Background: This is one of a number of “party histories” published after the Nazi takeover of power in 1933. The book covers the Nazi Gau Hessen-Nassau, which included Frankfurt. The author was born in 1898. A baker by profession, he joined the Nazi party in September 1923, just before Hitler’s Beer Hall Putsch. He had a variety of party positions, and was also a member of the Reichstag. In the introduction, he claims: “In the following work, I attempt to follow the course of the NSDAP’s struggle and victory in Gau Hessen-Nassau in general, and in Frankfurt am Main in particular, sticking as close to what really happened as possible.” I here translate excerpts from the book, which gives an interesting Nazi perspective on the period before 1933.

The source: Adalbert Gimbel, So kämpften wir! Schilderungen aus der Kampfzeit der NSDAP. im Gau Hessen-Nassau (Frankfurt: NS-Verlagsgesellschaft, 1941).

I remember two meetings from the early days of the movement at which

party comrade Sprenger spoke, since they plainly  reveal

the spiritual weapons of our opponents of that day. Two fervent men, party

comrades Kuntsche and Heinrich Müller (bearers of the NSDAP’s Golden

Badge of Honor), accompanied party comrade Sprenger to a December 1924

meeting of völkisch reflection and thinking in the Frankfurt

suburb of Ginnheim. It must have seemed hopeless, absolutely hopeless,

for the brave speaker and his two men sat in a hall surrounded by 500

people who were worked up into a hate-filled mob by planned and evil agitation

before the speaker even began. The culprit was the all-too-well-known

and ever present Herr Broßwitz, a Social Democratic Reichstag representative

and editor of the Frankfurter Volksstimme. At the moment party

comrade Springer began to speak, he cried out “Kill him! Kill him!”

Others took up the cry. It was almost a miracle that party comrade Sprenger

managed to say anything at all! He found a brilliant way to reach those

seated before him. He did not reply in the same manner, with shouts and

insults, but rather appealed to the soldierly honor of those men with

clenched fists. “Just about everyone here,” he said, “a

few years ago wore the field-gray uniform of a soldier. If we had captured

a single enemy soldier, and dozens of our men stood around him, would

anyone have thought about killing him? Any one of you would have been

ashamed to hurt him, even though he was an enemy. But I stand before you

alone, not as an enemy, but as your friend, someone who wore the uniform

of a German soldier for four years. I only want to speak as a soldier

to soldiers about why our heroic struggle was in vain, about why Germany

is in such a miserable state today, and what we can do about it.”

Broßwitz had not planned on that. These were soldiers who once again

understood each other as they had before, and for two hours they listened

to the man whom they had greeted with wild threats. The results of Sprenger’s

speaking in December 1924 were clear in the next election. In a notorious

communist neighborhood in Ginnheim, we received twenty-seven votes.

reveal

the spiritual weapons of our opponents of that day. Two fervent men, party

comrades Kuntsche and Heinrich Müller (bearers of the NSDAP’s Golden

Badge of Honor), accompanied party comrade Sprenger to a December 1924

meeting of völkisch reflection and thinking in the Frankfurt

suburb of Ginnheim. It must have seemed hopeless, absolutely hopeless,

for the brave speaker and his two men sat in a hall surrounded by 500

people who were worked up into a hate-filled mob by planned and evil agitation

before the speaker even began. The culprit was the all-too-well-known

and ever present Herr Broßwitz, a Social Democratic Reichstag representative

and editor of the Frankfurter Volksstimme. At the moment party

comrade Springer began to speak, he cried out “Kill him! Kill him!”

Others took up the cry. It was almost a miracle that party comrade Sprenger

managed to say anything at all! He found a brilliant way to reach those

seated before him. He did not reply in the same manner, with shouts and

insults, but rather appealed to the soldierly honor of those men with

clenched fists. “Just about everyone here,” he said, “a

few years ago wore the field-gray uniform of a soldier. If we had captured

a single enemy soldier, and dozens of our men stood around him, would

anyone have thought about killing him? Any one of you would have been

ashamed to hurt him, even though he was an enemy. But I stand before you

alone, not as an enemy, but as your friend, someone who wore the uniform

of a German soldier for four years. I only want to speak as a soldier

to soldiers about why our heroic struggle was in vain, about why Germany

is in such a miserable state today, and what we can do about it.”

Broßwitz had not planned on that. These were soldiers who once again

understood each other as they had before, and for two hours they listened

to the man whom they had greeted with wild threats. The results of Sprenger’s

speaking in December 1924 were clear in the next election. In a notorious

communist neighborhood in Ginnheim, we received twenty-seven votes.

In 1925, we held a meeting in the Frankfurter Hof, a restaurant in the peaceful Frankfurt suburb of Hausen. When I say peaceful, I mean only that the larger part of the dear population of the area would have gladly eaten us “handful of damned Nazis” raw or baked at any time. There of all places the “Nazi bandits” chose to set foot, and present the chief of their “Society of Three” as speaker! Three of us accompanied party comrade Sprenger. One could not speak of a protective brigade. The opponent, of course, saw that, and constantly interrupted the meeting, trying to bring it to a violent end. Scarcely had party comrade Sprenger begun to speak when a water bottle was thrown at him. Only Sprenger’s quick reaction kept it from hitting him in the face. We kept that unusual trophy in the party office for a long time. Sprenger continued in a calm and steady manner, as if nothing had happened.

For some reason, nothing happened after that. Sprenger got into things and sharply attacked the “leading men” of the day. The meeting finished without disturbance. I believe to this day that the wild characters respected such courage and cold-bloodedness, and tried to imitate it by being decent themselves.

In 1926, party comrade Sprenger spoke to countless meetings in the countryside, most of which ended with the founding of a cell, a strong point, or a local group. One of these meetings was in the Marxist fortress of Nieder-Selters. The meeting was held outdoors. That was probably why it was not banned, since they thought their sheep were safe. But some workers were amazed at the firm, disciplined men in brown shirts.

They were supposed to be Nazi bandits, slaves of capital, murderers of workers! One really had to see them close up, to learn what they wanted! Getting them there was already a success, and party comrade Sprenger did not let up. The second time we came, there was even an restaurant owner who, despite all the threats, was willing to rent us a room. People predicted that this would be our last meeting. The opponent would mobilize all his forces. Party comrade Sprenger’s topic was provocative: “The SPD as the protector of capitalism.” As soon as the speaker had spoken his first sentence, the rage and hate of the whipped-up crowd spilled out. Party comrade Sprenger’s voice thundered out: “We are in charge here. If you don’t want to follow our rules, there’s a door you can use!” Silence for a few seconds: “Let’s have at it” was probably in the mind of each attendee. “S.A.! Tighten your chin straps!” The order cut through the thick silence — and that was the end of Marxist-pacifist courage. The Reds saw retreat as the better part of valor. And that happened in a Marxist fortress in our Gau! A few hours later, one of the crazy Red heroes fired some revolver shots at the house of the meeting’s chairman.

The cannonade did no damage to our side. I do not know if it had any impact on the shooter.

I could fill a whole book with stories of the Gauleiter’s activities and battles, but for the time being I will let these experiences of party comrade Sprenger in the early years of the movement suffice.”[pp. 19 - 22]

At the beginning of this year [1926] there was an important restructuring of the fighting organization. Under the leadership of party comrade Josef Geiger, a group of particularly loyal SA men formed the Frankfurt a. M. unit of the S.S. This was only second S.S. unit in the whole country. The S.A., too, was built up through untiring effort. A sixteen-member band was established, and since the sixteenth man was lacking, I had to join in whether I wanted to or not. That is how things were then. A party member was put to work where he was needed.

In the tough struggle for the countryside, every inch was a struggle. The biggest problem in rural villages was securing a meeting room. In one place, a minister misused his power and pressured the restaurant owner. In another place, it was the all-powerful Red mayor who threw whatever roadblocks he could in our way. Still elsewhere, our efforts failed due to the thick skull of the leader of the Farming Federation.

