Background: On 31 May 1942 the British conducted a large bombing attack on Cologne, the largest attack to date and an example of what was to come. This widely-circulated pamphlet appeared in September or October of 1942, some months later. It suggests that British bombing, though damaging, would never break German morale. It also makes the interesting claim that the German Luftwaffe had avoided civilian targets, ignoring German attacks on Rotterdam and British cities.

The author was a rather active Nazi propagandist. He was a Reichsredner, one of the party’s elite speakers, a radio director in Cologne, and later director of foreign broadcasting. He was also an SS member.

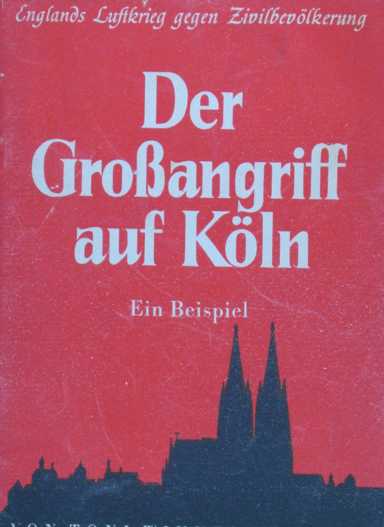

The source: Toni Winkelnkemper, Der Großangriff auf Köln. Ein Beispiel (Berlin: Franz Eher, 1942).

The Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht announced on 31 May 1942:

The Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht announced on 31 May 1942:

“British bombers conducted a terror bombing of Cologne’s center over the past night, causing great damage through bombs and fires, particularly in residential areas and to public buildings, including for example three churches and two hospitals. The British air force suffered heavy losses in these attacks on the civilian population. Night fighters and flak shot down 36 of the attacking bombers. A further bomber was brought down by coastal artillery.”

It is the night of 30-31 May 1942. As so often before, the air raid alarms sound at midnight in Cologne. As the first bombs fall at 12:15 a.m., everyone believes that his neighborhood is the target. No one yet knows that the British are making a major attack and are attempting to destroy the residential areas of the whole city. In the glare of searchlights of Cologne’s defensive ring, the first enemy planes break through the evening clouds.

The flak begins to fire. The first British attack wave goes after flak positions, using dive bombers with bombs and machine guns. Some hit their targets. There are dead and wounded, but the light and heavy guns continue firing, shot after shot. Amidst the roar of flak shells, there are the sounds of exploding heavy bombers and the crackling hail of falling incendiary bombs and clusters. The first flames ignite. Flames shoot from apartment buildings and department stores, swelling, blazing flames that greedily spread. The dark city is brightly illumined by the red glow of widespread fires.

In steady new waves, the British openly ignore military targets and aim for the city’s residential districts. The insect-like buzzing of their airplanes sounds ever more menacing, and the dreadful sounds of exploding shells and detonating bombs, mixed with the chattering of machine guns aimed at the civilian population, grows ever louder.

For over an hour and a half, a terrible hail of hundreds of bombs and incendiary canisters, over a dozen blockbusters and over a hundred thousand incendiary bombs fall on Cologne’s residential districts. Apartment buildings and multi-storied buildings burn, collapsing with loud crashes.

Only after 2:30 a.m. do these terrible sounds begin to quiet down, and one hears only the crackling of greedy flames and the sounds of falling ceilings and collapsing walls. At the dawn of a rainy morning, the whole city is covered with clouds of mist and smoke, interrupted by raging flames. Hardly a neighborhood of Cologne is untouched, nor are churches, museums, schools, hospitals and other community buildings spared. The “major attack” on the open city of Cologne, which the British call

“The largest air attack in history”

is aimed only and exclusively at the civilian population.

One does not need to conceal the extent of the damage. The civilian population suffered great loss of life and property. Several hundred died this night. Thousands more were wounded to a greater or lesser degree, and tens of thousands became homeless.

Irreplaceable treasures in Cologne’s center were forever destroyed. Artistically valuable public buildings and dwellings which were under landmark preservation vanished from the scene, such as the Vanderstein-Bellen building on the Haymarket, the Guild House Unter Goldschmied, the Faßbinderzunft House on the Filzengraben, the Temple House on the Rheingasse, the Overstolzen House on Eigelstein, the blocks around the Old Market, the Glockenstraße, In der Höhe, am Lichthof, the Marienplatz, the Straßburger and the Salzgasse, the Mathias-Straße and Weberstraße.

21 churches were heavily damaged, most completely destroyed. They were among the most important treasures of German architecture. Among them were three of the oldest and most artistically significant churches in Germany: “Maria im Kapitol,” “St. Aposteln,” and “St. Gereon.”

The commercial sector had only minor and temporary damage. There was no serious damage. From the type and nature of the attack, there is no doubt that it was directed at the civilian population, not military targets. Even the English press, which is never reluctant to invent successes, did not make an attempt to claim the terror attack on Cologne was a military success.

The negative military results of this attack are clear and obvious. The German defenses were alert and, as always, at their posts.

“The British aircraft involved” — the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht added on 2 June — “attacked in several waves. According to information so far, 37 fell victim to the effective German defense. Among the types of aircraft shot down were Vickers-Wellington, Whitley, Hampden, Blenheim aircraft, and also several four-engine bombers. The crews generally were not able to use their parachutes. Along with the extraordinarily heavy loss of 37 aircraft, the British air force also lost over 200 men. A London news agency reported on Sunday that 44 planes from yesterday’s attack on Cologne had not returned.”

44 British bombers failed to return from their attack on Cologne’s residential districts. That is an extraordinarily high rate of loss, even measured against the results of the attack. British air experts have recognized this, and they have — more or less clearly— let the public know their concerns.

In Germany no one thinks that these voices have any particular significance. Nor does anyone think that such considerations will stop Churchill from again sending bombers into the fire of German defenses to sacrifice his best crews for an illusion. This man’s long career of failures has proven that he holds to his mistakes with remarkable loyalty and is not able to learn from experience. The continuance of terror attacks on other German cities confirms our opinion. Still, it is interesting to know that doubts occasionally surface even on the enemy’s side as to the “profitability” of such major attacks. The military expert of the Daily Express wrote on 25 July 1942:

“The effort it takes to mount such huge attacks is greater than England can currently sustain.”

In a following sentence, he points out to Churchill that it would perhaps be better to use the planes in strategically important areas rather than sending them against German women and children.

