold asked.

“No, but we made a wonderful discovery: We found a German mother here!” was the answer. “She lives in the house over there.” The men told their squad leader about it, and soon he knew everything.

The woman had numerous visitors the next day. Everyone wanted to see her, and they all felt at home in the little house, in the middle of other deserted ones, surrounded by artillery fire. The company chief soon learned that a German lived there. Tomorrow was comrade Fischer’s 19th birthday; they decided to celebrate in this house if the enemy left time for it. But no one knew if it would be possible.

There was a peculiar silence the day after the city had been taken. The enemy apparently had to recover from the surprise. The SS men had several contacts with scouting parties the second day in the area around the city. The terrain beyond the embankment was unpleasant. There was a heavily fortified village that stretched for a kilometer along the highway. It was to be attacked from both ends simultaneously once our troops on the left flank had advanced further.

The enemy sent terrible artillery fire the second evening. They were heavy weapons, 21-centimeter artillery guns, along with heavy naval guns firing from the Gulf of Finland. Then there were the heavy mortars the enemy often used. It was hard on those transporting food and munitions, who had to pass through the barrage, while the infantry, except those on sentry duty, could take cover in strong bunkers.

Our artillery replied to the enemy. An observation post was established on a high tower in the city, from which one could see far into enemy territory. One could see Soviet quarters, truck convoys bringing supplies, trains, and other good targets that could be taken under effective fire.

Divebombers in large numbers often headed toward Leningrad and Kronstadt during the mornings of these clear fall days, sometimes in the afternoons as well. Sometimes, the infantry counted thirty, forty, even fifty at a time.

Wednesday was to be Fischer’s birthday party. Tuesday evening, the artillery fire was so strong that the company chief, who was in the area, ordered that the woman be taken from her house and taken to a safe bunker. The explosions were dangerously near the little wooden house.

She gave in to the young men only reluctantly, some of whom she had gotten to know better. During the short trip from her house to the bunker, she saw the sentries, several of whom were behind machine guns. She didn’t think the poor lads should be up there, either. “Ah, they’re safe,” someone said. Well, she’d seen enough wounded and dead Bolshevists. She knew what was up.

They sat in a large, spacious bunker, the company commander, squad leader Arnold, and his six men. The Bolshevists were real voles. They knew how to dig and had probably built it expecting to stay a long time.

Someone asked the woman if she had seen the Soviets building the bunker alongside the embankment

Certainly. Women had helped to; they above all had to dig the deep anti-tank ditches. Her daughter had been drafted for this in August and she had not heard anything from her since.

Now the woman began to speak of her life. She sat on a wood bed, elbows on her knees, her wrinkled hands folded. Quietly, humbly, her wrinkled face looked out at them. She spoke.

“We are actually Germans from Volhynia. During the last war, the rumor was that the tsar was going to send all the Germans from our area to Siberia, which actually happened in 1915, so my husband and I moved first to Livonia, and when the war came there, to here. We lost almost everything we had, and were able to buy only that little house and small piece of land. Everything got difficult when the revolution broke out. There wasn’t anything to eat, and my husband, who worked in the factory, hardly earned anything. Not much has changed since then! We were in bad shape, even through we always worked hard. Our two children were born here, a boy and a girl. We always worked so that they could have it better. But it didn’t turn out that way. After a house search in 1936 that didn’t find anything, our son was arrested and imprisoned. Although he was released after two years in Archangel, he could not come home, but had to work in that distant city. Two years later, my husband was arrested and hauled off. I never heard from him again.

So now I was along with my grown daughter, and we both had to work hard to meet production requirements and pay taxes. Last year, taxes were so high that we had to sell a cow. This year, it probably would have been our little house. And now there is war, and who knows where my daughter is. Maybe she’s dead, and I’m all alone.”

That was the woman’s story.

Many of the young SS men had heard of the large recent settlements of ethnic Germans from former Poland, the Baltics, and Bessarabia. They probably also knew that many ethnic Germans had been resettled from the Ukraine and Caucasus to Siberia, and that Stalin had ordered that the Volga Germans were all to be resettled in Siberia, which had certainly resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands. But they had not known that Germans lived up here, too, at the gates of Leningrad. This family’s fate moved them deeply. How good their loved ones had it back home, protected by the Reich and the great people’s community, not knowing the poverty and dangers that Germans abroad suffered. Each determined to be even more friendly to this German mother, who was treating the soldiers as her own sons even though her fate had been far harder than theirs. Meanwhile, the howls of shells and the explosions continued outside. Sometimes they were so close that even the strong bunker shook. In between, one heard machine gun and rifle fire, sometimes closer, sometimes further.

But all the enemy’s attacks were repelled by the alert sentries who stopped every attempt to break through.

The heaving firing slowed only after midnight. The woman went back home. The next day was calmer. Still, the Bolshevists fired their artillery and mortars occasionally, so one had to be cautious. During the night and early morning, several big scouting parties were repelled from strong positions, with heavy losses for the enemy.

For the moment, according to orders, one should dig in here well. Only the village along the highway to the left and a few hills beyond were to be taken to improve the front line.

The SS division had a small section of the large siege ring to hold. The fifth company, Arnold’s group among them, held their position with granite hardness, tough as steel. Even today, Wednesday evening, as they celebrated Fischer’s birthday in the mother’s little house, three men were on sentry duty. The rest sat in the room around the table with the company commander, who came with several of his messengers, as he had promised.

This German mother had lost everything. Before the Germans came, her situation seemed hopeless, with no way out, but still she had not given up home, but kept on bravely and courageously. Why? She had not known why. But now, everything had suddenly turned out so well.

Today she had the place of honor next to the birthday boy, and not everyone knew how to express his deepest feelings for her hospitality. She had baked a wonderful cranberry pastry, and there was coffee from the company stores. Finally, the woman brought out two bottles of vodka from the cellar, which she had probably been saving in the hopes of a reunion with her son.

The birthday party could not have been better back home. Everyone felt it was something remarkable. Back home in Germany, a mother was thinking about her distant son, alone on his birthday under who knew what conditions. If only she had known that he sat comfortably with his comrades, her worried heart would have rejoiced.

The company commander also thanked the woman for her gracious hospitality and the excellent refreshments. Then he turned to the birthday boy and expressed his hope that he would live at least four times as long as he already had. Two men from the group, squad leader Arnold and SS man Schmidt, then ordered him to stand. By order of the Führer and at the request of the battalion commander, he was awarded the Iron Cross for demonstrated bravery before the enemy. Everyone was happy, and the he was proud of the medal. The past days of hard battles flashed before their eyes. It had gone well so often before. The squad had often fought at the front of the company. Determination and endurance also would certainly be required of each man during this defensive period outside Leningrad.

But there was no time for daydreaming. As every evening as this time, the shells were beginning to fall.

Everyone stood up and put on their steel helmets. If things got to bad, one would have to return to the bunker. One looked through the open door into the night, springing back to take protection from flying shell fragments. German machine guns fired tracers at enemy positions. Their chattering was overshadowed by the shots of our own artillery, and by the howls and explosions of the enemy’s. The Soviets were firing light signals, narrow bright lines in the air that suddenly burst like fireworks and drifted down as many small stars.

“These light signals usually mean a strong Soviet attack,” said the company commander. “Is everything ready?”

Yes, one was ready. Let them come. They would get a worthy reception. The laws of war had to be obeyed.

Last edited 13 September 2025

Page copyright © 2010 by Randall L. Bytwerk. No unauthorized reproduction. My e-mail address is available on the FAQ page.

Go to the 1933-1945 Page.

Go to the German Propaganda Archive Home Page.