If after all the effort and our best persuasive efforts we succeeded in finding a small room, we could be sure that some local bigwig, notebook in hand, would be standing outside taking down the name of anyone who dared to attend a meeting held by those damned Nazis. Another method used to keep people from attending our meetings was for the united opposition to stand in ranks outside the doors, forming a living wall that kept people from entering. Those were all ineffective methods. We did not let ourselves be stopped by them. It made no difference to us, and we did not give up, even if someone attempted to block us by noise or terror, or through a silent boycott. In the latter case, sometimes the only person present was a policeman. Over time, we learned when we had to respond with force to get started, or if it needed quiet and determined effort. We had some failures, of course, but those failures, which we owed to the united efforts of our opponents, hardened us. We never lost our sense of humor, and already back then we laughed about this story:

A meeting was planned for a small town in the Kinzig Valley. The spacious hall was empty. No one had come. A student who chaired the meeting, and our speaker, sat alone for fifteen minutes, half an hour. The door suddenly opened. Three people came in, gave a friendly smile, and sat down at a table. Grinning, they waited for the speaker to begin speaking about his topic: “The Jews are our misfortune.” But what? The speaker stared at them, chuckled, packed up his belongings, and vanished. The three people were local Jews who had organized the boycott against us.

In late summer of 1926, we organized a large meeting in the world-famous spa city of Wiesbaden for the first time. The course of the meeting proved how wise it had been to bring the Frankfurt S.A. along to guard the meeting. The Wiesbaden S.A. at that time had only ten or twelve members. Since the spa city was in occupied territory and since the English banned uniforms, the Frankfurt S.A. came in civilian clothing. The small National Socialist group in Wiesbaden, under the leadership of party comrade W. G. Schmidt, had worked hard to find a small meeting room. In genuine Jewish fashion, the Children of Israel attempted to pay the restaurant owner 3,000 marks if he would cancel the agreement. For a few seconds, the Wiesbaden party comrades considered the restaurant owner’s proposal to split the 3,000 marks. The small National Socialist group in Wiesbaden, which suffered from a chronic cash shortage, could certainly have put the money to good use, but their desire to hold a large public meeting made it easy to say no. The hall was packed that evening. The Reichsbanner, lead by the so-called Reich Federation of Jewish Front Soldiers, showed up in force, and the communists joined in. The Red Brothers gathered their main force outside the hall, led by the Jew Wolf. About forty or fifty members of the Jewish guard took up a position in a corner near the entrance. That was admirable, as it made throwing them out easier. Their plan was to break up the meeting, thereby driving the attendees into the arms of their main force waiting outside. Our speaker had scarcely begun when tumult began in the kosher corner. At the same time. Chief Jew Wolf attempted to cause an uproar by entering the hall without paying the admission charge. Instantly, party comrade Weitzel and ten sturdy Frankfurt S.A. men dashed to the entrance, where the enemy forces were attacking. Only the Jew Wolf succeeded in squeezing through, while the other attackers were shoved back. He got a beating. Party comrade Weitzel ran to a table and threw an even dozen beer glasses at the corner held by the Jewish front fighters. The battle now reached its high point. Glasses and ash trays crashed, chairs shattered, and the shouts of the fighters all joined to make the characteristic sounds of a meeting hall battle. After five minutes, the Jewish front soldiers and their banana friends [The SPD paramilitary group was the Reichsbanner, which the Nazis mockingly called the Reich Bananas] had been tossed out of the hall. Our brave S.A. held the battlefield. The police, who showed up only after the fight was over, wanted to close the meeting. They were frustrated by a party member who jumped up on a table and shouted: “I am a Reichstag representative. The meeting will not be closed!” As a result, the meeting in fact did continue.

Just two days later, there was a second National Socialist meeting in Wiesbaden. Once again, the Frankfurt S.A. and S.S. came to provide a guard, but our departure was delayed because the System-loyal police, displaying a diligence that would have been admirable in a better cause, searched everyone and confiscated anything that could in any way be used as a weapon. Safe is sure, the police thought, and searched us again in Rebstock, which was the border between the occupied and unoccupied territories. This delayed us for two hours, but could not stop our trip to Wiesbaden. But we had an unpleasant surprise when we arrived. The meeting hall was the Paulinenschlößchen, famous in Wiesbaden and the surrounding area. It was packed, and the police refused to allow us in. We could not stand outside the place, and splitting up our group would have been suicidal. There was nothing left to do but march back. We had scarcely left the police behind and marched into the darkness of the spa grounds when about 500 men, armed with thick clubs and brass knuckles, attacked us. There were about 60 of us, and we found ourselves instantly surrounded by overwhelmingly superior forces. A group of about 25 with the leader at the front forced its way through, but had to instantly undertake a counterattack to rescue a beaten comrade lying on the ground. Only a retreat to a fancy hotel saved us from the Red forces. The police then took us in their cars to the city limits. But we could not think about heading home as long as a single comrade was still missing. A commando group was sufficient. The S.A. and S.S. men tore down a picket fence, and made themselves clubs. Now they were armed. Anyone who even gave us a dirty look got his reward. Except for a few who later came home on the train, we found the comrades again. Some of them were badly hurt. Our anger over the blow was partially alleviated by this successful second action.

Many know Frankfurt (M)-Griesheim as the site of a major plant of the world-famous I. G. Farben Company. For us Frankfurt Nazis, the name reminds us of one of the hottest battles in our political fight for power. I do not exaggerate when I say that the suburb of Griesheim was one of the strongest Marxist bulwarks in our area before our takeover of power. That is exactly why we had to do something. We were clear from the beginning of the dangers. Local group Griesheim was then Section VII of local group Greater Frankfurt. In 1926, it was led by party comrade Alfred Hättasch.

After thorough consideration of the situation by party comrades Sprenger, Hättasch, Hirt, and myself, we decided to hold a meeting in Griesheim, and, indeed, to go into the lion’s den itself, the Mainzer Rad, the Marxists’ favorite pub. We needed permission to hang posters on the poster pillars, but the Griesheim advertising office was headed by a well-known SPD man. No one would argue that our attempt to break into Red Griesheim stood under favorable auspices. Our “friends” openly promised a violent reckoning with us days before the meeting. The tested Frankfurt S.A., about 40 men under the leadership of party comrade Hirt, was ordered to Griesheim. Since Griesheim was in occupied territory, the S.A. and S.S. men could not travel in uniform. They were also explicitly warned not bring any weapons along. Later, it turned out that three S.A. and S.S. men nonetheless took along several small items.

