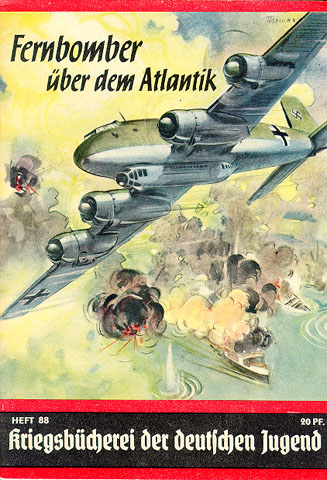

Background: The Nazi published a large number of 32-page booklets in a series titled “War Library of the German Youth.” They were intended to persuade the youth of the glories of war, and often included a pitch to enlist in the military. This one deals with the Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor, a long-range bomber based in France. They searched for convoys. I’ve not included the five drawings in this booklet.

The source: Carl G. B. Henze, Fernbomber über dem Atlantic. Erlebnisse einer ‘Condor’-Besatzung im Kampf gegen England (Berlin: Steiniger-Verlage, no date, but 1941). This is #88 in the series “Kriegsbücherei der deutschen Jugend.”

The thick milky fog hangs over the northwest coast of France, extending into the countryside beyond. One can scarcely see ten meters, and sounds disappear into the mist. Occasionally one hears voices. A truck honks over there, a dog barks in the distance, and a ship’s horn blows shrilly on the water. But there is nothing to see. The sounds are hollow and mysterious, coming from nothing and returning to it.

It is

January 1941. The fog has hidden the water and land for days, hindering

reconnaissance efforts by German aircraft and naval units. It hides the

enemy’s convoys that — loaded with war material and food for the

blockaded island — are coming from Canada or the U.S.A. The freighters

and tankers travel slowly, but securely, through the thick fog. The curtain

of fog stops the German long-range bombers that seek out enemy ships in

the Atlantic and send them to the bottom. The planes could take off easily

enough, since fog is no hindrance for planes today — but how could

the crews spot enemy ships? — — —

It is

January 1941. The fog has hidden the water and land for days, hindering

reconnaissance efforts by German aircraft and naval units. It hides the

enemy’s convoys that — loaded with war material and food for the

blockaded island — are coming from Canada or the U.S.A. The freighters

and tankers travel slowly, but securely, through the thick fog. The curtain

of fog stops the German long-range bombers that seek out enemy ships in

the Atlantic and send them to the bottom. The planes could take off easily

enough, since fog is no hindrance for planes today — but how could

the crews spot enemy ships? — — —

Several kilometers from the coast, the big birds of a long-range bomber squadron remain in their hangars. The airfield is somewhere in the north of France. The fog conceals the huge hangars and tents.

One hears hammering and pounding, and the occasional bit of a song that the men are whistling. Now and again one hears the call of the guards or the soft sound of a motorcycle carrying a messenger to headquarters. Only these sounds suggest that behind the fog, the life of the squadron continues.

In the ready room, squadron leader Captain Schindler walks back and forth, speaking at times to his aide sitting at the table reviewing the mail. The captain regularly looks out the window, taps with all ten fingers the pane, looking into the gray and hoping to see a shimmer of light announcing the end of this damned fog. He puffs on his cigar, the smoke of which follows him as he moves about the room, until it joins with the smoke from the aide’s short pipe.

Captain Schindler paces about. Then he stops by Lieutenant Behrenbrook’s desk.

“Behrenbrook, this is awful! All kinds of fat convoys are slipping through the soup out there and we sit here twiddling our thumbs or doing paperwork! This is the third day we’ve had this peasouper. I’ve never seen anything like it. Well, I do remember in Flanders back in 1917 we could not fly for five days. We had to sit in the junk and wait. I was 18 years old then — a newcomer — and could not either smoke or play cards. I learned how to do both perfectly in those five days.

The lieutenant shoves the stack of mail to the side and taps the smoldering tobacco with the bottom of his fountain pen.

“Captain, I think it will clear up today. I have a feeling that we will have lovely sunshine by afternoon.”

“And what do you base your feelings on, Mr. Behrenbrook? Have you looked at the barometer?”

“Yes, Captain, this morning at eight and now,” looking at his wristwatch, “at ten, it has risen four points.”

He smiles and points with his pipe to the instrument hanging on the wall.

The captain leans over the desk and raps the barometer with his knuckles. The dial moves up nearly two points.

