Background: This is a partial translation of a 128-page booklet about Japan first published in 1942 by the Nazi Party’s publishing house. New printings brought the press run to 700,000 by 1944. I include a full translation of the introduction and final chapter, with brief summaries of what is between. The last chapter is particularly interesting as a treatment of the Japanese army, an army vastly different from Germany’s. The book includes numerous photographs of Japanese life which are not reproduced here.

The author is a rather interesting person whose grandson provided me with further information about him.

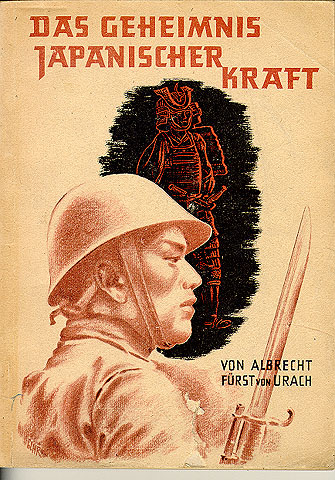

The source: Albrecht Fürst von Urach, Das Geheimnis japanischer Kraft (Berlin: Zentralverlag der NSDAP, 1943).

[Full Text]

The rise of Japan to a world power during the past 80 years is the greatest miracle in world history. The mighty empires of antiquity, the major political institutions of the Middle Ages and the early modern era, the Spanish Empire, the British Empire, all needed centuries to achieve their full strength. Japan’s rise has been meteoric. After only 80 years, it is one of the few great powers that determine the fate of the world.

What did the rest of the world, or we in Germany, know only

two generations ago about Japan? Let us be honest. Very little.

One had heard of an island nation in the Far East with peculiar customs,

of an island nation that produced fine silk and umbrellas from

oiled paper, that honored a snow-capped mountain as if it were

a god. They drank tea and had the curious custom of slitting

their bellies open. One had heard of smiling, powdered girls

with black hair and colorful silk clothing who strolled under

cherry trees and lived in houses of wood and paper. But one was

not sure if the small and sturdy men of this peculiar people,

some of whom came to Europe to learn eagerly, wore pigtails

and ate rotten eggs back at home, or whether one was confusing

them with the Chinese, since both peoples after all had slitted

eyes.

had heard of an island nation in the Far East with peculiar customs,

of an island nation that produced fine silk and umbrellas from

oiled paper, that honored a snow-capped mountain as if it were

a god. They drank tea and had the curious custom of slitting

their bellies open. One had heard of smiling, powdered girls

with black hair and colorful silk clothing who strolled under

cherry trees and lived in houses of wood and paper. But one was

not sure if the small and sturdy men of this peculiar people,

some of whom came to Europe to learn eagerly, wore pigtails

and ate rotten eggs back at home, or whether one was confusing

them with the Chinese, since both peoples after all had slitted

eyes.

Everything about Japan and the Japanese seemed attractive, a good place to visit on a world tour to enjoy the sights before European-American civilization put it all under protection to preserve it from decline, just as had happened to the Hawaiians, the Papuans, and the other small and dying peoples of the Pacific. One honestly regretted that so many interesting native customs were condemned to die out.

That was what our grandfathers knew about Japan. And today? Today Japan’s rising sun waves from the frozen northern sea to the coast of India. Today the once strongest powers tremble under the blows of Japan’s mighty power. Today the island nation of a hundred million Japanese leads with unbreakable will the millions of East Asia who make up a third of the world’s population. Today a huge kingdom has risen with a powerful heart where just 80 years ago an unknown people lived on their isolated island, satisfied with themselves and with no need or desire to leave the bounds of their islands. A powerful center of power has developed where only 80 years ago the conquerors and economic pioneers of Europe and America believed there was a colony that could easily be taken over.

That is the amazing and unique miracle of Japan’s meteoric rise. The world today looks in amazement. Amazed, astonished, and also terrified that they had not earlier recognized the mysterious causes, but also the compelling logic that led to this fabulous ascent.

We, the Axis powers, face the same enemies in our struggle in Europe as our Japanese allies. We understand what drives them to such accomplishments, for we too are today struggling for our existence and for our future. Still, the mysterious strength behind Japan’s unique accomplishments is a riddle for most of us.