On the afternoon of the meeting, the local leaders of the KPD and SPD met in the Mainzer Rad, and agreed that the NSDAP meeting had to be broken up at all costs. The exact details of how they planned to break up the meeting are known. The owner of the Mainzer Rad passed the information on to our party comrade Hättasch and asked him if, under these circumstances, he intended hold the meeting, which he, of course, affirmed. The planned speaker was party comrade Gemeinder. An hour before the meeting, party comrade Hättasch and I went to the room and set up a table to collect the admission charge. After 15 or 20 people had peacefully paid the admission, the Frankfurt S.A. and S.S. arrived with the news that party comrade Gemeinder could not come, and that he was being replaced by party comrade Simon, the leader of the National Socialist students in Frankfurt. Next, a well-known communist appeared at the table, drunk, and, in a provocative way tried to get in without paying. That was naturally a guise to conceal the true intentions, since behind the drunken provocateur a dozen of his comrades suddenly appeared. They punched me, charged past the table, and into the hall. Their leader sprang up on the stage and shouted: “Come on in, comrades!” Simultaneously, windows broke, revolver shots rang out, and the opponents jumped into the room through the broken window. Some of our S.A. men barricaded themselves in a corner. To confuse our opponents, party comrade Weitzel tuned off all the lights. In the confusion and darkness, party comrade Franz Krug of the Frankfurt S.A. dove into the thickest pile of the opponents and, after a brave defense, was beaten down. I finally got to party comrade Hättasch and told him to call the police as fast as possible, for our situation was hopeless. On the way to get the police, party comrade Hättasch met a doctor, and asked him to provide help to the wounded who were following him. With the excuse that he did not want to have anything to do with political matters, this peculiar doctor refused to help, despite the fact that one of the wounded had a serious head injury and a stab in a lung (party comrade Ludwig). The doctor even refused to use his telephone to call an ambulance. Later, the first aid section at I. G. Farben was notified, and they immediately sent their ambulance. However, the Marxists stopped it from helping the injured S.A. and S.S. men. The ambulance driver was forced to head back home. Meanwhile, the police showed up at the Mainzer Rad, but only to arrest those National Socialists who were present. Only one party comrade managed to escape in time, party comrade Hättasch. But as he returned to the meeting place and learned what had happened, he asked for the quickest way to the police station to stand by his comrades. The opponents only mocked him. He was thrown to the ground and kicked and beaten with brass knuckles and other such items, until he lost consciousness. A Stahlhelm man prevented these pacifist apostles from their last act of kindness, throwing him into the Main River. He called the police, who hauled party comrade Hättasch off to jail in the truest sense of the word, since he could not go on his own strength. I was also arrested, on orders of a French criminal policeman, a member of the occupying force. The Reds had not forgotten to set them on us either. Despite the fact that I had an escort of policemen to my right and left, the path through the raging mob was a challenge. Blows came at me from every side. A desperate character danced a wild war dance around me, waving a knife in the air. My eyes did not leave his hand, and one can imagine that I walked rather awkwardly to the police station. Not only did I have to dodge the blows, but also had to assume that at any moment a knife might plunge into my body. After identifying myself, I was released once the street was halfway calm again. Party comrades Franz Krug, Gutjahr, Fink, and Hättasch were taken to court in Höchst the next day. With the assistance of a French officer, they were released after a few days after posting a bond of 150 marks, which took a telephone call to Frankfurt. Later, the “criminals” were convicted in absentia by a French military court in Mainz and sentenced to three months in prison and a 250 mark fine. [pp. 34 - 41]

1927 was of particular importance to Gau Hessen-Nassau, both from the organizational and battle standpoints. From the standpoint of our opponents, 1927 was not at all bad. For the first months of the year, the public hardly knew we existed. The Jewish newspapers chattered triumphantly that: “National Socialism in Frankfurt (M) and Hesse is dead!” Those rotten big mouths soon learned how much life force the young movement had. The pause in our activities was not the result of our will or a sudden lack of courage. Rather, financially we were in an almost hopeless state. Organizationally, we were in the middle of a difficult crisis. The problem was solved when the Führer gave the leadership to the best man in Gau Hessen-Nassau, party comrade Sprenger. Party comrade Sprenger took over his new office under an impossible financial burden. Sprenger’s actions demonstrated the abilities of a careful and conscientious German official. “When we have spent our last penny, we will work so that the others do not realize it.” The Gauleiter realized that making war demanded a war treasury, that one cannot fight for order and cleanliness when one has debts and is oneself in disarray. The young hotheads in the Frankfurt movement did not understand their Gauleiter. They dreamed about and talked about great deeds, and held party comrade Sprenger for a weakling. There were splendid hotheads in this young generation, but with the characteristics of youth, they lived in the clouds and did not notice that their feet were no longer on the ground. Their Gauleiter, to the contrary, had both feet on the ground and worked untiringly to build up the organization of Gau Hessen-Nassau-Süd, which later become a model for other Gaue.

Part comrade Gemeinder took up the leadership of the Frankfurt local group. Since working conditions in the former party office, the 5th floor of the building at Domstraße 12, had become increasingly unacceptable, party comrade Gemeinder decided to rent a new office.

But desire was not enough. We lacked money! Finally, we were forced out of our airy loft. The landlord threw us out, under pressure from our opponents. We moved to the third floor of the building at Trierische Gasse 7, and there only after several landlords had given us the cold shoulder.

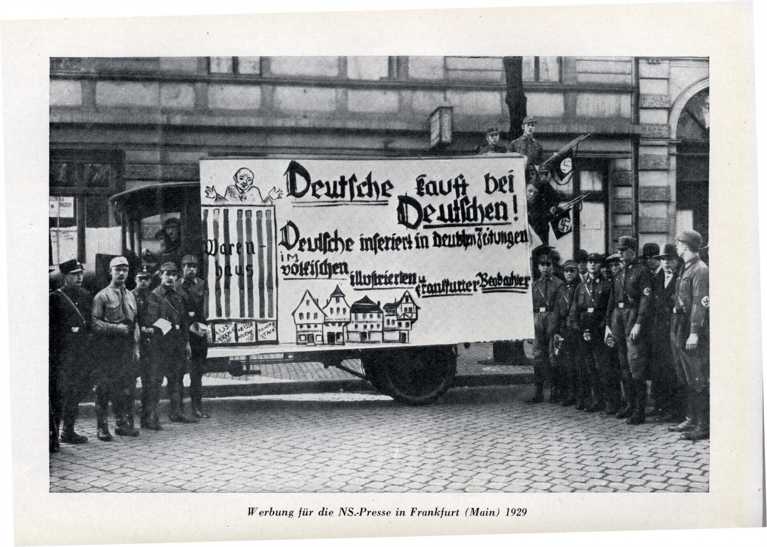

At Trierische Gasse 7, we could for the first time post our honest name, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party,” on the building directory. The window carried the proud inscription: “Frankfurter Beobachter Publishing House.” Now the Frankfurter Volksblatt, back them it was not a daily newspaper, but rather appeared just once a week. However, we had our own public newspaper, and that was of great value. Formerly, we had no opportunity to correct the lies of the press, since no Frankfurt newspaper would open its columns to us. We had no defense against the poisoning of public opinion against us. An event to which I will return later gave us a frightening look at the contemptible methods of poisoning the people through the press, showing at the same time the absolute necessity of establishing our own newspaper so that we could speak to the public. Party comrade Gutterer received the assignment of looking into the founding of a newspaper. Our party comrade Gutterer already had the plan firmly in his active mind, but he could not print the money necessary to begin a party newspaper. But the risk had to be taken. During a discussion evening on the theme “Criminals, Crooks, and Jewry,” party comrade Gutterer developed the plan to establish our own newspaper. It was met with great enthusiasm, and Gutterer used the enthusiasm of those present to pass the hat and collect about 48 marks.

That was our party newspaper’s founding capital! The editorial office was set up in a small room of party comrade Moßbrugger’s on Adalbertstraße in Bockenheim. The room housed the publishing house, the shipping office, and everything else that had to do with a newspaper. Party comrade Habicht from Wiesbaden was the editor. The paper was printed by party comrade Edel in Lambrecht (Rheinland-Pfalz), since no printing firm in Frankfurt was willing to take on the job. Party comrade Gutterer was responsible for the Frankfurt side of things, and also for the financial aspects. Anyone who knows anything at all about newspaper publishing will have to grant that it took enormous energy and unlimited devotion to the task, to the idea, if one were to have the courage to found a newspaper with such primitive resources.

For a very long time, the Frankfurter Beobachter was our problem child, and I believe it cost our Gauleiter more sleep than anything else back then.