“Right — Great! The meteorologists seem to have it right today when they predicted the fog’s end. But think of the fat convoy that reached the British Isles under its protection! — Well, if we can fly today and find some targets for our bombs, I’ll buy a few bottles after dinner this evening. Remind me!”

The lieutenant laughs.

“Will do, Captain. I think I can order the bottles already!”

Captain Schindler puts his cigar out in the ashtray and opens the window.

“Let’s at least get rid of the fog we’ve caused in here.”

He leans out the window, gazing into the gray fog that conceals the field and the hangars.

“The wind is blowing,” he says. “You may be right about those bottles.”

He turns around.

“Come on, Behrenbrook, let’s have breakfast. After that we’ll check things out.”

The two officers take their coats and caps. They walk through the fog, feeling an occasional bit of fresh air, to the dining hall.

Most of the pilots and observers have gathered there. Some write, others play cards or chat.

Captain Schindler and his aide sit down at a round table, joining Lieutenant Mayer, Lieutenant Seebohm, Lieutenant Wendler, pilot Lieutenant Herrmann, Corporal Jaksch and Corporal Springer, who are in the midst of a lively conversation. As the squadron leader and his aide eat breakfast, the “shop talk” continues.

Lieutenant Wendler, a young, boyish-looking blond officer who has already earned the Iron Cross, First Class, during a mission over England, is speaking. “Well, comrades, I’ve been there only three days and still do not know your large- four-engined planes very well. But I am looking forward to our first flight over the Atlantic.” Turning to Lieutenant Herrmann, he says: “ I hear that you were flying the ‘Condor’ even before the war?” Lieutenant Herrmann, a thin North German of about 28 years, takes a sip of coffee and lights a cigarette, since the Captain and his aide are done eating.

“You’re right, Wendler. I was an engineer back home, and was a test pilot for Focke-Wulf in Bremen for several years. I flew some of the first ‘Condors.’ When they were remodeled into long-range bombers during the war, I was transferred here from a reconnaissance group. I was delighted when the captain gave me command of his machine.”

“Well,” the captain said, “when I saw from your papers that you knew the big bird from back home, I wanted you for my pilot. My former pilot had to leave after a long illness. But tell us something about the “Condor.” The others will be interested, I’m sure.”

“Certainly, Captain. The growth of air traffic required long-range aircraft that could withstand hard use. Focke-Wulf, which had a long history as a good passenger aircraft, went to work on a four-engined plane. I think you know that our ‘Condor’ was designed by their Focke-Wulf’s lead engineer, Kurt Tank. He also designed other first-rate military aircraft.

The construction process was kept quiet until one fine day the big four-engined bird stood on the runway. We test pilots had our chance. Beginning with short flights that grew longer, we flew the ‘Condor’ over all of Germany. We saw how high it could go, and tested all the safety elements. After a while, we were ready for the first long flight. You may recall that Captain Henke and Captain v. Moreau, who later was successful in the Spanish Civil War, earned international attention by flying from Berlin to New York and back again.

That was on 10.8.1938. The 6371 kilometer flight took 20 hours from Berlin to New York, and 24 hours the other way. There were no problems in either direction. The ‘Condor’ had proved its ability as a long-distance aircraft.

Passenger traffic across the ocean was nearer than anyone had expected. Not long after that flight, the same crew — along with designer Tank — flew the same machine to Tokyo.

The results of these two long flights were evaluated as the series was constructed.

When the war began, nothing at first was heard of the ‘Condor.’ But when we had to show the English that the Luftwaffe could reach their convoys in the Atlantic, we needed planes that could operate hundreds of miles off the Irish coast. That’s where the new version of the ‘Condor’ came in. We’re lucky to be able to fly it far out into the ocean in search of victory!”

“Good. Now we know our long-range bomber’s history. As soon as the fog lifts, we will take off. I am sure we will find a few convoys and individual ships that we can go after. — Gentlemen, the barometer has been rising since this morning. The fog is lifting. Get ready, everyone. As soon as we can see anything, we will take off. We will meet in half an hour!”

Two hours later. The barometer was right, as were the weathermen. The fog has vanished. A fresh wind blows from the east. Scattered clouds at 400 to 500 meters are moving quickly west. A sunbeam shines through the gray clouds occasionally. A patch of blue sky is seen occasionally through the clouds.

Things are busy on the airfield. After meeting with the commander, the squadron leader has given orders in the operations room to the pilots and observers. Each crew has its operating area outlined on the large map of the Atlantic.