Summary: The chapter provides a brief history of Japan. It suggests that Japan’s island status allowed it to develop free from foreign interference. On Japan’s racial background, the chapter says: “Scholars today do not agree on the racial origins of the Japanese people. It is important to know that the present racial composition of the Japanese people has been fixed since about the time of Christ.” The samurai are mentioned favorably.

Summary: The chapter brings Japanese history up to the 20th century.

Summary: The chapter concludes its discussion of Japanese industrialization with this paragraph:

Japan’s industrial structure is remarkable. Japanese experts followed the industrialization of Europe and America carefully. Japan succeeded in avoiding the atomizing tendencies of European industrialization and the growth of a rootless proletariat. Despite manifestations of capitalism, Japanese industrial capitalism never gave rise to class struggle. The common goal of both workers and owners — to build a strong Japanese fatherland — overcame all disputes about wages or other matters.

Summary: The Russo-Japanese War of 1905, World War I, the war with China.

Summary: The chapter covers many aspects of Japanese life, including a favorable treatment of the practice of harakiri.

The unique nature of centrally guided energy brought about the miracle of Japan’s rise. Japan’s soldiers, however, more than any other force built the nation.

Throughout Japan’s history, the warrior class embodied the best characteristics and highest virtues of the Japanese people. The leading military families that exercise political power nourished this spirit in the elite over the centuries. The active but also stoic Zen Buddhism perfected and refined the character of the Japanese warrior and gave it a clear ascetic tone that remains even today the essential characteristic of the Japanese soldier.

The warrior class was not only an armed instrument in the hands of the landed nobility or the major military rulers, but also an elite with its own class ethos. The samurai had to be able to do more than fight. He had to embody an elevated and noble form of everything Japanese in all he said and did. He had to stand out both militarily and in social life. The samurai class had great privileges, but also greater responsibilities. He owed absolute obedience to the landed nobility or the Shogun. But he also had deeper and broader obligations. He could not live a comfortable life on own his own land. His greatest honor was to bear the sword.

The Sword as Symbol

Since ancient times, the Japanese sword has been not only a means of power, but a symbol for everything that the samurai served. The sword is the symbol of justice which the samurai was obligated to defend under all circumstances. The Samurai class had the duty to promote social justice as well. There are countless legends of swords that recall our myths of swords in the Nibelungen tales. There are tales of swords that act on their own, without the necessity of their owners doing anything, of swords wielded as it were by a ghostly hand that struck down dozens of enemies. Other swords drew themselves from their sheaths and struck down unjust and evil foes. Even today swords are made by the same families that have forged them for centuries. Sword-making even today in Japan is more an act of worship than one of craftsmanship. The smith who passes on the secrets of his father to his sons fasts the day before he begins to forge a sword and undergoes purifying ceremonies, since the Shinto religion views physical cleanliness as a prerequisite to spiritual cleanliness. Clothed in ceremonial white priestly robes, the apprentices hammer the steel in unison. The master follows carefully the slow development of the blade, which at exactly the right moment he plunges into cold water. The holy process results not only in a strong blade; it also reflects the deep significance of what a Japanese sees in his sword.

One has to have seen the devotion and admiration Japan’s soldiers have before a centuries-old blade. They take a prescribed stance and hold their breath so as to avoid marring even with their breath the honored and shining blade that is perfect in every regard. Then one understands what significance the sword has for Japanese soldiers. It is not only a respected weapon, but also a symbol for everything that is the best produced by the Japanese race.

The samurai is pictured and described in every school book and picture book for small children. He is the model and noblest essence of being Japanese. The normally restrained Japanese, both men and women, weep in the theaters and movies when the heroic samurai dies in combat, all the while showing his passion and stoic attitude. Even in today’s modern and industrialized Japan, the heroic is esteemed as much as it was centuries ago.

As a result of modernization, the samurai class was scattered throughout the country and absorbed by the masses. Its members spread their formerly unique ethos throughout the population and had a profound educational impact on the whole nation. Japan’s new army was a people’s army with universal service. The idea that Japan’s officer corps today comes exclusively from the earlier samurai class is false. Japanese officers today come from the entire people. But it is true that the army has retained the purest form of the samurai spirit. It displays it clearly to the whole nation. The “three living bombs” displayed the samurai spirit in Shanghai in 1931. Three simple soldiers carried concealed bombs to open a passage for the soldiers who would follow them. The same spirit filled the tens of thousands who charged into the guns at Port Arthur in 1904/05 until the corpses filled the ditches and allowed their comrades to storm over them to capture the enemy fortress. It is the spirit of the samurai that allowed General Nogi to follow his emperor into death. It is the same spirit that filled the men in Japan’s tiny submarines who, assured of their own death, snuck into Pearl Harbor and delivered the decisive blow against the American fleet. It is the spirit that filled the stoops that stormed British fortress Singapore, that filled those who fell to prepare the way for Japan’s great military triumphs. They carried with them the ashes of their fallen comrades so that they too could participate in the triumph. The spirit of the samurai lives today with the same force that enabled Japan’s army, an army of the whole people, to fight its many recent battles.