Major Oliver Stuart, an English air force expert, make the point even more clearly in the African Service of London radio on 1 June 1942. There is some doubt, he said, as to whether Great Britain will be able in the near future to build the number of night bombers necessary to replace an average loss of 44 planes in each attack, along with the unavoidable losses through accidents. If 44 planes are lost each night, that means 1320 a month, and that figure only includes night bombers based in England. This figure does not include British aircraft losses in the war’s other theaters. Major Stuart went on to say that it required no special intelligence to realize that England’s industry could not build airplanes fast enough to cover the British air force’s losses. His comments can be understood only when one realizes that Oliver Stuart views the terror attacks on residential districts as a “side show” for the British air force, having a strategic purpose only in that sense. In fact, however — as we know from British sources — the planning and carrying out of such major attacks on German cities requires extraordinary effort. One reads in the English press that each and every available night bomber had to be used for the attack on Cologne. That is certainly an exaggeration, but still enlightening. A dispatch from the International News Service (INS) sounds more reliable when it claims that planes left from more than sixty airfields. The attack involved several thousand crew members and a hundred thousand ground personnel.

Thoughtful statements by experts could not stop Churchill from the politically necessary shouts of triumph. He held stubbornly to the belief that destroyed buildings meant that German morale had also been destroyed, and that German’s will to victory had also been broken. Besides, Comrade Molotov, Stalin’s ambassador was in London at the time. Churchill needed to impress him with an apparent military “success” to show the strength of the British air force to persuade him to accept an urgently hoped for military agreement. Everything he had to say about the terror attack on Cologne was cheap bluff and cynical calculation.

On the night of the attack, Churchill sent the leaders of the British air force a congratulatory telegram in which he expressed his thanks and appreciation for this cowardly attack, and went on to say that the terror attack on Cologne must serve “as a model in every regard.” Two days later, after the attack on Duisburg on 1 June, the commander of the British bomber command received a telegram from Air Minister Sinclair that said:

“I send my congratulations for the success of the attack on Cologne and the Ruhr area. The enemy has been bit by a double blow, which is the result of months of patient and hard work.”

What the press and radio in England and the USA reported, aside from the more thoughtful statements cited above, certainly put great trust in the gullibility of their readers and listeners. These papers and stations worked hard to outdo each other with every increasing figures about the size of the British “success” and of the German losses. Among the more modest was the claim that Cologne has suffered 20,000 dead and 60,000 wounded. London radio cited American sources on 2 June claiming that 60 percent of Cologne’s population had to be evacuated — which would be 480,000 people. There were more accounts along these lines. The number of planes involved in the attack on Cologne also grew from day to day — at the same rate, by the way, as reasonable Englishmen realized the meaning of 44 lost aircraft. That is an old and favorite trick. The percentage of aircraft lost becomes smaller and less alarming as one adds to the number of planes supposedly involved.

With such tricks, the enemy’s press and radio attempted to distract the world public from the fundamental fact that this costly terror attack completely failed to reach its goal. The attack on the strength of character, the courage, the endurance and the morale of Cologne’s population failed utterly. All the other terror attacks on cities and towns in the Reich have had the same result. When therefore the British news agency Exchange Telegraph wrote on 1 June 1942 after the attack on Cologne:

“The bombing of Cologne is a decisive turning point in the war —”

It is perhaps right, as Churchill’s last remaining card has been wasted. After failing everywhere else in the war, his only hope was to speculate on a weakening of the German civilian population under the blows of his terror.

We have come to know these blows, and we do not want to minimize them. But we have also come to know the German population’s hardness, its determination, and willingness to sacrifice. Its attitude, its manly endurance under the hard blows of fate, actually has led to a turning point in the war — a greater one than many realize. Friend and foe alike know that now and for all times, the German civilian theater is unbreakable. This people is stronger than Churchill’s terror!

A fundamental principle of international law that all civilized nations have solemnly affirmed is that wars are fought between armed forces, and that defenseless civilians, above all women and children, should be safe from enemy action.

Great Britain’s policy has always been to affirm the slogans of international law and humanity at every opportunity — but to trample on them whenever necessary. The world is well aware of the terrible brutality with which the British so often in their history have acted against innocent women and children. Every German remembers the hunger blockade the British conducted against the German civilian population during the World War of 1914-1918, mocking international law.

Every new weapon humanity invents brings new possibilities for misuse. That is particularly true for the air force. It stretches the arm of the fighting forces far beyond the front into the enemy’s peaceful hinterland, reaching them with death-dealing weapons. We Germans who lived along the border during the World War 1914-1918 already had a bitter taste of that.

In the years following the World War — at least in enemy countries — there was a dynamic development of long range bombers that led to their present form. Voices calling for humanitarian limitations of aerial warfare were not silent. The British above all made fine-sounding statements about humanitarian restrictions. But only Adolf Hitler made really practical suggestions for disarmament and for more humanitarian warfare. His proposals were always ignored.

“I do not want to wage war against women and children.” Adolf Hitler

Despite constant disregard for his disarmament proposals, Adolf Hitler acted according to the demands of humanity at the moment of decision. As our army began its revenge against the blinded Polish pseudo-state on 1 September 1939, the German Luftwaffe received particularly strict instructions with regard to its choice of targets.

As the Führer said in his speech to the Reichstag on 1 September 1939:

“I do not want to wage war against women and children. I have given my Luftwaffe the order to limit their attacks to military targets.”

The world knows that the Führer held to his principle. On 19 September 1939, speaking in the Artus Court in the liberated city of Danzig, he repeated the statement:

“I have given the German Luftwaffe the order to fight this war humanely, which means that they will attack only fighting troops.”

These words display the deep sense of responsibility — from the German standpoint — that each head of state and military leader must have who controls such a wide-reaching, terrible weapon, and who can decide in which ways to use it. Events have shown that only a true leading personality is able to feel this responsibility and make the corresponding moral decisions. Only one person can be responsible. A parliamentary system lacks conscience. The majority rules, which eliminates any feeling of responsibility.

England has always misused weapons in which it was superior to other peoples — naval power, for example. That was clear at every stage in the growth of its empire. England hoped once more to reach its goals by a hunger blockade. The Führer characterized this characteristic British attitude in the same speech in Danzig:

“England has already begun the war against women and children with lies and hypocrisy. It has a weapon it believes unassailable, namely sea power, and says: Since we ourselves cannot be attacked with this weapon, we are justified in using it, if necessary, to fight not only the women and children of our enemy, but also those of neutral nations. One should not deceive oneself! The time could soon come when we too use a weapon that cannot be used against us. One hopes others then do not suddenly remember the principles of humanity and the impossibility of waging war against women and children. We Germans do not do that. It is not our way.”