The aide is in his workroom. Like all other officers, he has tasks that have to be completed to ensure the squadron’s smooth operation.

Captain Schindler has organized his squadron such that they take off together, then separate after a time to head in groups for their respective areas. The groups will then split up too, but will remain in radio range to assist each other in attacking large groups of ships. The captain leads the first group.

While the mission is planned in detail in the operations room, the ground crews have received their orders. A successful mission depends on their conscientious efforts. They make the final preparations, loading heavy bombs and ammunition for the machine guns and other guns before rolling the planes to the runway. The motors are warming up. Their thousands of horsepower fill the field with a melodious noise. The mechanics in each plane check out their engines.

The crews arrive, six for each plane. Wearing their thick clothing, they find their places as the mechanics leave the machines and the pilots announce their readiness.

The engines roar as one huge bird after another rises into the air. They circle above the field, raising their landing gear as they wait to take their place in the formation.

Captain Schindler and his pilot Lieutenant Herrmann stand alongside his aide, who will fly on the left of the first group, and watch their comrades take off. Lieutenant Behrenbrook runs to his plane, which quickly takes off. The squadron captain’s plane takes off too, and takes its position at the head of the group. They head toward the enemy. The nine enormous planes, all identical, are a wonderful sight. The 36 engines rumble over the countryside. The ground crews watch “their” planes disappear into the distance. Their engines fade. Over the coast, the long-range bombers disappear into the grayish-white clouds. Now and again sun flashes off a wing, then there is nothing more to hear or see. A German long-range bombing squadron is looking for the enemy. —

The airfield is now quiet. Occasionally a messenger arrives on a motorcycle. The ground crews roll away the bomb carts and haul away the boxes. Then they head for the hangars to clean up the fuel and oil. The guards march between the entrance and the hangars. The gunners at the flak posts shift from one leg to the other in the cold, watching through binoculars as the sky clears. The clouds break up and disappear to the west. A cold pale winter sun shines over the field and through the windows of the quarters and hangars.

Hours will pass before the big planes return to their home field.

Far out in the Atlantic, hundreds of kilometers from the east coast, a British convoy is sailing. It has about fifty ships steaming behind each other. The convoy stretches over many kilometers. Several destroyers protect its flanks, like sheep dogs protecting a flock of sheep. They are there to protect against submarines and naval vessels. Many English convoys have already learned the value of this “protection” as they encountered German submarines.

Besides thousands of tons of merchant shipping, several destroyers usually hit the bottom ,too.

Huge masses of important war supplies are shipped from Canada and the U.S.A. There are about 35 freighters and 10 tankers carrying the supplies that will let the “island” keep fighting. They are carrying a total of 36,000 to 38,000 tons of valuable cargo.

The captain and first officer stand on the bridge of an 8,000-ton steamer. They scan the clearing skies.

“God damn,” the captain says, “I wish we were there. So far things have gone well. No submarines. The fog hid us for several days. The fog was no fun, and I’m surprised we had no collisions, but it did hide us from the enemy. But now, before reaching the Irish coast, we have to worry about German flyers. My colleague Br. in Boston told me that he barely escaped being sunk by a German plane 100 kilometers west of Ireland. They won’t miss our long convoy now that the fog has lifted.”

“You’re right, Captain,” replies the first officer. “They haven’t come this far yet, but I fear the Germans will cause us trouble. Who knows what surprises they may have. Back in 1938, they flew a four-engined machine nonstop from Berlin to New York and back. One of these days they will attack our convoys in the middle of the ocean.”

Similar conversations were taking place on the bridges of numerous ships in the convoy on this January afternoon. England could not forever conceal its rising losses at sea. Sailors at least talked about it constantly. Many had already experienced attacks by German submarines or planes.

The convoy steamed at full speech through the waves to reach the safety of the coast as soon as possible. But that was difficult, since the convoy was limited to the speed of its slowest vessel. The destroyer’s officers kept watch on the air and sea. They know well that they are of limited help in protecting their flock against air or submarine attacks. What can they do against a submarine that launches its torpedoes? And even though they are well armed, what can they do to hinder attacks by German flyers? They are more or less there for moral support. The English offices know that, as do the captains and sailors on the merchant ships.

But they have to try anyway. The naval yards, factories, war industries, and military leadership in England is waiting nervously for the ships that were loaded in Canada or the United States. Without them the war cannot be continued. Though thousands of tons are already at the bottom of the sea, the attempt has to be made.