Later, the publishing house moved to the party offices on Trierische Gasse, which now housed everything: Gauleitung, the leadership of the local group Greater Frankfurt, and the editorial offices of the Frankfurter Beobachter, while also serving as the meeting room and office for our city council representatives. This made the rental costs for the individual offices much more bearable! Outwardly, it was a thin, insignificant looking little paper, this new newspaper, but its language was clear and direct. It went after our opponents both to the right and left with cleverness and force. Reading it was a pleasure. Obviously, the Frankfurter Beobachter’s forceful attacking spirit won us many friends. And naturally, the sharp, fearless language of our newspaper led to legal difficulties. Our opponents undertook a major campaign against the editor, party comrade Gutterer, hoping through constant court cases and fines to silence this unpleasant and stubborn man. One day, Gutterer stood once more before the court because the Frankfurter Beobachter had carried two articles about the dishonest sales practices of the Jewish Wronker Department Store. It was conclusively proved that the half pound packages of butter Wronker sold were always ten grams short. One can imagine how much Rebbach Wronkerleben made through his dishonesty when one remembers the huge business that the department store did in food. General Director Wronker, who sued party comrade Gutterer, was not at all bothered by the facts demonstrated before the court, but rather by the accompanying remarks about “Jewish dishonesty.” The court clearly established the fact that butter was sold that did not have the advertised weight, but nonetheless sentenced party comrade to a 100 mark fine for libel. In another case, the result was even worse for our party comrades. The lack of good sense of the day was made clear when the Chief Rabbi of Frankfurt (M) — if I remember rightly, the caftan wearer was named Salzberger — was asked to dedicate the war memorial. Gutterer addressed this scandal energetically in the Frankfurter Beobachter. It is true that he wrote of “Jewish insolence.” After a five-hour trial, “justice” was pronounced. Gutterer, who had not previously had a jail term, was sentenced to two months in prison for violating press laws. The court stated explicitly that it has pronounced this unusually harsh sentence to teach the young man how to be a decent citizen. Well, Gutterer went to the Frankfurt clink, but did not learn how to be a good citizen of the Weimar Republic.

I can no longer remember how often the Frankfurter Beobachter was banned before the Führer seized power. I only know that the subscribers, as long as they were party members, did not let any of these countless bans drive them away, but remained loyal even if their newspaper did not appear for days or weeks. [pp. 44-48]

Every Sunday, the movement’s leading figures in Frankfurt (Sprenger, Gemeinder, and Linder, along with the younger Gutterer, Heyse, Gert Rühle, Neef, etc.) spread out over the countryside under conditions that many of our current speakers can hardly imagine. If a speaker was lucky, there was someone there to lead the meeting. Sometimes he had an S.A. or S.S. man from Frankfurt along, sometimes he was his own meeting chairman. If the speaker was shouted down, if he attempted to talk over the screamer, then beer glasses started flying. Everything depended on his agility, since no one would lift a hand to help the hard-pressed speaker. Naturally, he had to pay travel costs out of his own pocket. If that was empty, as was so often the case, he had to borrow, and the borrowed money had to be paid back to the war chest. Despite all the difficulties, we succeeded in establishing individual local groups and agents across the area, so that during the course of 1927, we extended our net over the entire Gau, even if it was thin in places. [p. 49]

As I previously said, the Gauleiter ordered a near total concentration of our strengths internally for organizational reasons, but that does not mean that the public did not hear anything from us. That would not have agreed with our fighting nature. The comrades from the S.A. and S.S., along with the usual activists, turned more of their attention to our opponents. Since the ridiculous middle class parties had taken to refusing to allow National Socialists to speak during the discussion periods of their meetings, we appeared uninvited and quickly showed them that National Socialists could do something, even if they were not allowed to speak during discussion periods. When we broke up some fine bourgeois “democratic” black, red, blue, etc., tinged meeting, there would be loud laments the next day about our violence, crudeness, and unscrupulousness. It cannot be denied that not only our tone was raw and impolite, but that our actions were also crude, sometimes even violent. Aside from the fact that our tone had to be raw and blunt in order to be understood by the people, we had to do everything we could to stand out, even if in an unpleasant way, in a time when people wanted to ignore us. We were not made to suffer in silence, nor to capitulate to an apparently unavoidable fate with Olympian detachment.

After months of determined work, party comrade Sprenger had gradually dealt with the worst problems that prevailed when he became Gauleiter, and now decided on a major campaign in Frankfurt (M). First, he sent the reorganized S.A. and S.S. back into battle. Instantly, the opposing press stopped saying: “National Socialism is dead in Frankfurt (M)!” With pleasure, Jewish and other ink-pissers looked for everything that could hurt us in the eyes of good bourgeois citizens, giving columns of their papers to such things. From every side, cries reached the police complaining about the brown hordes, and the police, or more accurately the Marxist chief of police, listened all too gladly.

One Saturday, the S.A. planned a hiking trip in the city forest. They planned to gather at the hippodrome. About thirty S.A. men were waiting to leave when party comrade Aehender stepped off the streetcar with a bloody and wounded head. Of course, we hurried to help our heavily wounded comrade, whose brown shirt was soaked in blood, and told the conductor to stop the streetcar until the police could apprehend the culprits, who were still on the streetcar. As the conductor gave the signal to start moving, the streetcar was suddenly occupied by S.A. men from all sides, who prevented it from moving. The single policeman who appeared was not able to seize the culprits in all the confusion. The conductor attempted to escape once again to cover up the situation, but he was again hindered by the S.A. men. When the culprits were finally discovered, the S.A. marched back to the gathering place.

The howling police cars raced up, but not to arrest the devious culprits who had attacked party comrade Zehender in a cowardly way with heavy blows from a club and a stab through the lower jaw. Instead, they took the S.A. men to the police station. What was the title of one of the “cultural products” of that day? “The murdered is guilty, not the murderer!” Of course, nothing happened to our S.A. men as a result. But Monday’s newspapers! “Nazis storm a street car,” “Nazi hordes endanger a streetcar.” After the old motto “Say anything. Some of it will stick,” the journalists lied in the most creative manner. Those representatives of peace and order turned away from us in horror, those same people whose peace and order was being defended by our struggle.

About this time, a peculiar prophet appeared in our Gau capital who wanted to deal publicly with us National Socialists. “Publicly,” however, is a one-sided matter when one begins by saying: “I will not let him who I am dealing with respond in public.” But that is what stood on the posters of the Young German Order (Jungdeutscher Orden), the Jungdo for short. The posters announced that the master of this peculiar organization would deal with the National Socialists in the great hall of the city zoo. Master Mahraun brought his supporters from a hundred kilometers around to guard the meeting, and the hall was filled to the last seat, less by those who wished to benefit from Herr Mahraun’s wisdom, more by those who hoped to see a battle between the Jungbo and the Nazis. As we shouted louder and louder, demanding a chance to discuss, things broke loose. The learned gentleman must not have thought very much of his men, since he called for the police. They immediately appeared with billy clubs swinging. Party comrade Heyse, our appointed discussion speaker, and several comrades were driven into the corner and finally tossed out a window that was six feet above ground level by an overwhelming majority of Jungbo men. The wounded lay helpless in the snow with broken arms, legs, and other injuries, and called for help. Party comrades, trained emergency medics, were standing by, but the police prevented them from assisting the seriously wounded men. Only after a concerned old party member, Frau Mees, told the commanding officer just what she thought of him, were we graciously allowed to care for our wounded. Mahraun later sank so far as to merge the Democratic Party with the “German State Party.” However, the cloak of the Jungbo master could no longer conceal the flat feet of the State Party, and finally both vanished, the cloak and the State Party.

Late in the year, party comrade Sprenger thought the time had come to open the battle for Frankfurt. This would begin with a flourish: “Goebbels at the People’s Education Building!” To attempt to fill the large hall of the People’s Education Building was a big risk, but Sprenger was not cowed. “We’ll do it!” The tremendous success of the evening proved him right. Shortly after 8 p.m., the police had to close the hall, which was jammed to capacity. After a brief opening by party comrade Gemeinder, Dr. Goebbels began speaking. He who was not there can hardly imagine the powerful impact this master of the word had on the audience. But, after all, who had expected much from this previously unknown man? Just about everyone was hearing Dr. Goebbels for the first time. The audience hung on his every word. And how brilliantly the speaker dealt with several hecklers and the discussion speaker, the unavoidable Dr. Dang! Even so hard-boiled a character as Dr. Dang shrank before the power of the spirit behind Dr. Goebbels’s words.