The first requirement of the samurai is a readiness to give his life. Without this willingness even the best weapons are of no avail. First the spirit, then training wins victory. The spirit must from the beginning include the willingness to die. That does not mean that the Japanese soldier seeks death. Rather, in sacrificial death in battle he finds the most perfect fulfillment of his life. But he wants to achieve a goal through his death — the realization of justice, which is the highest manifestation of the divine will of the emperor. His first military goal is not his own death, but rather the realization of that for which he fights.

Death as such holds no terrors for the Japanese warrior. For the Japanese, death is not an end, but rather a stage in the eternal progression from ancestors to posterity. It is a door that is not the end, but the beginning. Death on the battlefield makes one a kind of god, a “Kami,” who does not dwell far from the living, but rather always and ever joins with millions of others to hold his protective hand over the Japanese nation and people. He defends their happiness and growth, and takes a living role in all the earthly affairs of the entire people. The fallen become divine, and remain close to the coming generations. They are honored by them daily and live on in the nation as models and defenders of coming generations.

The Army’s Training and Equipment

Training in the Japanese army puts the hardest demands on the soldiers. Training is conducted under the blazing sun and in bitter cold over the harshest terrain. Japan had two essential military tasks from the beginning of its modernization. It needed a strong navy to defend the island nation, and a strong army to defend the bridgeheads on the mainland that it established at the beginning of its modern history. Not only were two different types of military training necessary, but also two different foreign policy goals. The army secured the Japanese islands by expanding the bridgeheads on the mainland, while the fleet secured Japan from the south, where vital raw materials needed for Japan’s industry in the Southwest Pacific islands were under the control of foreign nations, but were near Japanese territory. Great deeds of heroism were done by Japan’s young army in its first battle against China in 1894/95. The numerically vastly inferior Japanese army defeated the Imperial Chinese army on every front. It proved advantageous that many Japanese officers, who before the German-French War of 1870 had held the French army in high esteem, had learned something from the best army in the world, the Prussian-German army. The Sino-Japanese War ended with Japan’s complete victory. But the world hardly noticed. The war was considered an internal affair of the East Asian nations.

During the years of peace that followed, Japan carefully and systematically built its military. The fleet was expanded, the army strengthened. Japan was able to risk the unexpected, and take on the strongest army that then existed, the Russian, in Manchuria. The world thought it a foregone conclusion. One laughed at the little Japanese soldiers and mocked their heroic efforts as suicidal, as the hare-kari of a nation gone crazy.

But Japan knew what it was doing. It knew that it was protecting its territory, that it had to defeat the growing Russian threat. The army and navy fought with identical grim determination. Admiral Togo had returned from England in 1875, where he had studied English naval tactics for many years. He won the battle at Tsuchima. It was a brilliant naval victory, the kind is rare in history. Togo’s naval victory led to a decisive turning point in the Russo-Japanese war, eliminating Russian sea power in the Pacific for decades. The historic message “Japan’s future depends on your actions today,” signaled from the mast of the flag ship “Mikasa”, was the spark that ignited a holy enthusiasm of the crews of the battleships, cruisers, and torpedo boats to win the battle.

Years of hard training paid off. The Japanese victory was complete. The tsar’s fleet sunk under the blows of the rising sun.

The Japanese naval academy in Etajima looks at first glance more like an ascetic leadership school than the training ground of Japan’s future naval officers, though every element of modern naval warfare is taught there. The training at this unique military school is ascetic, strict, and well-rounded. Only 200 of 8000 applications are accepted after the most rigorous examination not only of their technical and physical abilities, but above all of their moral character. 44 months of thorough training follow. A nine-month tour of duty abroad concludes the training. The English and Americans are known to smile in pity and shake their heads over the primitive accommodations of even the highest officers. But Japanese officers are trained to see that as natural. One accepts the most basic and cramped quarters as a way of increasing the defenses or the speed of the ship.