How easy it would have been for National Socialist Germany to misuse its superiority in the air just as Great Britain has always done at sea. But in Poland, Adolf Hitler gave the world proof of his military leadership. The Luftwaffe followed his orders and attacked only military targets.

It was irresponsible of Poland’s leaders to declare Warsaw a fortified city, overflowing with people as it was. Machine guns and artillery were set behind the moral protection of women and children. That was a disgusting mockery of the decent German style of combat. The Führer left no doubt that his knightly approach presumed reciprocity, and that it could not be misused by one side. In his speech in Danzig before the storming of Warsaw, he said:

“I have given the order in this campaign to spare cities whenever possible. We have held to this principle. In those areas where insane, crazy or criminal elements did not resist, not a window has been broken. In Krakow, not a bomb fell inside the city, save for the railway station and airfield, which are military objects. But if one fights in every street and building in Warsaw, the war will naturally engulf the whole city.”

And in his major speech to the Reichstag on 6 October 1939, the Führer reaffirmed once more:

“Out of pity for women and children, I have offered the rulers of Warsaw the opportunity to at least allow the civilian population to leave the city. I declared a truce, guaranteed the necessary escape routes, and we all waited in vain for a parliamentarian, just as we waited in vain at the end of August for a Polish negotiator. The proud Polish city commander did not even grace us with an answer. I extended the truce, and ordered our bombers and heavy artillery to attack only clear military targets. I repeated my offer, but it was in vain! I therefore offered not to attack an entire section of the city, Praga, reserving it for the civilian population to give them the opportunity to go there. This proposal, too, met with Polish contempt.”

The Führer knew the misery that he wanted to spare women and children. Unlike his counterparts in London, Washington and Paris, the musketeer of the World War, who today commands the strongest military force in the world, learned the horrors of war in his four years at the front. In the middle of a victorious war and fully aware of his military might, he did all he could to humanize warfare. In his Reichstag speech on 6 October 1939 he said:

“The most important precondition for a true flowering of the European, as well as the non-European, economy is the establishment of a guaranteed peace and a sense of security for the individual peoples. This necessary sense of security depends on clarifying the use and fields for certain modern weapons that are able to strike at the heart of the individual peoples, thereby creating a lasting sense of insecurity. I have made proposals in this regard in my previous speeches to the Reichstag. They were rejected then — presumably because they came from me. Yet I believe that a feeling of national security in Europe will return only when there are clear international agreements and obligations as to the concept of permitted and banned weapon usage.

The Geneva Convention, at least among civilized states, forbade the killing of the wounded, the mistreatment of prisoners, attacks on civilians, etc. Over the course of time, these principles came to have general acceptance. So also we must agree on the use of aerial force, the use of case, etc. of U-boats, and also guerilla warfare, so that war will not be waged against women and children, or against any civilians. The banning of certain conduct will lead to the elimination of weapons thereby rendered useless. During the war with Poland, I have taken care that the Luftwaffe attacked only so-called military targets, or was used only when there was active resistance at a certain point.”

The Luftwaffe was at the center of the discussions and predictions of the experts of every country during the fall weeks of 1939. The evaluation of the air force as a factor in military leadership, the reasons and counter-reasons for its importance in the war, these were everywhere discussed — everywhere but in Germany. Here we did not discuss, we acted. The Führer’s military genius had long-since recognized the role of the air force in modern warfare, along with its use in conjunction with other weapons. He had taken the appropriate steps. The Führer knew that a single weapon, even one as useful as the air force, would never be sufficient to decide a war. He always built his strategic plans on the basis of carefully calculated cooperation of the military branches and their various weapons. A good example, and a model for the world, is the Stuka (dive bomber), which distinguishes itself from all other aircraft types by its almost mathematical accuracy. It is suited as no other aircraft for attacks on military targets, providing the greatest possible protection for non-military targets. This alone proves the purely military nature of the German Luftwaffe.

The British are different. Their air force from the beginning adopted the methods of British warfare, namely the involvement of the civilian population in military conflict, be it through subversive propaganda or bloody terror — through leaflets or through bombs. During the first months of the war, its air force dropped remarkably foolish leaflets on German cities from great heights. Such a naive attack on the civilian population was more in line with their nature than a military attack, say against the German West Wall.

He who knows Great Britain’s history knows that the whip follows the candy, the bomb the leaflet. In September 1924, Mr. Winston Churchill published an article in Pall Mall Magazine that recognized with cynical openness that air terror against women and children was the most effective method of military leadership.

Mr. Churchill wrote:

“One should invent a bomb no larger than an orange that could blow up an entire city, churches, apartments and all.” — “I am in favor, “he continued, “of spreading certain types of bacteria among men and animals. spreading blight to destroy crops, anthrax to infect horses and livestock, and the plague to kill not only whole armies, but the inhabitants of whole regions. I call this all advanced military science.”

The world, above all the neutral nations, has a remarkably bad memory for such statements of a lovely soul. If one makes the excuse that at the time Churchill was a free-lance journalist, not an official representative of British policy, and that one cannot hold Prime Minister Churchill responsible for the statements of the journalist Churchill, let us consider a second statement, no less clear, from a British minister. It comes from a time when he was a minister, and represented the views of the British cabinet. On 9 November 1932, seven years before the beginning of the war, when the Weimar System was still at the helm in Germany, then Vice Prime Minister Baldwin said in a speech at the Guild Hall:

“The only defense is attack — or in other words, — if we want to save ourselves, we must kill women and children faster than the enemy.”

Which women and children were to be the objects of this attack was clear in a later remark by the same Mr. Baldwin:

Great Britain’s border is the Rhine.”

On the night of 12 January 1940, the first bombs of the war dropped by British airplanes fell in the open city of Westerland on Sylt. The first German bombs on British soil fell on 16 March 1940, on a flak battery defending British ships against German bombing attacks in the Orkney Islands. They were aimed not at civilians, but at a clearly military target. In following months, there were more British attacks on German cities and villages. No military targets were hit. The civilian population was always the target.

The 25 April 1940 report of the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht commented as follows on these fully ungrounded attacks on non-military targets:

“The previously mentioned attacks by British aircraft on the island of Sylt struck the spa at Wenningstedt, damaging several buildings. Enemy aircraft also dropped several bombs at the edge of the city of Heide in Schleswig-Holstein, though there are no military targets either in the heath or the surrounding area. The enemy has thus begun air warfare against undefended areas without any military significance.”