Afterwards, the meeting continued on the streets in a spontaneous march against which even the police were helpless. “Heil Hitler!” roared through the streets. National Socialism was marching in Frankfurt! The crowd spread out in a firmly disciplined way, but there was a battle in the Fahrgasse. A Jew had, in cowardly fashion, beaten down an S.A. man from the rear. His shouts drew several comrades who succeeded in apprehending the fleeing culprit. The S.A. and S.S. men dealt with the Jewish creature in an exemplary fashion. They could have worked over his skull with his own club, but they did not. Instead, they applied it so thoroughly to his south pole that it was days before he could comfortably sit down again.

The Goebbels meeting was the talk of Frankfurt (M). Even the Frankfurter Zeitung, hardly our friend back then, could not avoid mentioning the fascination of the man Goebbels and his effect on the crowd. We did not stop. Wide circles of the Frankfurt population were now open to us. We had to keep moving. Night after night, the S.A. band marched through the streets of the city, advertising our idea. We even went to the politically notorious old city. The Red Front, however, was alert, and over a hundred Marxists followed the band, muttering as they went. The howling of the Internationale was overcome by the battle songs of the S.A. and S.S. At the Roß Market, the Reds plunged at the defenseless sixteen musicians shouting “Heil Moscow!” A student, party comrade Schmidt, was stabbed in the pelvis so badly that he immediately fell to the ground. The sight of the wounded comrade and rage at the treacherous attack got our S.A. men going. Within twenty minutes, using only their musical instruments and bare hands, they chased away a group five times their number. In the wild battle, which was also joined by bystanders, a Red Front member was stabbed in the belly by an unknown person. He died that night after an unsuccessful operation. Police investigations proved that National Socialists had nothing to do with the knife wound. Nevertheless, what the agitating newspapers wrote about us “murderers of workers” defies any description. We were powerless against such nonsense since the so-called bourgeois newspapers declined to carry our responses. This event clearly opened our eyes to the absolute necessity of our own newspaper.

We succeeded in holding another public meeting before the end of the year. Hundreds of us marched through the streets of Frankfurt behind Adolf Hitler’s banners of freedom. Battled-tested S.A. and S.S. men marched at the front, followed by what at the time was a large number of party members and supporters. Our success was even greater, since the march occurred on a Saturday afternoon. The streets and squares of the city thronged with people, who mostly looked in astonishment at the picture of a flawless, disciplined march, something they had not seen for a long time. Remarkably, the opponents left us almost alone. Here and there someone cursed us, but people had learned to respect us. The march ended at the Bismarck Memorial, where party comrade Gemeinder gave a passionate speech to the crowd of 600 to 700 people, and received enthusiastic applause. Shouts of “Heil” to Germany and to Adolf Hitler thundered over the broad square. Frankfurt had woken up! [pp. 51-55]

It hardly seems possible today that there was a time in Germany when Germans murdered Germans. But that is the terrible truth. In the area of our current Gau, two young, decent men were torn from our ranks in 1927, victims of political hate and blindness. The first to die a sacrificial death was 18-year-old S.A. man Wilhelm Wilhelmi in Nastätten. He had marched from Singhofen to Nastätten, where there was to be a meeting on “The true face of National Socialism,” with a Catholic priest, an Evangelical pastor, and a rabbi (!). To ensure that the population of Nastätten and the surroundings had an opportunity to hear a man who really knew something about National Socialism, namely the truth, party comrade Dr. Ley came from Cologne with several other party members. The numerically very weak S.A. from the area around Nastätten came as well. The two peculiar priests, who could not tell the difference between a pulpit and a political platform, failed to show up. The crowd grew increasingly restive. Party comrade Dr. Ley began speaking outdoors, and eloquently told the listening peoples comrades what National Socialism really wanted. The townspeople and farmers understood that they were exploited by the Jew, who was now attempting to exploit and suck dry the whole German people. The numerous Jews present, however, understood even better how to cause trouble by every available means. These provocations reached their high point as a Jew leaned out the window of a restaurant and injured the head of a passing S.A. man by hitting him with brass knuckles. As the S.A. men responded by attempting to haul the culprit out of the restaurant, the local cops guarded the door, swords in hand, to protect the Jewish crook. The police could not hold back the throng, so they withdrew inside. Even though he was not threatened or attacked, a policeman fired blindly into the crowd, tossed his pistol aside, and ran off. With a last cry, the 18-year-old Wilhelm Wilhelmi collapsed into the arms of his colleagues. A bullet in the head had ended his young life. Before entering his eternal rest, his last words were: “When do I get my uniform?” That was Germany in 1927: The young, thriving, proud German lad had to die so that the Jew, foreign in nationality and nature, could live!

Just a month later, Gau Hessen-Nassau has a second death to lay to the account of “Red Murder.” It was S.A. man Karl Ludwig, only a year older than his comrade Wilhelm Wilhelmi, who sacrificed his life in Wiesbaden for his faith in Germany. S.A. man Ludwig’s murder was of unbelievable cruelty and treachery. As a good comrade, Ludwig was staying with another sick S.A. man. In the middle of the night, both were lured out onto the street, where they were brutally attacked by seven or eight men. Karl Ludwig succeeded in rescuing his comrade from the crowd, but received such serious wounds in the process that he died painfully in the hospital the next day. The Marxist murderers had once again done good work to prove their “socialism.” By murdering the “capitalist” Karl Ludwig, they had taken a bit step forward toward a Marxist paradise. Is that really true? No, it is not. The murderers soiled their hands with the blood of a German worker, for Karl Ludwig was not one of the famed “300” whom the Jew Rathenau said ruled the world, only a normal, simple, but hardworking waiter. [pp. 57-59]

Our speakers were unceasingly back on the attack in 1928, party comrades Sprenger and Gemeinder most of all. The Reichstag election of 20 May was casting its shadow. Personal life had to take a back seat. Every evening, the slogan was: Fight! In view of the upcoming election, the countryside got special attention. We set foot in areas that had never even heard of Adolf Hitler’s freedom movement.

The fight for National Socialism was not always easy in the farming villages and small towns of Hesse-Nassau. Where today a National Socialist fortress stands, there was then not even a single representative. On 3 March, there was a meeting in Marxist-Jewish Usingen. Party comrade Gemeinder was the speaker, party comrade Heyse the chair, and one SS man to guard the meeting. The room was packed with Jews and Marxists. Given the terror, those who thought otherwise did not dare attend. The plan was to break up the meeting, but party comrade Gemeinder managed his remarks so carefully that everything went well. It was not pleasant for the speaker to stand in the middle of the boiling Red cauldron. One false word and one would have to reassemble one’s bones outside. Usingen has long since become one of Hitler’s cities, and the Jews who called the tune back then have disappeared. The next day at Rod an der Weil, things were the same. The Reichsbanner was there, but our fighting strength had increased to ten with the addition of nine new S.A. men. Thanks to the cleverness of our speaker and the work of Dr. Lommel in the background, the deceased Kreisleiter of Usingen, this meeting also ended peacefully, though without any particular success. Party comrade Stöhr, a Reichstag representative, spoke in February. At the beginning of March, the old populist National Socialist fighter Heinz Haake spoke in the Gau capital. He was a member of the state parliament and of the Reichstag, and for many years the only National Socialist member of the Prussian parliament. Both times, the Schützenhof and the large hall of the Volksbildungsheim were full.

Finding a hall was always a problem for us back then. The outrageous rents hampered our meeting activity. I have a document in front of me that shows how hard it was for our local group Greater Frankfurt (M) to hold large meetings back then, as money grew ever tighter.

The prices:

There were the usual chicaneries on top of that. Most of the time, we National Socialists could not get a hall at all. Often we lost a hall at the last moment due to Jewish terror.