Japan’s raiders and pirates had roamed the entire Southwestern Pacific, but from the 17th to the 19th centuries the government prohibited all naval activity. But the naval spirit never died. It found a glorious resurrection three hundred years later in the men who built Japan’s navy and saw to it that the island nation was defended by a strong fleet.

The Japanese fleet has not lacked honor since its remarkable victory in the Russo-Japanese war. Only the best are chosen for the navy. The most modern technology of naval warfare is used. Japan’s island nature allows for a far more powerful concentration of naval power. Favorable harbors and proximity to the industrial strength of the home islands allow for a wide operating radius, while the English fleet depends on widely separated bases across the entire world, which results in a dilution of its striking power.

The Japanese naval leadership recognized these strategic advantages from the beginning, and built its fleet accordingly. Nonetheless, the Washington Naval Agreement of 1922 granted Japan a considerably smaller navy than England or America. As the terms of the agreement were announced, several Japanese naval officers committed hare-kari to show the public and the world that they saw the agreement as a humiliation of the whole Japanese fleet. England and America smiled at this “theatrical fanaticism” by Japanese officers. They smiled and felt secure in their numerically superior fleets, and in the quality of their naval officers, who came from the leading families of the plutocracy, and who did not want to give up their accustomed luxury when serving on warships.

What could America and England know of the sacrificial spirit of Japan’s heroes, who suicidally plunged down on enemy fleets at Pearl Harbor or the Malacca Peninsula? At best they could only defend themselves, but could do nothing against the released power of Japanese heroes, for whom life was nothing, the greatness of their Fatherland and their Emperor everything?

The Japanese army displayed the same heroic spirit. Since the beginning of Japan’s modern armed forces, it has gone from victory to victory. It never suffered a military defeat, rarely even a setback.

It is impressive to observe Japanese army cadets, whose training is as hard as the navy’s. Each morning before sunrise, they gather outside and bow respectfully in the direction of the Imperial Palace. Then each silently reads the famous declaration of the Emperor Meiji to his soldiers and sailors. I have seen Japanese officers on the battlefields of China who, after a bitter night battle, despite total exhaustion, before sunrise read the holiest possession of the Japanese soldier, the order of the Emperor Meiji, in a way that was a cultic expression of a commandment. Only then did they care for the wounded and the fallen. Only then did they place the ashes of fallen heroes in wooden caskets and arrange their shipment back to the distant homeland.

Honoring the Dead

There is no more moving remembrance of the dead than the annual commemoration in recent years at Tokyo’s Yasukuni Shrine for the heroes who fell for the fatherland. It is a nocturnal ceremony with no lights. Shinto priests call out the names of the fallen heroes so that they may join the pantheon of Japan’s heroes. It is as if the wings of those who died in the steppes of Mongolia, or the jungles of the Amur, or the plains of China and the tropic isles of the South Sea beat over the ranks of admirals and generals gathered to hear the priests of the national cult as they sing out their oaths in the spring night.

No one knows Japan who has not seen how the ashes of fallen heroes are received in harbor cities. Hundreds stand in rows in solemn silence, members of national associations, veterans, the national women’s league, and school children. They bow solemnly as soldiers, usually comrades of the fallen, carry the urns of ashes as if they were carrying something holy. The urns are delivered to the family members and brought to their distant villages. They sit in the trains in silence, holding the urns on their knees. Each who enters the train takes his hat off and bows deeply before the heroic spirit of the fallen and burns a small candle as a sacrifice. This is how the homeland honors its soldiers who have died on distant battlefields.

Japan’s army has been at war for ten years. Since the emperor’s soldiers marched into Manchuria, the flow of ashes of fallen heroes back to the Japanese islands has continued. For ten years the Emperor’s army has been practicing the hard lessons of its training, and proved its devotion with hundreds of thousands of sacrifices. The Japanese people know what these sacrifices mean, for their awareness of their common national fate and that of the national community has been clear since the earliest times.

The historic order of the Emperor Meiji lays out the moral conduct of Japan’s soldiers. It lays out not only their obligations to the fatherland, but also the relations between soldiers and officers, but also to the enemy. This order placed grave responsibilities on the army. The Japanese army is therefore filled with the will to sacrifice, but also demands as spiritual leader the same willingness to sacrifice of the entire nation.