When the German military leadership provided documentary proof of the Allied plan to march into the Ruhr through Belgium and Holland and acted first, throwing back concentrated masses of troops in both countries, the English air force began to increase its air attacks against open German cities. The first treacherous attack came on 10 May 1940, when 57 civilians were killed in Freiburg in Breisgau, including 13 children ranging in age from five to twelve. After a major attack on the residential district of Düsseldorf on the night of 19-20 June 1940, the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht’s report announced:

“Since 10 May, enemy aircraft, mostly British, have been attacking open German cities.”

During the campaign in France, the British air force had more than enough opportunity to hit military targets. Here, where they really should have attacked — and where everyone in the world expected them to — they appeared only rarely. Where they here and there showed up to fight, they suffered catastrophic defeats. Even when its French ally in desperation asked for several squadrons to save it from threatening collapse, the British cynically turned them down. France, which covered the shameful British retreat from Dunkirk with the bodies of its soldiers, met its inevitable fate. Under the flows of the German military, it collapsed both militarily and in morale along the entire line. True to its old policy, England betrayed and deserted an ally that was no longer of any use to it.

England continued the war with fine-sounding speeches and with the same air terror it had begun against civilians on 12 January. The British aircraft, which were not used over the battlefields of France, Belgium, and Holland, instead appeared over German cities and towns. In his speech on 19 July, the Führer said:

“Mr. Churchill has once again declared that he wants war. Six weeks ago he began to fight in an area in which he apparently thought he was particularly strong, namely air warfare against the civilian population, with the claim that he was attacking so-called military targets. These targets since Freiburg have been open cities, markets and farming villages, hospitals, schools and kindergartens.”

Despite it all, the Führer extended the hand of peace once more. In the same speech, he said:

“At this hour, my conscience requires me once more to appeal to England’s reason. I believe I can do this because I come not as someone who has been defeated, but as a victor, and speak only for reason. I see no reason that compels the continuation of this war.”

But Churchill rejected this last change to unite with Europe. He responded to the Führer’s peace proposal with insults and air terror.

England’s historical guilt for the unleashing of air war against open cities is proven beyond any doubt.

What worsens the guilt of England’s leading circle is the fact that it knew how to conduct systematic hate propaganda aimed at Germany’s annihilation, and to promote air terror as a weapon of annihilation, making these the demands of the whole British people. There is abundant and unmistakable proof of this. Whether it is official statements by the British war cabinet or the editorials of greater or lesser journalists, whether in the sermons of leading clerics or letters to newspapers from every class — they all contain a fanatic hatred of the German people.

A letter to the News Chronicle from 1939 stated:

“To be completely open, I am in favor of exterminating every living creature in Germany, man, child, bird, and insect. I would not leave a blade of grass. Germany should look worse than the Sahara Desert.”

The famous English writer H. G. Wells wrote in the American magazine Liberty — as reported in the Daily Mail of 26 January 1940:

“I am convinced that heavy bombing, the destruction of cities and similar things would be a productive, healthy, and demoralizing experience for the Germans. Let the Germans take their own medicine.”

Even in 1940 they wanted the German people to take British patent medicine. As early as February 1940, before the first German bomb had fallen on English soil, the Star wrote:

“An appropriate dose of destroyed German cities and areas would probably do a lot of good.”

The Daily Mail reported on 29 April 1940 that it had already received hundreds of letters calling for “the random bombing of German cities.” This demand was growing daily in intensity and strength. It was coming from every part of the country and the people. The Daily Mail provided several typical examples.

Sir Henry Lawson from Catterick thought:

“We must level German cities.”

Miss Ida Turnball from Cambridge wrote

“Why do we not drop bombs on every street and shop in Germany? We have the best airplanes and pilots — why not turn them loose?”

A reader from Southampton wrote:

“Bomb any convenient German city for 48 hours straight. That would be a lesson for the damned Huns.”

Mrs. H. McRae Smith wrote:

“Why don’t we randomly bomb the Rhine? The Germans are very proud of their cities on the Rhine, and it would do them good to see their lovely buildings turned into ruins!”

Mr. H. Foster of Linton wrote:

“The destruction of German cities should be ordered.”

And finally, Mr. Morgan Porthcawl (Glamorgan) wrote:

“I hope that our flyers will pound German cities to bits! Only then will Germans see the light, and perhaps Hitler’s heart will be broken.”

The Daily Herald published a series of letters on this theme in April 1941. For example, Miss Dot Critshlay from Newtonfield wrote:

“Give the Germans something to choke on! Give the civilian Jerries a blow! Let them feel the strong power of the Royal Air Force, the best force in the world! For as long as they feel safe, their morale will stay strong. I will bet my best hat that the morale of our enemy will be a thing of the past, and the end of World War Number 2 will be significantly nearer.”

The British labor leader George Gibson said at a gathering in Leeds on 29 September 1941, according to an article in the next day’s Manchester Guardian:

“England can only win this war if it kills Germans. One can best kill them where there are a lot of them.”

When it comes to calls for the annihilation of the German people and covering bloody terror with the mantel of godliness, the clergy of Britain’s high church do not hold back as eager servants of British power politics. We have noted some of their “Christian” remarks. Reverend F. O. Baker, vicar of St. Stephens’s Church in London, said on 21 May 1941, as the News Chronicle reported on the next day, that twelve German cities should be flattened immediately. Reverend C. W. Whipp, vicar of St. Augustine’s in Leicester, had an even more “Christian” proposal, according to the “Daily Mirror” of 5 September 1940:

“The orders to the bombers of the British air force should be: Wipe the Germans out! No English flyer should return saying that he could find no military targets for his bombs. The order should be: Kill them all! We should use all of our scientific knowledge to invent new and more terrible explosives. I hope that the British air force becomes so strong that it can blow these German devils (the only word one can use to describe them) to pieces. But I will go even further. I will say it openly: If I could, I would wipe Germany off the map. The Germans are an evil race. Hitler is god of the underworld, and there will be no peace until everyone who believes in him is sent to hell.”

The perfidious British Pharisaism, which presents itself as “God’s chosen people” and which claims to be carrying out a divine mission as it implements its brutal policies, is shown in the following citation from the English magazine Cavalkade of 3 February 1940:

“We have learned from the Old Testament that God more than once ordered the extermination of an entire generation. We also learn that in one case those who did not obey God’s order to exterminate a certain people were themselves slaughtered. Are we not in a time of which the Bible speaks, when the cleansing of a people should occur?”

In the same pious style, the Manchester Guardian, in its 5 May 1940 issue, calls for a war against women and children in the name of Christianity:

“We must indeed” — so it writes — ‘regret the necessity of attacking civilians on Christian grounds, but we must grant that it is necessary to kill as many Germans as one can, whether they are wearing a uniform or not.’”