One time, we stood with Dr. Goebbels outside the closed doors of the Volksbildungsheim. Another time, the Chamber of Commerce canceled the Börsensaal they had rented to us. Or the owner of the Sachsenhausen Saalbau closed his doors to us, and the owner of “Forrells Garden” on Adalbertstraße canceled our room, although it had been rented two weeks in advance, and although there was a signed contract. Even if someone canceled our meeting room or demanded outrageous sums for it, we held our meetings anyway. We simply went out on the street where peoples comrades heard us who would never have gone into one of our meetings.

On 15 March, Frankfurt saw a large number of our Brownshirts for the first time. We mobilized the groups from the surroundings and marched with 300 S.A. and S.S. men. That was a big thing at the time. Thousands of people in Frankfurt see, whether with joy or hatred, that young Germany is marching under Adolf Hitler’s banner. People packed the streets in the Old City and along the Zeil, waiting patiently for the march. Then it moved to the Zeil. Masses of people to the right, and masses of people to the left. Between them, the blood-red flag of the German freedom movement. The united revolutionary will expressed by these three groups of a hundred, marching in the same step, in the same brown shirts that wiped away all differences, with the same hope for the future shining in their eyes, all this impressed the watching people’s comrades. Even our opponents forgot to shout insults. Everyone was captivated by the swastika.

Now we kept moving. Each day there was a National Socialist mass meeting somewhere in the city. The meeting calendar in the Frankfurter Beobachter grew longer each day. Nearly every day, requests came in from the countryside: “Come here! We want to hear something about Hitler and his movement.” Our speakers, along with the S.A. and the S.S., were going somewhere nearly every day. After work, we dashed to the railway station, then marched for hours, returning late at night, since we could not fail to show up at the office.

Hard battles were also fought in the city council. Our four representatives assailed the Jew Landmann, thundered against the Jew Asch, and referred to aspects of May’s building projects. Sprenger spoke in Fraktur [the old-style German type font]. He could not be misunderstood, but the press said nothing. Gemeinder was no gentler. When necessary, he resorted to other means. Social Democrat Heise thus made the acquaintance of a glass of water.

For the first time, Brownshirts marched in Red Hanau. Sprenger held a subsequent meeting there, which was a great success. The first public meeting was held in Höchst. The Red press howled, but the only result is that the hall was packed. Gemeinder spoke and polished off three discussion speakers. The mob filled the streets outside. However, they did not dare to anything when faced with the S.A. Just outside Neid, the Reds threw stones at our trucks. Two S.A. men were slightly wounded.

Election activity — meetings — speeches — posters — leaflets — demonstrations! Who can keep them straight any longer! Two days before the Reichstag election (20 May 1923): Our ranks come together in the Gau capital. “Tighten the chin straps! S.A. march!” The band is in good form. Where is there another party with such leaders? The banners fly. Shouts of “Heil” from all sides. Thousands are standing at the Börsenplatz, cheering and raising their arms.

From meeting to meeting, from mass meeting to mass meeting, more and more and more the masses follow our flags. Gutterer and Gemeinder captivate the masses, earning storms of applause. No longer are hundreds marching. Now it is thousands. On election day, our Brown Shirts march through Frankfurt’s streets, urging people to vote. The election is over. At 7:30 p.m., the Flora Hall is packed. Hundreds have to be turned away. The first results! Do they give evidence of a dying party, as the Jewish journals have been writing? National Socialism lives! Three years after the party’s re-foundation, we have twelve fighters in the Reichstag. The fragmented völkisch groups, large and small — the famed völkisch fragmentation — has vanished. In their place, the united strength of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. In the Prussian parliament, we went from one seat to six, in Bavaria from six to nine. We got 13,020 votes in Frankfurt, as opposed to 4,637 in the previous election. We held our four seats in the city council. Our representatives were party comrades Sprenger, Gemeinder, Linder, and Schmitz. Election results in the countryside were sometimes splendid. In Dill County, we there the strongest party in six places: Eibelshausen, Langenaubach, Nieder-Roßbach, Ober-Roßbach, Offdilln, and Hirzenhain. In three, we had the absolute majority. The election results showed what energetic work could accomplish in the countryside.

During this period, another young German worker fell victim to the insanity and blindness of a hepped-up mob in the Hessian town of Pfungstadt. There was a meeting in Pfungstadt on 12 May 1928, after which the local group Pfungstadt of the NSDAP was founded. That evening, the 18-year-old typesetter Heinrich Kottmann, who previously had been very active as a leader of the evangelical youth movement, marched for the first time with the S.A. The SPD and KPD gathered in an effort to break up our meeting. A group of our people were driven into a dark side street, and attacked by opponents. Several S.A. and S.S. men were seriously wounded, among them Heinrich Kottmann. The badly injured men were taken to the doctor’s home. The opponents attempted to enter, and even attacked the medics who brought the dying Heinrich Kottmann to the hospital. 12 May 1928 was Heinrich Kottmann’s eighteenth birthday. He died on 13 May from the knife wound he had in his back. [pp. 61-65]

[The following section reproduces a 1 November 1928 newsletter to party members]

National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Copy!)Frankfurt (M), 1 November 1928

1. General

Local Group Frankfurt (M) intends to increase efforts to reach the public in the month of November. Unfortunately, the time frame for the meetings does not allow time for a membership meeting to plan for them. Members are therefore asked through this means to use every possible allowable means to support the local group’s leadership. The meeting plan will appear in the Frankfurter Beobachter of 2 November 1928. Note that there are still some members who do not subscribe to the Frankfurter Beobachter.

On 11 November, there will be the first meeting of Gau representatives, in conjunction with large public meetings. It is possible that Reichstag representative Gregor Strasser, appointed organization leader by the Reichsleitung. will appear. This alone is enough to make it clear that the local group has to demonstrate its inner and outer strength. The month of November belongs to the movement.

2. Propaganda

The local group’s leadership in no way underestimates the personal promotional activity of individual members. We know the efforts of individual party comrades are to thank for the significant position that our movement was won. However, all those efforts can be destroyed when some party comrades who lack even a basic understanding of our program still dare to discuss the movement. Recently, we have repeatedly seen a few party comrades say the most ridiculous things. For example: A party comrade told an opponent that “National Socialism” and communism were entirely different. Another came along and talked to the first party comrade about things that he did not understand.

He said:

“National Socialism is exactly the same as communism, except that we want to carry out our thinking on nationalist foundations!”

This example is typical. It is one of many. We have serious concerns about such propaganda. The leadership thinks as follows:

a) In the future, avoid debates in front of the Böhle Bookstore, which are usually begun by provocateurs who want to hurt the proprietor.

b) We cannot prevent the unemployed, etc., from gathering and debating. Party comrades, however, should keep a careful eye and ear open for those debaters who are not out to help the movement, but rather to spout nonsense that they themselves generally do not believe.

3. Public mass meetings and other meetings:

Our membership things that the admission fees for our events are too high. Here are the facts. A meeting in the Volksbildungsheim require the following costs:

| a) Rent, lighting, heating | 200 RM |

| b) Posters (84 x 120 centimeters) | 80 RM |

| c) Charge for hanging 200 posters (600 available locations) | 100 RM |

| d) 3000 leaflets | 40 RM |

| e) Banners to carry | 30 RM |

| f) Other expenses, e.g. speaker honoraria | 225 RM |

|

475 RM |

Obviously, anyone can see that these can only be covered by admission fees, since, “thank God,” we have no rich people to pay them. The receipts, in contrast, are:

| a) 600 tickets at 50 pfennig each | 300 RM |

| b) 300 tickets at 30 pfennig each | 90 RM |

| 390 RM |

Everything we took in with more attendees, in short, was just enough to cover the expenses, which were sometimes even higher. So please do not complain about high admission fees, but instead work to get even more people to attend. Our previous successful meetings were because we were able to get others to attend.