The Emperor Cult

They demand this in the name of the emperor, since the Japanese army is directly subordinate to the emperor. In international relations that relate to the military security of the nation, the Japanese military insists on the deciding word. It took upon itself the responsibility for the Manchurian campaign without going through complicated diplomatic negotiations. The army, directly subordinate to the emperor, sees itself as the executor of the emperor’s sacred will. For the same reason, the army seeks its holiest task as educating the national spirit. As in no other land on earth, the army is the nation’s educator. The army tirelessly defends the national interest when weak politicians or industrialists with foreign connections saw humiliating compromise as the best policy. Many officers committed hare-kari when treaties or agreements were made that were inconsistent with the nation’s honor. Members of the army do not hesitate to remove statesmen and important personages who in their eyes stand in the way of the national interest. They feel themselves as holy executors of the godly order that encompasses the ancient strength of the Japanese people. Modern history is rich in such actions, which, however, happen only when in the eyes of nationalist circles Japan’s national honor is at stake. This fanaticism reached its high point in the rebellion of young officers in 1936, during which government leaders were killed and parts of the capital were occupied for days by fanatic Nipponese troops.

This may to our eyes appear to be mutiny, but it can only be explained by the spiritual condition of the Japanese, who saw that which was most holy to them, the greatness and dignity of their nation, at risk. As fighting samurai, they reached for their weapons to battle injustice.

The emperor cult’s strongest supporters are in the Japanese army. In honoring the emperor, they see the strongest expression of their national faith, for his ancestry reaches back unbroken to the sun god. The person of the emperor is the holiest thing not only on earth, but between heaven and earth. In the eyes of the Japanese, the emperor himself is a god.

These are ideas that are difficult to understand from our Western perspective, and hard to express in Western language. But the emperor cult, which one might call the ancestor worship of the entire nation, is not the private belief of individual Japanese. It is the core of the Japanese community. Without it, the Japanese would be only an interesting and unusually hard-working Asian people. The emperor cult not only raises the Japanese far above the other peoples, but also forms the most unique form of government, governmental consciousness and religious fanaticism in the entire world.

One can only understand the enormous power that the emperor cult gives the Japanese people which one has seen it in action in Japanese life. The materialistic peoples of America and England cannot understand this form of state religion. They do not comprehend it. They cannot understand the enormous strength the emperor cult gives the Japanese people. This strength is spiritual, and can outweigh superior fleets of battleships and armaments budgets. It cannot be measured in numbers, but it is there, wonderful and productive.

The relationship of the Japanese people to their emperor is that of the child to the father, the ancient family relationship of obligation and obedience. The emperor only rarely exercises actual power. The emperor incorporates less real power as the authority that stands far above temporary power. The Japanese owes obedience to his parents, who in turn care for their children. The family relationship does not end with a single generation, but continues eternally, just as the emperor’s family according to legend has continued since the beginning of the Japanese islands and will be as eternal as the Japanese people itself.

This faith finds its outward expression when the Japanese see the revered person of the emperor, or when the fanatically revered personification of Japan’s greatness and faith travels through the streets of the capital, or during a review of the most modern tank or air force units. The streets are scrubbed clean. Reverent silence falls over the capital. The masses stand respectfully in the side streets. When the emperor’s Mercedes drives past, the masses silently bow such that they cannot see him. It is not permitted to look upon the person of the emperor. Every Japanese, no matter how well educated, would see such a thing as an insult to a holy person and therefore to his own faith in the state.

The modern Japanese see no contradiction between the fact that the emperor today reviews the most modern weapons, and perhaps tomorrow within the holy precincts of the emperor’s Palace acts as the supreme mediator between heaven and earth. Following ancient customs, the emperor himself symbolically sows a rice field while his wife weaves traditional silk. The royal pair carries out both ancient Japanese practices. The Japanese people honor not only the royal house, but also the entire people.

The Army as the People’s Spiritual School

Just as the samurai saw his moral duty to defend justice against injustice, the Japanese army sees its task as the education of the people in social justice, according to the will of the emperor. They fight untiringly against everything they see as un-Japanese, against the harmful influences of individualism and capitalism. They fight for social reform and for the social betterment of the suffering masses. They do so not only because their own best elements come from the people, but because they see it as the fulfillment of their highest ethical duty. True to the samurai tradition, the army sacrifices its own good for that of the community. They demand that the Japanese people follow their model. The army is the strongest socializing force in Japan.