These statements come neither from overheated imagination nor a passing wave of hatred on the part of the British people, rather the British were and are in bloody earnest about annihilating the entire German people. That is easier said than done. But at least the British have not failed to try.

For three months, the Führer watched the criminal insanity of British air pirates. He gave the English people time to come to their senses and their catastrophic politicians time to see reason. But when finally the terror became ever more bold and their demands ever more impudent, the Führer gave the order to strike back. On 8 November 1940, the Führer said:

“You know that I have proposed to the world for years the cessation of bombing warfare, especially against civilian populations. Probably aware of what would come, England refused. Democracies are always clairvoyant. Well and good. Despite that, I have never waged war against civilians in this war. I allowed no night attacks on Polish cities. One cannot target precisely at night. I generally allowed attacks only during the day, and always against military targets. I did the same in Norway. I did the same in Holland, Belgium, and France. Then it suddenly occurred to Mr. Churchill to attack the German civilian population at night. You know how patient I am. I watched for eight days. They dropped bombs on the people of the Rhine. They dropped bombs on the people of Westphalia. I watched for another fourteen days. I thought that the man was crazy. He was waging a war that could only destroy England. I waited over three months, but then one day I gave the order. I will take up the battle.”

After England’s first satellites fell, the British attempted, with the help of their notorious Secret Service, to bring about an explosion in the Balkan powder keg. Using the shortsightedness of a small clique in Belgrade, they succeeded in involving Yugoslavia and Greece in the war. But these peoples waited in vain for military assistance, as had all of England’s other allies. They, too, rapidly collapsed under the blows of the German military. Thus England lost its last positions on the Continent.

During all these months, Great Britain was able to do nothing else in its waging of the war than to stubbornly continue its air terror against German cities and villages. But the British air force was unable to carry on its program of annihilation, since it was struck by the ceaseless revenge blows of the German air force.

22 June 1941 was the big event that Churchill and those behind the scenes in England and the USA had long predicted would change the war in their favor. The final source of military assistance, the military colossus of the Soviet Union, could be set in motion against Germany. The unleashing of the Bolshevist army would mean the end of a German army grown accustomed to victory. It did not bother Churchill in the least that he had only recently damned Bolshevism as the destroyer of all human values. As the lackey and tool of Jewish-plutocracy’s destructive goals, it was welcome. But England did not react to this turning point in the European military situation by taking active military measures, rather it renewed its bombing terror. Now that the German military was involved in a huge conflict to protect Europe from the danger threatening from the East and was already destroying the marching Soviet divisions, the British air force believed that its time had come. It thought that the German Luftwaffe was so involved in the East that it could no longer provide defense, or exercise revenge.

“Hitler is not strong enough to bomb England during the war in Russia,”

Radio London declared on 1 July 1941. The phrase “not strong enough” illuminates once more the fundamentally different military strategies of England and Germany.

Since 1939, the Führer has acted according to the laws of concentrated military leadership. That is, he was so strong on offensive fronts that he could win “model victories” in Schlieffen’s sense, and strong enough on defensive fronts so that he could stop the enemy. When he fought in Poland, he was on the defensive along the West Wall, but sufficiently strong to rule out an Allied offensive. When he fought in the West, he was strong enough in the East so as not to fear a successful attack there. During the Eastern campaign, the Western front is again defensive, but it is strong enough to resist any enemy attack, as the Dieppe adventure demonstrated. Due to its concentration of forces, Germany will win the decisive battle in the East, and thereby the war. England did not concentrate its forces. England wanted to be equally strong on every front, and therefore was not strong enough on any front to win a decisive victory. Thus they had big words to say about a Nonstop Offensive in June 1941, but could not do anything about it.

Between 22 June 1941 and 9 November 1941, the British air force lost 1570 aircraft without doing the German Reich any military damage. That also meant the loss of several thousand crew members.

The failure of the Nonstop Offensive has been admitted in England, since the losses can no longer be concealed. The Daily Post wrote in September 1941:

“The bombs of the British air force will never inflict as much damage on the German war industry as the German army is inflicting on the Soviet war industry.”

The New Statesman and Nation in London added this on 16 May 1942:

“The Germans can make critical military objectives almost impregnable. The Ruhr can still be attacked despite its strong ring of flack and spotlights, but precise bombing is no longer possible. It is, we fear, therefore wrong to assume that the bomber can make a decisive contribution to victory.”

The great loss of aircraft was particularly hard for the British. Major Oliver Stuart, the British air expert, announced rather quietly on 1 September 1941:

“The British air force currently has higher losses than before. The British are losing two to three times as many bombers as the enemy. The British loss of fighters is also higher than that of the Germans.”

This admission concealed the real loss balance during the months of the Nonstop Offensive, which was on average 10:1. The Daily Telegraph had to explain on 1 September 1941 that the British air force suffered huge losses in August 1941. 12 August was a particularly black day, as England lost 60 aircraft within 24 hours, while the German Luftwaffe lost not a single plane.

The British did not launch the Nonstop Offensive for military reasons. It was intended to be a massive attack on the morale of the German civilian population. Air Minister Sinclair spoke openly of Britain’s intent on 25 February 1941:

“We will see during the attacks of the next twelve months if bombs can shake the German people’s faith in Adolf Hitler.”

The British air minister has proven a bad prophet in this regard as well. German morale has not been shaken. The population of the threatened areas has endured and survived the attacks in an exemplary manner.

In its military and morale goals, the results of the Nonstop Offensive were the opposite of those of the accompanying war of words. All of England was captured by the optimistic illusions of its prime minister’s war of words. South African Premier Smuts declared that the Nonstop Offensive was already an invasion of Europe. The English did not need to land any troops. The British air force had begun the invasion, and would deliver the knockout blow. The previously cited air minister had big words in a speech on 19 August 1941 to British flight crews, claiming that the English air force would weaken the German will to resist and cause the collapse of German morale.

In America too, people eagerly latched on to the theory of “the second front in the air.” The New York Times, the New York Herald Tribune, and other papers argued eagerly that the inability of the German Luftwaffe to fight a two front war was the most critical current development of the war. Even more remarkable was a prediction in the Sunday Express of 7 July 1941, which claimed that Germany’s cities, forests and fields would be transformed into a sea of flames.

But all of these big words failed against the strength of German weapons and the attitude of the German people.

Churchill’s situation grew even tighter in spring 1942. England and the USA had had no doubts about the success of the major Soviet winter offensive, but the German military’s tough defense and its superhuman accomplishments ruined their hopes. The millions of German soldiers that the enemy happily claimed were freezing to death in the Russian winter suddenly displayed their full offensive power and seized the initiative. Their unexpected successes increasingly forced Churchill to do something about all the boastful statements and threats he had made over the course of the winter. The Kremlin pressed for the promised military assistance, and the Soviet demand for a “second front” could no longer be ignored.