With regards to the local group’s propaganda marches, I have the following to say: It will not do for male party comrades to stand and watch on the sidewalks instead of donning an S.A. uniform and marching along. In most cases, the police will see than as opponents and force them into side streets. Join the ranks, and he who is able should not be shy about putting on the brown shirt.

4. Neighborhood groups and agents:

a) Membership dues

Except for a few party comrades, dues payment has significantly improved. Each fighter knows that one needs ammunition for the battle. Therefore, the fighters of a political movement sacrifice with money. Hopefully, each party comrade knows that those who do not fulfill their duties will not be welcome in the Hitler movement.

b) The agents in city neighborhoods are my representatives. I hope that no one will refuse to support them.

5. Business office:

The Gauleitung, the local group, and the “F.B.” have so far shared one room as an office. That cannot continue much longer. A larger office will cost us the same as the present office, so we intend when feasible to enlarge our space. It should be noted, however, that these plans cannot yet be discussed in public. The local group leadership still needs a desk, a storage cabinet, and chairs. These, of course, should not be luxurious, but rather office furniture. Above all we need a typewriter, which even today I unfortunately have to do without.

6. Collections and contributions:

I have already noted that the local group cannot survive without contributions, even pfennigs for the “battle treasury.” As always, only those are authorized to collect donations who have a list signed by me and stamped with the local group seal. Currently, the following lists are circulating:

a) a collection by the women’s group for Christmas gifts,

b) a collection for a dignified memorial ceremony for the dead,

c) a collection to support a good band.

I also ask you to support me personally by selling the “Battle Certificate” at all coming meetings, since the sooner the 2,000 certificates are sold, the more quickly the daily and hourly wish of party comrades for a “Hitler Meeting” can be met. Our Führer can and will speak here only if Frankfurt (M) can hold a meeting with its own resources in a financially and organizationally effective manner.

So get to work!

7. Final remarks:

As one can see, strong conflicts are going on in every party, mostly of a personal nature. Such things may not happen in our movement. Anyone who nonetheless makes a stink, or even dares to attack or insult the Führer, must expect to lose our friendship. We always think of one goal, that we want to free Germany, our beloved fatherland, and the German people. First of all, we know our duty, and only secondly, our rights. In our movement, the slogan, whether for top leaders or for regular party comrades, is:

“Everything for my people, nothing for me!”

Heil! Gemeinder

The others could not stop our advance. Our activity shook the dozing politicians of every party. The brown columns doubtless made an impression even on our opponents. The familiar “favorable” wind blew us, for example, a secret newsletter from the Reichsbanner, in which the National Socialists were presented as models for comrades in the Reichsbanner. The Republican front could no longer sleep. On 11 August, therefore, there was a “huge march” by the Reichsbanner. The Jewish press presented it as a powerful throng of one hundred thousand that marched through Frankfurt for two hours. It is clear, however, that a hundred thousand men cannot march past within two hours. According to more precise calculations, it could not have been over 13,000, and they did not leave the best impression behind. There were probably thousands of curious people along the street, but there was nothing of the enthusiasm that would be seen, for example, in our march in Nuremberg a year later.

One minor episode should not be forgotten. On the evening before the march of the “hundred thousand,” hundreds of Reichsbanner men streamed out from the arriving trains, and marched in small groups to their quarters. Suddenly, one heard loud singing, which certainly could not have come from the thirsty Reichsbanner throats. In tight march formation, 120 to 150 uniformed S.A. men coming from a roll call turned onto the Kaiserstraße. Everyone was stunned. Unconcerned, the Brownshirts marched with exemplary order past the Reichsbanner men. Startled, the Reds let our people go past. The drums quieted down, and swastika songs dominated the street. [pp. 67-71]

We ended the fighting year 1928 with a powerful mass meeting. Party comrade Goebbels spoke. Just before the year’s end, we opened the battle for Frankfurt with the Gauleiter from Berlin. Month after month, our movement’s most prominent speakers appeared in the Volksbildungsheim. To finish the year, we hold our meeting for the first time in the great hall at the zoo! Dr. Goebbels’s moving speech was heard by a breathless crowd, and greeted with a true storm of applause. After a march of the unemployed the evening before, a worked (unemployed and the father of four) was attacked by Reds and other members of a criminal mob as he walked home alone, and seriously injured by a stab in the head. As passers by tried to help, the cowardly mob fled. The mob was afraid of the anger of the victorious swastika, and attempted to show its limited bravery against a single Brownshirt. After the Goebbels’s meeting, too, the red beast lurked in dark corners and attempted to attack several individual meeting attendees. They did not succeed very well that night. Our S.A. was at its posts, and our brown youth gave some things to think about. [pp. 73-74]

In the truest sense of the word, 1929 stood under this slogan. I do not want to hurt anyone’s feelings, but I sometimes have to smile when I visit someone in a quiet, comfortable, well-equipped office and see a poster on the wall announcing “The battle continues,” naturally in elegant script, and a fine frame, covered by glass. Back then, it still meant something. The new year was filled with battle from its beginning. And it ended the same way, as did the year following.

After the organization had been built up in 1928 to a reasonably decent degree, the time had come to put our full efforts into propaganda. I present but a few dates from 1929 to show what the leadership had to do:

| 2.1.1929 | Leadership conference (Gemeinder) |

| 3.1.1929 | Leadership conference (Gemeinder) |

| 9.1.1929 | Meeting with neighborhood agents (Gemeinder) |

| 11.1.1929 | Public discussion evening in the Florasaal |

| 18.1.1929 | Public meeting with party comrade Münchmeyer |

| 21.1.1929 | Section meeting Bockenheim, Rödelheim, Hausen |

| 22.1.1929 | Section meeting Sachsenhausen, Niederrad, Gallus |

| 23.1.1929 | Section meeting Nordend, Eschersheim, Heddernheim |

| 24.1.1928 | Section meeting Inennstadt, Ostend, Bornheim, Seckbach |

| 28.1.1929 | Public women’s meeting (Elsbeth Zander) |

| 31.1.1929 | Leadership meeting with Gauleiter Sprenger |

| 1.2.1929 | Public meeting in the Volksbildungsheim |

That is only a small part of the propaganda activity for a single month. Beyond that, there was, of course, always the propaganda activities of the S.A. and S.S., which distributed leaflets and newspapers inside and outside of Frankfurt.

We naturally tried to vary the speakers for our mass meetings, and securing speakers always gave us headaches. I remember today how happy I was when I helped to get party comrade Count Reventlow to speak, since Gauleiter Sprenger wanted to get him as a speaker. I had gone to a Gauleiter meeting in Munich with our Gauleiter. I spotted party comrade Count Reventlow and shadowed him. When opportunity arose, I went up to the count and said: “Party comrade Count Reventlow, you should have spoken in Frankfurt (M) a long time ago, and I am sure you will enjoy it. Give me a date when you can come to Frankfurt.” “I should speak in Frankfurt?” he replied in astonishment. “Who is inviting me?” I explained to him that I was the business manager of local group Greater Frankfurt (M), and that I was there along with Gauleiter Sprenger, and that he could speak directly with party comrade Sprenger himself, which quickly happened.

Now it was the Gauleiter who was surprised, since he had no idea of what I was doing. But he pulled himself together quickly, as always, and set a date with party comrade Count Reventlow. [pp. 75-76]

[The next chapters cover 1930, the year of the Nazi electoral breakthrough. Two excerpts.]