As the convoy steams on, the captain of the previously mentioned 8000-ton steamer suddenly sees something in the sky. High on the eastern horizon he spotted some black spots and watched as they become three large airplanes heading for the convoy.

“German flyers!” he shouts. The destroyers and other steamers have also seen the rapidly nearing German planes. Sirens sound everywhere. The flak crews head for their stations. The convoy breaks up. Some captains lose their nerve and zigzag, a foolish action. The ships pass close to one another and more than once a collision is narrowly averted. The German planes have arrived and are dropping bombs before the destroyers can start firing their flak.

The Condor squadron leaves its airfield behind. The wintry landscape passes below. The big planes climb slowly, the BMW engines sing their song. The sunlight dances on the windows. The nine enormous planes are powerful testimony to German military might. They fly in formation over France. The soldiers beneath watch in admiration as the powerful bombers carry their loads of bombs against England’s shipping. The crews of the flak batteries below are delighted by the tight formation of splendid aircraft high overhead. They fly against England!

The commander and his squadron captain sit alongside the pilot. The engineer, radioman ,and both gunners are at their battle stations. The gunners keep careful watch, though no English fighters will show up in German airspace. In the rear, the heavy bombs are being carried by the four powerful engines.

Now they are over the coast. The white beach shimmers alongside the steel-blue ocean. Hours of flying are ahead of them. Their great range and high speed enable them to operate hundreds of kilometers from the coast.

The high quality of the engines ensures that these planes can operate safely far from land.

The squadron captain gives his orders. The squadron should separate into three groups and head for their assigned areas. One group is ordered to head for the Portuguese coast, the second should head right along Ireland’s coast to the Hebrides and Orkneys. Captain Schindler orders his own group straight out into the Atlantic, about the level of the southern tip of Ireland.

The three groups head off in their respective directions. Comrades disappear to the left and right into the light mist of an almost cloudless January sky, while the three planes of Squadron 1 fly onward. The sea is free of ships in every direction. The waves roll on endlessly. But the sea seems almost motionless from the planes. Only occasional white caps can be seen, a sign that the wind is increasing. Nothing of that is noticeable in the planes. A slight adjustment to the steering deals with any strong gust of wind.

Captain Schindler leans back in his seat in satisfaction. They have been flying for some time, and the land behind them has vanished into the mist. There is only water and sky around them. The captain says “Eat!” Each takes out his rations.

But they don’t stop watching. At any moment someone may spot smoke from an enemy steamer on the horizon. But the ocean is still clear.

As the captain takes a gulp of tea from his thermos, the radio announces:

“Smoke ahead!” The food is set aside. Right! There is a dark cloud of smoke to the left. The steamer is soon plainly visible. It zigs back and forth excitedly.

An English ship of about 4500 tons! It sits deep in the water, seemingly heavily loaded. Does it have “friends” in the vicinity? But there is nothing visible. It seems to be alone. What is its cargo? Well, that makes no difference. It has to be sunk!

Captain Schindler gives the plane to the left the order to sink it. While the other plans circle slowly, Lieutenant Behrenbrook, the plane’s commander, carries out the order.

He glides directly toward the Englishman and drops a light bomb before the bow. He circles around to give the crew time to launch their lifeboats. The ship’s two guns are clearly visible. The ship stops as the sailors hurriedly lower the boats. The Tommies row as fast as they can. Perhaps they will be rescued by a passing steamer, perhaps not. It is war!

When Lieutenant Behrenbrook is sure that the boats are far enough away from the steamer, he drops down.

A mid-sized bomb hits the ship. A thick cloud of smoke rises up, flames spring out. A hit.

The “Condor” circles the damaged steamer again. Its name is clear on the stern. The lieutenant takes a few pictures of the sinking ship. The last shows the bow in the air and foam as the ship sinks.

The lieutenant brings his plane back to join the other two airplanes. England has one ship less.

Captain Schindler looks at the map and determines the position. He orders over the radio: “Split up. If you see a convoy, let me know and we will resume formation!”

The other planes head off to the right and left, and Schindler’s plane heads straight. The sea seems dead in every direction. Albion’s command of the seas has already suffered major blows from German airplanes and submarines.

What is that? A submarine! Schindler turns his plane and heads for the submarine. The sub has no reason to dive. A comrade! The ‘Condor’s’ crew recognizes a German submarine keeping watch far out in the Atlantic. Several men on the tower wave to their comrades above while the large plane circles the sub.

Comrades, we just snatched a victim from you!