Even the biggest optimists in England had realized, after nearly three years of war and an unbroken series of major German victories, that the German military could not be defeated with weapons. The hope that one could bring Germany to its knees by a hunger blockade vanished as German territory increased step by step to include the most fertile and productive areas of Europe. They vanished completely after the food reserves of the Ukraine were in German hands. One could no longer hope for a “sitting war,” the victorious end of which one could patiently wait for. The “irresistible Soviet war machine,” Churchill’s last trump after the failure of a half dozen other allies, did not flood into Germany, but rather was driven deep into the heart of Soviet territory in bloody battles with the German military, and was in itself in need of help. Churchill and his clique realized by the spring of this year — long before Dieppe — that a “second front” on the European mainland was impossible. After years of experience with their risky policies, we were nonetheless sure they would make an attempt. “Even the attempt is punishable,” Dr. Goebbels had written several weeks before the failed landing attempt at Dieppe. That they made the attempt despite its hopelessness speaks to the situation Great Britain found itself in. The rising number of ships sunk made the material and economic support of the USA an illusion. Rommel was winning in Africa, the Japanese in East Asia.

England had no other hope than that the air force could decide the war. As even England granted, the German armaments industry was distributed throughout Europe and was well defended. The only remaining target was the morale of the German population.

Thus in the spring of 1942, the British resumed their senseless terror attacks on the German population in the north and west of the Reich, at first with weak forces, then in mass attacks. Many of the Reich’s cities fell prey to British air terror.

During the night of 30-31 May, the British air force made its “big attack” on the residential districts of Cologne.

How the population of Cologne bore and overcame the largest British air attack so far is portrayed in what follows as an example of all the areas threatened from the air.

In the dark of night, the peaceful city of Cologne suddenly faced a terrible catastrophe, one that under some conditions could have led to a panic of unprecedented proportions. Preventing that was an urgent task as flames rose from every corner of the city, as whole buildings collapsed as the result of bombs of every caliber and blockbusters, as numerous people stared death in the face by being buried in rubble or asphyxiation in air raid shelters and basements, as the dead and wounded had to be dealt with, as babies, children, the sick, the aged and the weak had to be rescued from certain death, as people’s vitally important possessions and cultural and other treasures had to be saved from destruction. The instant action and calm behavior of Cologne’s women and children allowed Cologne to master the danger.

The behavior of Cologne’s population during the night of the British terror attack displayed true heroism, a heroism of loyalty and camaraderie, of courage, of determination, of a willingness to sacrifice for the good of the community. All Cologne became a single team to fight need and death, bombs and flames. In this most severe hour of testing, people grew in strength and bravery, in steadfastness and achievement. Each outdid the other in selfless labor and mutual support.

All of these characteristics, which the party developed in ten years of educational work, are the foundation of an unbreakable people’s community that, in the truest sense of the word, survived its trial by fire in the hour of common need. More than ever before, this night showed the true leadership of the NSDAP and its close relationship with the people. In unique camaraderie, leadership and people worked together in heroic struggle, and were victorious. All of those who stood together this night in the face of death and destruction — men, women, and children, political leaders and emergency forces, the police and fire departments, Hitler Youth and soldiers — displayed in every regard behavior that fills the whole German people with pride.

People in trouble! That always was and is the signal for the National Socialist German Workers’ Party to spring into action. It practiced the leadership role assigned to it by Führer and the people thousands of times during the many years of peaceful development. Its task has become even broader and more critical during the war, and particularly where the enemy threatens the lives of our people with death and destruction. British air attacks brought back for the men of the party a hard time of struggle — a struggle against the problems of the community — a slogan that has been the first commandment for each party member since its beginning. Once more, the property and lives of German people had to be protected in the face of immediate danger, at the risk of one’s own life.

From the start of the war, the NSDAP had been building a system to lead and aid in the event of an air attack, assisted by the party’s regular offices. As in a thousand other areas, this shows the ability of a carefully organized people. The political apparatus of the party is organized with the Führer at the top. Authority flows down through the Gau, the county, the local group, the cell, and the block, in ever smaller groups down to the smallest part of the people’s community, incorporating literally every individual in the great flow of strength that is the nation’s life. This proved itself in the time of the greatest common need in a splendid way.

The nerve center for the entire party’s activity in case of air attack is the emergency office. It is ready day or night. When the early warning alarm sounds, whether day or night, the local group offices are manned, and with the alarm sounds, all of the assigned forces in the cells and blocks are at their assigned posts. As danger nears, a thick network of observers and emergency centers is quickly in operation, which are in communication with the central office. If there is damage anywhere, it is reported to the emergency center as rapidly as possible. This office, in contact with the local air raid warden, sends the appropriate assistance. The orders are sent by telephone. If the telephone system fails, couriers, above all Hitler Youth members, are ready.

This network of men are entirely volunteers, men who have a long day behind them at a desk or factory, but who, when duty calls, are willing to sacrifice their nights for the good of the community. One has to realize how much discipline and self-sacrifice is required to leap out of bed every time an alert or warning sounds, often several times in a night, and hurry to the assigned post, not knowing if the warning will become an alarm and the alarm an attack.

All of the political leaders loyally display such unparalleled willingness to serve. They led the party and its organizations, from the leadership corps accustomed to giving orders down to the last man and the youngest woman. After the attack, Reich Minister Dr. Goebbels spoke to ten thousand Cologne citizens at a mass meeting at a large armaments factory. He spoke about the men of the party and its organizations, of the great test of those who were so often mocked as “Little Hitlers.” These “Little Hitlers,” Dr. Goebbels said, whom the Führer had to defend at the 1936 Nuremberg party rally against occasional complaints, have proven how seriously they take their task, risking their lives for the property and lives of the people’s community. Today, the title “Little Hitler” has become an honored title for many unnamed workers in the party.

Although the party had proved its mettle in numerous previous attacks, their first real hour of testing came as the British made their major attack. Wherever bombs fell or flames broke out, political leaders were there to care for the wounded, to rescue those buried in the rubble, to rescue household goods, to provide first aid for the homeless.

The work they did and the sacrifices they made during the bombing attack were so great, whether by man or woman, young or old, large or small, that a full account is impossible. We can only provided a few examples, taken in part from the press of Rhineland-Westphalia, or from conversations with the population of Cologne.