Japan’s army has always favored the strength of the spirit over the strength of the material. Only this has allowed Japan’s soldiers to win against overwhelming odds on battlefields everywhere. The willingness to be finished with life, to view death as not the end, does not mean that Japanese soldier seeks a hero’s death, though it is esteemed as the fulfillment of a soldier’s life. He keeps his military goal before his eyes when with stoic determination and fanatic will to victory he storms the enemy position. He has left everything, home and family, and does not expect to reaches its pinnacle during war, inspires Japan’s soldiers today. In warplanes, two-man submarines or in storming the bunkers at Singapore, it gives him the strength to overcome, the willingness to die, and an unshakable will to victory.

East Asia for the East Asians

The previous pages have summarized the unique miracle of Japan’s rise. Foreign policy, the world standing of its country, was always more important in Japan than momentary domestic issues. Still, the spread of Japan’s international power can be explained only by the internal political power of the Japanese people. The private and the economic has always been bound to the governmental whole. Japan’s miracle is the success of the first major planned economy, which stands in sharp contrast to the confusion and chaos of Europe and America. Japan has earned its present position by hard work.

The Emperor Meiji ruled in his time over 30 million Japanese. 74 years later, his grandchild rules over about 100 million. To them must be added the hundreds of millions of the Asian peoples who follow Japan’s leadership.

The ancient Japanese culture, once built of wood, bamboo, paper, straw, and silk, is today a civilization built of iron and steel, of factories and machines. Yet even today Japan’s strength rests more on its ancient culture than on the civilization of the 20th century.

Japan has always been a reservoir and defender of Asian culture. The old cultures of China, Korea and India no longer have their original strength, but they have not only been preserved in Japan, but have remained alive. That, too, is why Japan claims leadership of the peoples of Asia today, not only because of its technological superiority.

The Asiatic Monroe Doctrine was first formulated in 1934: “Asia for the Asians.” Today, less than a decade later, the greater part of this political demand has become reality. Ever more of Asia’s peoples live in areas ruled by Japan and are building a common prosperous East Asia. The peoples of East Asia know, esteem, admire and fear Japan more than the Anglo-Saxons. They have seen Japan’s explosive growth and the weak response of the Anglo-Saxons with their own eyes. They have seen what Japan can do. They have seen Manchuria change from a chaotic No Man’s Land to the center of a new Asian order under Japan’s strong hand. They know that Japan is the real power and center of East Asia and see in the Land of the Rising Sun not only the center of a spiritual rebirth of the ancient cultures of East Asia, but also the center of modern civilization. They increasingly send their students to Japan.

England and America closed their eyes to the phenomenon that had to lead to a Japanese explosion: the phenomenon of Japan’s steadily growing national strength. It is not surprising that these cold, calculating nations with their material outlook could not understand Japan’s spiritual values and strengths. It is incomprehensible that they ignored Japan’s growing population, with its necessary consequences. They even tried to hold back this irresistible natural process, using means that had to lead to the explosion we are seeing today.

The Strength of the Axis

National Socialist Germany is in the best position to understand Japan. We and the other nations of the Axis are fighting for the same goals that Japan is fighting for in East Asia, and understand the reasons that forced it to take action. We can also understand the driving force behind Japan’s miraculous rise, for we National Socialists also put the spirit over the material. The Axis Pact that ties us to Japan is not a treaty of political convenience like so many in the past, made only to reach a political goal. The Berlin-Rome-Tokyo alliance is a world-wide spiritual program of the young peoples of the world. It is defeating the international alliance of convenience of Anglo-Saxon imperialist monopolists and unlimited Bolshevist internationalism. It is showing the world the way to a better future. In joining the Axis alliance of the young peoples of the world, Japan is using its power not only to establish a common sphere of economic prosperity in East Asia. It is also fighting for a new world order. New and powerful ideas rooted in the knowledge of the present and the historical necessities of the future that are fought for with fanatical devotion have always defeated systems that have outlived their time and lost their meaning.

Page copyright © 1998 by Randall L. Bytwerk. No unauthorized reproduction. My e-mail address is available on the FAQ page.

Go to the German Propaganda Archive Home Page.