You’ll find others. There is no envy in the German armed forces. The Luftwaffe and navy are both fighting England and they attack whenever they meet it.

The “Condor” is again flying at the normal altitude.

The submarine has vanished, lost in the lonesome ocean.

Captain Schindler is back in his position. The “Condor” is far to the west of Ireland. The sun is gradually sinking — the short winter day will soon be over. That means a long night flight back home, but the moon is full and the crew of the “Condor” is just as familiar with night flying as their comrades flying fighters.

After a while the captain suddenly spots smoke on the horizon. The dark smoke is spread across the horizon. There must be a lot of steamers — a convoy! The captain radios the other two planes, and also the other two squadrons that should not be all that far away. The whole squadron is needed to attack the convoy on the horizon. The radio brings the answer of the others.

In half an hour they will all be there.

The two other planes have arrived meanwhile, and Captain Schindler decides to attack the convoy immediately. There will certainly be enough left for the other planes.

The smoke on the horizon grows clearer. The captain tries to count them. There must be at least 40 or 50 steamers in a long line.

And they are coming from the west. They must be heavily loaded.

Now several freighters and tankers are visible. Destroyers circle about. The three planes head for the convoy. The radio announces the remaining comrades are coming. Schindler decides he can attack with his three machines.

The comrades will arrive soon and join in. Let’s get going!

The other planes move into a favorable attack position. They can head directly toward the targets. By now they must have been spotted.

Several steamers are zigging, coming dangerously near each other. The convoy is falling apart. Captain Schindler sees that there are more than 40 vessels below, including some big ones. “Well, let’s go!”

The destroyers and some freighters are firing as the three planes fly over the line of steamers. Tracers from machine guns and light flak sizzle through the air, and the small guns of the freighters also send their greetings. That doesn’t hinder the attack. Well aimed dark gray clouds pop up to the left and right, but the planes are above the ships.

Ignoring the fragments hissing through the fuselage and wings, Captain Schindler’s plane is over a big freighter of around 5,000 tons. The comrades have also found their victims. A light push on the trigger and the “gifts” are on their way.

Captain Schindler hit the 5000-tonner amidships. Thick white smoke climbs up, showing a hit in the engine room. A 3000-ton tanker is spilling black smoke, hit by a bomb from Lieutenant Behrenbrook’s plane. The third plane has hit a remodeled passenger steamer of over 8000 tons. It is dead in the water and has been rammed by another freighter.

The destroyers and other ships are keeping up heavy flak and machine gun fire. Shells explode dangerously close to the large, but agile planes. Shell fragments whiz by, hitting the metal and tearing holes in the fuselage.

The pilots maneuver to avoid the enemy fire and circle above the convoy. Bombs keep falling! Several ships are dead in the water with holes in the deck or hulls.

The men fire the flak and machine guns frantically, hoping to bring down one of the “damned Germans.” But their efforts are in vain. The three long-range bombers fly low over several ships, their guns firing at the crews below and destroying their weapons.

The squadron captain breaks off the attack and the planes climb higher. The other two groups radio that they will arrive shortly. The first three planes quickly appear in the light of the sinking sun, then the other three. After brief radio conversations, they renew the attack on the enemy.

The convoy has completely fallen apart. The steamers are heading in every direction. The destroyers are firing every gun at the nine large planes. Each plane looks for a target, and bombs are falling everywhere from various heights. A few fall in the ocean, but most hit their targets. Gray, white and black clouds rise from the ships. Burning tankers glow red. Parts of ships fly through the air. Hell is breaking loose below. There are sinking, burning ships. Others are still in the water. The others are heading in every direction, not knowing how to escape the hail of bombs.

New bombs are exploding everywhere. A steamer blows up with a direct hit. In seconds, it vanishes. Lifeboats are cut in two by the bows of onrushing steamers.

England wanted war. He who sails for England sails into death!

The long-range bombers keep circling. Bomb after bomb falls on the confusion below. The ships’ guns continue firing. A destroyer has been hit. It disappears behind a white cloud. After a while there is a circle of foam, then nothing.

The air reeks of powder, smoke, and fire. Clouds of black, gray-white and greenish-yellow smoke hang over the damaged ships. Here and there foam indicates where a steamer has been sent “to the fish.” Here the bow of a ship is above the waves, there one has split in the middle.

Nine land-based aircraft are attacking an enemy armada, hundreds of kilometers from the coast. What are those down below thinking? The powerful modern German weapons over the Atlantic battlefield once again show the English which side has the stronger weapons.