The fight became ever stormier and exhausting during this period. On 4 September there was a women’s meeting in Bechtheim. During the evening of 5 September and into the next morning I distributed leaflets in the area and pasted posters everywhere I could, constantly followed by spies and provocateurs. On 7 September I participated in a lively propaganda march in the area around Osthofen, followed by a meeting in Osthofen on the 8th. On 9 September I was part of the meeting hall guard in a meeting with party comrade Kraft, Bensheim, and in Bechtheim. The next day was Groß-Gerau, where a general reckoning was planned. It turned into one of the stormiest meetings I was ever at. We had 32 men, among them three Hitler Youth, in a covered truck. As we got to Groß-Gerau, the city streets were entirely empty. It was the calm before the storm. After undergoing a thorough search for weapons at the meeting hall, we marched in to meet a deafening clamor. Despite the disharmonious situation and despite sharp exchanges between our speaker and two discussion speakers, we succeeded in holding the meeting. The opponents left with shouts of rage, but only to find favorable positions outside the hall. As we reached the street and prepared to march off, we believed that it was all over. With animal growls, about 300 men attacked us. The first of them swung at our faces with their shoulder straps. They must have had great respect for us, though, for despite their overwhelming numbers we drove them back. We were followed to the next village. Stones, clubs, and knives flew toward our ranks, but the heroes lacked the courage for a frontal assault. Every comrade suffered more or less severe wounds, but no one let it be known. When an opponent got too close, a blow came from our ranks. With my shoulder strap in one hand and a table knife in the other, I marched at the front and led the troop to Büttelsborn, where we could take a break and bandage up our wounds. Late at night we climbed into our truck and took a long detour through Worms, since the ferryman at the Rhine was long since in bed. About 6 a.m. we got home, dead tired and worn out.

The next two days I was back in Osthofen, on the 11th to guard a meeting and on 12 September as bodyguard for party comrade d’Angelo, who asked for our help after our S.A. comrades had been attacked while distributing leaflets. S.S. men Müller, Schmitt, and I marched at top speed to Osthofen. Halfway there we heard about eight shots, which encouraged us to move even faster. Near the city pharmacy were several idle chaps who pointed the way to the battleground. Along the way we met our old party comrade Spangenmacher who was bleeding heavily from a bullet wound in the head and wanted to see a doctor. We put him between us and got to the next corner, where ten or twelve men attacked us with clubs, steel rods, and iron bars. One of the culprits even had an ax. In the middle of the battle the police came along and searched us for weapons.

The battle in Osthofen continued on 13 September with a meeting featuring party comrade Geyser-Fett. Although the opponent brought in reinforcements from Worms (Rhine), we carried the meeting through. After the events of the past few days, however, no one dared attack us. The heroes restricted themselves to infernal howls as we marched out. During the night party comrade and S.S. man Lottermann from Osthofen was attacked and severely wounded, spending a long time in the hospital. We were unable to help party comrade Lotterman, since at the time of the attack we had long since marched out of Osthofen . [pp. 101-103]

The Frankfurt Nazis, in Munich for the dedication of the new party building, ask Hitler to speak.]

The Führer accepted Gauleiter Sprenger’s invitation to speak in Frankfurt am M. Half seriously, half in jest, the Führer said: “Sprenger, if things do not work out in Frankfurt, it will cost you your head.” The Gauleiter instantly replied: “In that case, I am ready to put my head on the chopping block.”

The Führer specified the beginning of August for the mass meeting. We rushed to Frankfurt a. M. the next day to give the news to our comrades in the Gau office. Of course, as soon as the news got out that the Führer would speak in Frankfurt a. M., the Jews and their Jewish lackeys did everything they could to make the meeting impossible. The meeting was first scheduled for 1 August, but the gentlemen Communists were holding an “anti-war day” in Frankfurt a. M. When we proposed 2 August, a planned Reichsbanner [the SPD paramilitary organization] march provided welcome opportunity for a second ban. One can see that our initial fears at holding a mass meeting with the Führer were hardly exaggerated. We did obtain permission for 3 August, but that came with a ban on marching. After bureaucratic chicaneries were finished, the unofficial defenses moved against us. During the night before 3 August Reichsbanner and Communist forces went about plastering our posters with a note saying "Speaker canceled.” Our own forces were active the whole night, too, either to remove the stickers or put up new posters. Clearly things came to physical blows, but we could not respond too forcefully because that would have given a welcome excuse to ban the meeting. Thousands of tickets were sold before the meeting, and on the morning of 3 August by 9 a.m. masses of people’s comrades came to the hall to buy a ticket. From everywhere in our Gau, from Hesse, even from the Pfalz, German men and women rushed to Frankfurt by train, by auto, on bicycles and in trucks. The enormous hall opened at 5 p.m., and thousands and thousands of people streamed in. At 8 p.m. the hall was filled to capacity and the police blocked further entrance. Now, one needs to know that even today the Frankfurt Festhalle is one of the largest enclosed halls in Europe with a capacity of 18,000. However, the first Hitler meeting packed 20,000 in. 5,000 to 6,000 people’s comrades could not be admitted and had to listen to the Führer of the Germans over loudspeakers outside. Since then I have experienced many mass meetings of unprecedented size in the Frankfurt Festhalle, but the Führer’s enormous mass meeting in Frankfurt remains unforgettable in my mind. People were literally hanging from the rafters. The feverishly excited crowd roared, mixed with the resounding old familiar marches. The enormous dome was filled with the flags of the coming Reich, their red color shining in the light of thousands of spotlights. Now came the standards and waving flags of 2500 marching S.A. and S.S. men. Their firm step and powerful march music were drowned out by the shouts and heils of 20,000. The S.A. and S.S. took their positions. In the grip of excitement, the crowd quieted. Then the march now familiar to the whole world began to play. Simultaneously, a hurricane of jubilation and stormy enthusiasm erupted, reaching its epitome in tidal waves of cheers as the Führer stepped onto the stage. He stood there modestly and simply, his gleaming eyes filled with joy as he surveyed the huge space. Minute after minute passed before the joy and enthusiasm subsided. Finally things quieted down and a voice rang through the huge hall like a bell, planting hope, faith, and enthusiasm in the hearts of the breathlessly listening crowd. Cheers broke out repeatedly when the Führer expressed a particularly striking thought, thereby clothing in words what thousands sensed and felt, but could not be expressed either by themselves or others. Still today I hear the Führer’s words which have now taken form and become history: “A people can accomplish great things if it has a capable leadership. and this leadership must be brilliant, wise, capable of action, brave, and—if necessary—audacious. If all of Germany thinks democratically, as the Berliner Tageblatt or the Frankfurter Zeitung desire, the German people will no longer exist in forty years. But if all Germany thinks in a National Socialist way, after ten years it will no longer be enslaved!” Reporters from leading domestic and international papers were present, even a representative from the Foreign Office in Berlin. I wonder if the gentlemen remember those prophetic words today? August 1940, when I was writing these words, would have been the right time, exactly ten years later, to remember what the Führer said in the Frankfurt a. M. Festhalle. [pp. 107-109]

With the breakthrough of 30 January 1933, the great battle for Germany that had raged for fourteen years seemed at an end. With steadfast loyalty and a unique willingness to sacrifice, the Führer’s political soldiers had stood at his side during the long and difficult battles. Adolf Hitler himself gave his oldest followers from the early days of the movement the honorary name “old guard.” Those who had joined the movement during the struggle for power rightly call themselves “old fighters.” And not the worst of those in the ranks of the old guard and old fighters, those who carried the swastika banner to victory, came from the former royal city on the Main River, the German Rhine, and the land of the Hessians. These were men with strong hearts and iron and unbending wills who transformed the faith that can move mountains into action. In the worst times and amidst the most painful losses, they believed in Germany and in Adolf Hitler. For the sake of their faith they endured scorn, mockery, hatred, and oppression, becoming even more fanatical and stronger in their faith. They came to see the Führer’s greatness not through the outward success of the movement’s final victory, but rather through Germany’s need, and to a large degree because of the sacrificial death of sixteen men before the Feldherrnhalle in Munich.

I greet the old fighters and comrades in Gau Hessen-Nassau. As you read this book, let the memories of that hard but proud period of struggle come to life for you again. As some read this story, may they think back and say: That is how we fought! [p. 164]

Last edited 6 September 2025

Page copyright © 2007 by Randall Bytwerk. No unauthorized reproduction. My e-mail address is available on the FAQ page.

Go to the German Propaganda Home Page.