A large apartment building in the middle of Cologne was hit by explosive and incendiary bombs, and was in flames. Approximately 150 people were trapped in the basement shelter, which was blocked by rubble. The inhabitants would surely have suffocated if a brave man, a 50-year-old Sturmführer of the NSKK, had not recognized the situation and set to work rescuing them. An escape route had to be established in the adjoining building, also on fire, but with an undamaged basement. The wall had to be broken through. He had scarcely reached the basement with another bomb fell through into the basement and came to rest next to the wall that needed to be broken through. The Sturmführer, who through a miracle was unhurt by falling stones, did not know if the bomb was a dud or a treacherous time bomb that could exploded at any moment. Disregarding the danger, he calmly broke through the wall to make an exit for those who were trapped on the other side. First, many who had lost consciousness were rescued. Only then could one after another of the rest slip through the emergency exit. To avoid panic, the Sturmführer did not tell the inhabitants of the air raid shelter that there was a bomb next to their escape route. The time bomb exploded fifteen minutes after the last person had left the basement.

A long chain of women passed pails of water from one to another to a girl who sat for hours on a wall, throwing pail after pail at the flames to protect valuable food storage area. She refused to be relieved and did not rest until the fire was out and the food storage area safe.

A mason and a painter, whose own homes had been completely destroyed by a bomb, ignored British machine gun fire to reach the basement of a neighboring building where three women and four children were trapped under the rubble. Regardless of the risk to their own lives, they worked all night. Together, they also rescued an elderly couple who had fainted in a burning building and saved eleven people from other burning buildings.

A 70-year-old roofer hurried to a commercial building that had been set on fire by incendiary bombs near his home. A large fire threatened. “Here’s work for me!” he said, and climbed up the emergency ladder with a hose to the roof. He was surrounded by a ring of fire, and was in danger of being hit by further incendiary bombs. For two hours, he held the fire back, until he plunged through the burned roof to the next floor. His wife and others, who had been manning the water pump below, rescued him. He had five broken ribs and serious bruises. His courageous action saved the building and its contents. As the business manager wanted to thank him, he merely replied: “Not worth mentioning. That’s why I’m a roofer!”

Men and women spent hours bent over hand pumps in hard, monotonous rhythm. They kept a stream of water going to keep roofs from burning or to protect neighboring buildings from the greedy flames. Mothers rescued with their babies and children from basements took not only their own children, but those of their neighbors under their care. Two were carrying a baby under each arm, while the other women joined the rescue effort. One woman had given her child to a neighbor and was part of the water brigade. Suddenly, she saw that the fire had reached her child’s bedroom and flames were rising from the floor under the bed. The floor collapsed and the child’s bed fell onto the rubble. The women climbed through a window to the mountain of rubble, rescued the child’s bed, and returned to the street. A pail of water put out the smoldering fire, and that night the child slept in its own bed in the basement of a neighboring building.

Another woman, who had left her three children in a basement shelter, noticed that an incendiary bomb had fallen through the roof of her building. She went inside with her oldest child, a boy of eleven. Seven incendiary bombs had landed in the kitchen and bedrooms. The boy immediately emptied a pail of sand over the first bomb, another on the second, and yet another on the third. As he was covering the fourth bomb, it went off, burning both his legs. Despite the pain, he did not stop until he and his mother had extinguished the last bomb. Only then was he taken to the air raid shelter for first aid.

A 12-year-old girl was trapped in the basement of a collapsed building with her younger sister and grandmother. They were threatened with asphyxiation. Through superhuman exertion, the child dug through the rubble in total darkness until she could call for help. Through her bravery, the grandmother and both grandchildren were rescued.

The fate of a mother was frightening. Very pregnant, she found herself alone in the basement shelter with her little girl. The building had been hit by a bomb, and the basement was buried in rubble. Cut off from any assistance, mother and child were left to their fate. The neighbors and police who hurried to help took an hour and a half to clear away the rubble. During that time, the mother, in darkness and with only the help of her 11-year-old daughter, gave birth to her fourth child. Miraculously, mother, daughter, and newborn child were rescued.

A young worker, a Blockleiter in Cologne-Nippes, was asked for help by a young girl. On the way to the air raid shelter, a collapsing balcony knocked him unconscious. When he regained consciousness, he saw the girl laying next to him. He carried her into the air raid shelter of a neighboring building. Without taking the time to bandage his own wounds, he fought his way through the smoke, fumes, and smoke to the air raid shelter the girl had told him about, which was buried in rubble. Using a beam, he broke through the basement wall and rescued the trapped women and children.

Incendiary and explosive bombs caused a large fire in a warehouse on the Clevischer Ring. The warehouse was in flames, which had already spread to a shed nearby which held barrels filled with gasoline. The barrels were in danger of exploding, thereby endangering nearby undamaged buildings. A Blockleiter to whom the situation was reported fought through the smoke and flames, and succeeded in carrying one after the other of them out, though they were hot from the flames. Despite painful burns, he did stop until he had brought all of the barrels to safety.

A physically handicapped man succeeded in saving a large apartment building, on the roof of which a fire had broken out. He extinguished a series of incendiary bombs with water and sand. The only way he could prevent the fire from spreading to lower floors was to destroy the stairway that was his only escape. The next morning, the building’s residents found him suffering from light smoke inhalation and several burns.

A woman screamed for help from a burning building on the Old Market. A cell leader, a lathe operator by trade, attempted to fight his way into the house through the flames, but was knocked unconscious by a falling stone. A 15-year-old Hitler youth who accompanied him sprang through the flames to the injured man and brought him out of the burning building. As soon as the man was safe, he ran through the smoke and flames to find the woman, whose screams had stopped. While a new rain of incendiary bombs was falling all around, the boy found the woman, who had lost consciousness due to the smoke, and rescued her from certain death. As he finished his rescue work, the Hitler Youth collapsed, and had to spend a long time in the hospital due to smoke inhalation.

The Hitler Youth behaved splendidly during this night. “Children have become heroes here,” said Dr. Goebbels in Cologne. There are many examples of where children were the first to see a fire and began the work of putting it out. They tirelessly got sand and water to master the flames.

Pimpfs [members of the Nazi organization for young boys] and Hitler Youth had learned about dressing wounds and first aid during their outings and camp outs. This proved useful in many cases, as they were able to provide first aid for the wounded. The work these children and older boys performed is almost unbelievable. After hours of work, it sometimes took an order from a political leader before they were willing to stop.

During the night of the attack, the technical means the party used to communicate failed in large part. Hitler Youth took on dangerous courier duty. They rode their bicycles through burning streets, past exploding and collapsing buildings, which often blocked their way, forcing new and dangerous detours. But these lads carried out their assignments, bringing their messages to the most distant party offices, seeking whatever cover they could find from bombs and explosives along the way.