Some of the steamers have made their escape. We’ve dropped all our bombs. They can form a new convoy over night. We or our comrades will be back tomorrow, or our submarines will find them. That will take care of the ones that got away today. Those that make it to England can report how “safe” British convoys are in the middle of the Atlantic.

This is the “break” in the war, according to English thinking. German flyers and German long-range bombers are not taking a break. They keep flying in winter and summer, regardless of the weather. They know how to find Churchill’s fleet—and hit it!

— — — While several ships keep firing flak impotently, the squadron captain gathers his flock together for the flight home. The sun has sunk in the west.

The sky and sea are gray and colorless. In several places, flames and red-gray smoke clouds are visible. The flashes of guns are also visible. They hope to shoot down a German plane as it flies into the night toward home. Hours of flying through the cold winter night are before them, but all is well. The fires of seriously damaged English ships light up the Atlantic darkness behind them,

The hours pass slowly, despite the great speed of the long-range bombers. The sky and sea are dark until light appears in the east — the moon. It rises slowly. Its silver light shines on the windows and metal of the planes. Occasional white clouds drift past the planes. The captain occasionally checks the condition of the wounded. The answers over the radio are reassuring. The one seriously wounded man is doing well after his thigh wound was treated.

Time passes. The clouds increase. The moon hides behind light gray high cloud cover. A light rain hits the windows, that gradually gather a layer of ice. The planes themselves ice up somewhat, but the de-icing equipment ensures that there is no danger.

Everything comes to an end, this mission included. In the dim light the coast appears below. No light shines from the villages and towns below. Now and again a searchlight stabs up. The German flak batteries are on the alert. They know that German planes are flying, but it is best to be safe.

The captain radios the landing field. They will be at X in 20 minutes. The answer comes quickly: everything is ready. Schindler gives the order to land. Fifteen minutes later the planes are in the hangars and are attended to by the ground crews. They will work all night, since the planes have to be ready for action again in the morning.

The crews freshen up, eat dinner, and go to bed. But work is not yet done for the squadron leader and his aide.

Reports on the successful mission to superiors must be made. While the captain is on the phone, the aide deals with the dispatches. The orders for the next day are discussed. Only then can both officers take their well-earned rest.

The next day the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht announces:

“German long-range bombers attacked a protected British convoy 500 kilometers west of Ireland. They sank a total of nine ships totaling 58,000 tons. Five ships were so severely damaged that they will probably sink. Four other ships were seriously damaged.”

It is several weeks later. The long-range bomber group has had steady successes against the British merchant fleet in the Atlantic. Thousands and thousands of tons of British shipping have been sunk or seriously damaged. From the Hebrides to Cadiz and off the Irish coast, the large “Condor” planes are flying, whatever the weather. In clear weather, fog or rain, or at night, they attack a convoy here or sink a tanker or transport there.

Captain Schindler and his second pilot Herrmann, who has since been promoted to lieutenant, have dropped their bombs over and over again. Both officers have alternatively flown the plane. With their squadron or alone, they have flown their reliable big bird with its four splendid engines, which have never failed them. The squadron captain has sent nearly 70,000 tons of enemy shipping to the bottom, giving the squadron particular pride.

The pilots and observers are sitting in the operations room on a rainy February evening. Their mission is to seek out individual tankers and freighters. They are large, fast ships that hope to escape German submarines and planes. They avoid the slower-moving convoys. Schindler’s squadron has been ordered to seek out these ships. The captain explains the situation and give the orders. They will take off between three and four in the morning and fly individually over the Atlantic.

The planes will be ready. The meteorologists predict the weather will not improve; in fact, it may worsen. Since there is no moon, they will fly in pitch darkness.

That is something different for the men of the long-range bomber squadron. Flying alone in such weather! That will show what the men and machines can do.

The captain stands. “Well, men, now you know. We have to sink at least one or two ships. We don’t have a real quota — but we sink what we see. I will come along. You know your positions. Be ready to take off at 3:30. Until then, good night!”

“Well,” Lieutenant Wendler says to Lieutenant Herrmann as they leave, “we will have to watch out that you and the captain don’t snatch the best targets from under our nose again. We’re pleased at your success, of course, but would like our share!”

Herrmann laughs and claps his comrade on the shoulder. “You have no need to complain that someone beats you to the prey. You’ve sunk 12,000 tons yourself in the short time you’ve been with the squadron. I won’t be surprised if you return tomorrow with some sinkings!”

“Hey, guys, stop fighting,” shouts the captain with a smile. Tommy still has a few ships for you. But get to bed. It will be tough flying in this weather. We need our sleep.”

By 9:00 p.m., the barracks are quiet. The mechanics are at work in the hangars. Soon the motors will be roaring again and the planes flying into the dark night. A strong west wind blows over the field. It howls through the trees behind the hangar, shakes the windows and doors, and whips the rain before it. — — —

3:30 a.m.! The planes are ready in the pouring rain. The crews are on board, and the signal to take off has been given. One after the other, the planes climb into the dark night and head for their destinations.

The wind blows strongly. It is nearly a storm. The captain’s plane, with him at the controls, takes off. The four engines roar, the propellers throwing the streaming rain against the windows and wings. The darkness is so thick that one can’t distinguish the sky from the ground. They fly blind. The instrument panel glows dimly, but the cabin otherwise is nearly black. The crew feels as if they are flying in a hermetically sealed room. The legendary darkness of Egypt cannot be any blacker.

The big plane fights against the rain. Schindler has to keep tight grip on the controls of the normally easy to fly “Condor,” which leaps through the air. No one is concerned; they know their captain and their plane.

Lieutenant Herrmann and his commander keep their eyes on the instruments. The lives of the crew depend on them. German workmanship proves itself again. The radioman, even more important than usual, keeps in touch with the base. Occasionally he hears from their comrades, gradually growing further away.

The sea is now visible below. The whitecaps make a remarkable sight in the dim light.

They fly for hours. Now and again the captain gives the controls to the lieutenant and looks over the map and reads the compass and the instruments.

Gradually it lightens up. The horizon is misty. Water and sky seem to merge. The plane is just under the clouds, and the rain is still pouring down. The altimeter reads 600 meters. Now the ocean is clearly visible. It’s quite a storm down there. The enemy ships will be having a rough time.

It won’t be easy to find those ships on the vast sea with such bad visibility.

The day is brighter now, at least as bright as it can get under such conditions. The sky above is gray, the water below endless. But no one is worried. The four reliable engines will keep them going.

“Ship to starboard,” shouts the lieutenant. The captain sees it too. A fat tanker is sailing near the gray horizon. The storm rips its smoke from the stack. Schindler looks more carefully: bright gray smoke, a short smokestack? It is a tanker, at least 10,000 tons. It is coming from the west — oil for England! Attack it!

The captain calmly gives his orders. Everyone is at his post as the plane plows through the storm toward the ship. One has to be careful in this damned weather that the bombs do not fall into the ocean. The aim has to be good.

The ship begins to zig. It looks like a new ship. But its maneuvering does little good. The captain knows how to get it.

They drop two bombs on the first attack. They bank as tightly as possible and watch! Did they hit? There, on the stern, and on the starboard side. Detonations. Two clouds of smoke and water rise up and are whipped away by the storm. There is a big hole in the side! But that is not enough. Another attack! Two more bombs fall and hit amidships. Gray-white steam rises everywhere. Oil leaks from the torn sides onto the wild sea around the ship.

It has had it. But Schindler is in the mood to attack. He turns and flies at the prey once more. All the guns are firing. He banks again and repeats the attack. The bridge and deck go flying under the fire. Then the captain stops. The tanker has had enough.

As they fly on they hear the tanker’s SOS. It is the 10,354 ton tanker “Taria,” first put in service by the Dutch in 1939. It is one of the largest and newest British tankers. It carried 15,000 tons of oil from the United States to England. But the 15,000 tons are now floating in the ocean.

The mission in the storm was worth it. The loss of the “Taria” and its valuable cargo will be a painful blow for Mr. Churchill. The ship is lost; it is too seriously damaged to reach port.

The captain holds the course for a time. The storm weakens, but the rain keeps falling. The clouds drop lower to about 300 meters. Visibility is bad. Maybe they will not find another steamer. There is not a ship or smoke cloud to be seen. Finally the captain, who has taken the controls again, spots smoke in the distance. The ship slowly draws nearer, and turns out to be a heavily loaded old 7,000 ton freighter. It sits deep in the water and is making headway with difficulty. It plows straight on. Either the captain has not seen the plane or thinks that it is English.

Whatever the reason, the ship keeps going, and lets the plane come nearer. The captain decides that the ship is English, and probably loaded with grain. The front guns fire a few shots to encourage the crew to abandon the vessel. Now Tommy seems to have recognized the seriousness of the situation. The crew hurriedly piles into the lifeboats as the plane circles overhead.

Schindler plants two bombs on the steamer’s deck. The old ship breaks in half. The bow and stern are visible for a time. Then there is only white foam and lifeboats.

Oil and grain — two important products for England! The captain is satisfied and gives orders to head home.

The home flight is uneventful at first. The enemy ships have vanished again. The captain makes notes for his report. The crew eats. Soon they are near England’s southwest tip.

The tip of land is under them. The tail gunner shouts into the radio: “English fighters!”

Instantly, everyone is ready for battle. The lieutenant holds the course, while all the guns prepare to welcome the Tommies.

“Three Spitfires,” the tail gunner shouts into the radio. The guns are already firing on the attackers.

Several bullets from enemy machine guns cut through the fuselage and fly out the other side, ripping big holes in the side of the airplane. But that is not dangerous, and does little harm to the loyal craft. The holes can be repaired easily.

The English aren’t bad shots and stay behind the big plane.

The commander gives the tail gunner a brief order, than banks sharply. He wants to see the enemy fighters himself. The battle lasts a while, but the Tommies seem to have great respect for the large craft. They keep a healthy distance.

The tail gunner succeeds in hitting one of the three broadside.

The Spitfire is quickly in flames and breaks up before the Tommy has time to bail out.

His two comrades circle around the “Condor” for a while before disappearing in the direction of England. One trails a white cloud of gasoline behind him. He took a hit.

“Well, we’re done with them,” the captain says, and sits up in his seat. “They certainly punched some holes in us, but thank God don’t seem to have hit anything serious.”

“The mission was worth it, captain,” replies the lieutenant. “We can chalk up two more ships on our tail and a considerable number of tons. And we can add another Tommy fighter to the four we already have.”

Soon they reach the northern coast of France. Schindler’s planes have returned, though one lost an engine to flak. The crew is safe and landed the plane. The comrades sunk another two ships. They can be satisfied with the night’s work.

The field is underneath. The captain shakes the wings three times, and the plane is greeted with cheers.

——— —- Soon they will be back in action. German long-range bombers are doing their part to bring England to its knees.

As the name suggests, long-range bombers are planes capable of flying long distances. The German Luftwaffe is using such aircraft for the first time in history to attack British merchant shipping far out in the Atlantic. Their range reaches far into the north, hundreds of miles off the Irish coast, and down to the African coast. German long-range bombers have proven to be very successful at destroying enemy commerce, making major contributions to the Battle of the Atlantic.

The four-engined Focke-Wulf “Condor,” developed from the passenger plane of the same name, is particularly well-known. Before the war, it set world records. Its high speed, bombing load, and wide range have made it a dangerous weapon. Many English convoys have been surprised by it, losing their biggest and most valuable ships to its bombs. Long-range bombers often disrupt convoys, making them easy prey for German submarines.

Great Britain quickly realized that the long-range bombers were a threat to its merchant fleet and to its supply lines. The British Admiralty has armed its merchant ships with flak guns of every variety, used barrage balloons. and increased the escort force. The increased defenses makes attacking ships in the Atlantic one of the most difficult missions. The long flights alone can exhaust the crews. Finding the convoys spotted by reconnaissance plants demands a high level of skill. Flying blind in bad weather and in icy conditions is a daily necessity. Often they fly distances that would have earned world records in peace time, when it was not necessary to fulfill military tasks as well.

Attacking armed merchant ships, particularly in convoys, requires courage and skill. They must fly low to hit the small targets, disregarding the heavy fire from the ships they are attacking. If the first bombs do not hit directly, they have to try a second and third time. Convoys are often accompanied by long-range planes. Along the coast, they even have to reckon with enemy fighters.

Long-range flyers know that attacking hundreds of kilometers out into the Atlantic, far from home, is dangerous. If they are brought down by enemy fire, they have to rely on themselves. In most cases, an emergency landing at sea means death. Still, the quality of the planes and their pilots’ abilities have brought some long-range aircraft back home, even with an engine destroyed. Each mission requires full readiness for action. Every ton of enemy shipping sunk or damaged testifies to that.

Last edited 3 Deccember 2025

Page copyright © 1999 by Randall L. Bytwerk. No unauthorized reproduction. My e-mail address is available on the FAQ page.

Go to the 1933-1945 Page.

Go to the German Propaganda Archive Home Page.