One of theses boys took shelter with his bicycle in the hallway of a building during a courier mission as a new hail of incendiary bombs began to fall. He noticed that incendiary bombs had fallen on the children’s home across the street. He ran across the street, broke a window, and entered the building. He was able to put out the fires with his jacket. The nurses and children in the basement learned only later the danger that they had been in.

Another boy and his bicycle were thrown against a wall by an exploding bomb. The boy was unconscious for several minutes. As he came to, he saw that his bicycle was destroyed. His legs were OK, but his head hurt and his arm and hand were injured. Losing no time, he continued on foot. The blast of a blockbuster threw him into the ruins of a shop, but he once again picked himself up and fought his way to the local group office, where he delivered his message. The second bomb had left his head and face bleeding heavily, but he did not want to stop or go to the hospital. He said: “A soldier would not even get a medal for such a wound, so why should I stop?” It turned out that his injuries were more serious than he thought, and he had to undergo a serious operation. His loyalty is a symbol for many deeds by unnamed comrades, and he was awarded the military service cross with swords.

Under heavy enemy attack, in the middle of a hail of bombs and shell fragments, police emergency forces hurried to major fires in the various city neighborhoods. Through the smoke, dust, and fumes, over rubble and broken glass, frequently endangered by bomb craters that could not be seen in the darkness, emergency vehicles went their way. They encountered damage from the beginning. At the first major fires, emergency teams of air wardens and small groups of police and Hitler Youth provided first aid. Together with the men of the party and the population, they worked tirelessly to save human lives and property.

In the Old City, a whole block had collapsed due to bombs and buried the inhabitants of an air raid shelter, cutting them off from contact with the outside world. Under the machine gun fire of enemy planes, at risk from falling flak and bomb splinters, threatened by the constant danger of collapsing buildings, they succeeded in making a small opening to at least allow fresh air to reach those trapped. After more work, the opening was enlarged and 51 people were rescued, many of whom had lost consciousness.

In some districts, large air raid shelters under burning buildings had to be evacuated because the buildings above were threatening to collapse. In most cases, the police succeeded in getting the people out of the smoking ruins and bringing them to other air raid shelters. In other cases, they had to rescue people from upper floors because stairways had collapsed. They used ladders and jumping sheets. Several police lost their lives, and many others suffered smoke inhalation and eye damage.

The fire department alone provided over one hundred fire engines for the air raid police. The anti-aircraft brigades near and far from Cologne hurried to the hard-pressed city. Even during the attack, convoys were rolling toward Cologne, fire brigade after fire brigade, one piece of equipment after the other. Far beyond the call of duty, the police also acted in a manly and selfless way, following the call of their heart and disregarding personal danger and loss.

In the middle of smoke and suffocating dust of collapsing buildings, a team of air raid police manned a fire engine. An explosive bomb fell in the immediate vicinity, causing severe casualties. There were several dead and many wounded. Still, the battle against fire and destruction continued, and priceless treasures were saved.

The medical service of the air raid police gave the injured first aid everywhere. In the middle or the street or in smoking rubble, the doctors and men of the medical service provided first aid and arranged the often not easy transportation to the nearest medical station.

Tower spotters passed on their news with long practiced precision to the central office, which thus had an up-to-date knowledge of conditions. Undeterred as explosive and incendiary bombs detonated around them and thick dusk and smoke stung their eyes, they kept at work. In once case, the observers remained at their post even though the roof all around them was in flames. Only an order from their superior made them leave their observation post at the last minute.

In past years, some did not have a clear idea of the importance of the Security and Aid Service (SHD). In the meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of people have personally experienced the valuable service these air raid wardens perform for the German people’s community, and how often they save the lives and property of Germans from destruction and damage.

The report of the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht on 1 June 1942 have honorable recognition to the exemplary conduct of all police forces:

“During the night attack on Cologne, the air raid forces — ignoring their own losses — prevented fires from spreading by their actions and courage.”

Protecting factories

During the attacks on residential areas, a few factories or plants were also hit. Here German workers proved the loyalty that binds them to their work place.

Many a worker risked his life to protect valuable facilities. There are “suicide patrols” at large and critical factories as well as among soldiers at the front.

A group of determined men at one factory, organized by the air raid warden, protected a large gas tank. Under a hail of explosive and incendiary bombs, these men were unable to seek cover, but had to remain in the vicinity of thousands of cubic meters of explosive gas to prevent a great catastrophe. Some assumed that such a tank, if hit by a bomb, would explode with sufficient force to level everything in its vicinity. The air raid warden, based on his experience in World War, was of a different opinion. But he was not sure. As an incendiary bomb broke through the full tank, the men sprang to the hole, filled it with loam, and pressed a steel plate against it with all their might to prevent gas from streaming out and air from entering. They were completely successful. There was no explosion. After the attack, they could make better repairs. But who knew that in advance?

The idea of neighborly assistance involves mundane matters in normal everyday life, but it showed itself splendidly in the hour of greatest need. Time and again, men and women left the work of extinguishing fires in their own buildings to rescue the lives of others. Not just those affected by bombs and fire were in action. All of Cologne was in the streets. The streets were mobilized, but not in the way London expected! It was the mobilization of fraternal assistance. “The roof is on fire,” someone would shout, and immediately the building’s inhabitants and their neighbors were at work. As soon as someone shouted “Water!,” a bucket brigade already stretched from the hydrant to the building. The phosphorus stuck stubbornly to the roofs, but even more stubborn was the will of people to resist, attacking repeatedly with water and axes to save what could be saved.

This showed the results of the years of education the Air Raid Society had conducted for the German people. Even during the years of peace, it tirelessly acquainted the broad public with practical information on combating bomb damage. Without that training, important treasures not to be underestimated would have been destroyed during this war.

Here, where the homeland became the front, camaraderie between the armed forces and citizens was displayed in a wonderful way. The citizens of Cologne remember thankfully the work of the pioneer brigades, whose trained forces immediately set to work digging out those buried in rubble blasting rubble, and cleaning up. Those whose homes were damaged or who were homeless were particularly thankful for the army’s field kitchens, which were set up at the Gürzenich, the opera house, and many other locations, serving hearty portions.

The first efforts during the night of course went to caring for injured people and providing first aid, but everything possible was also done to protect people’s material goods from damage or destruction. Much furniture was saved. There were piles of clothing, towels, beds, tables, chairs, cabinets, suitcases, sofas and other household goods in the street. Here too people helped each other as much as possible. First one building was emptied, then the next.

Thus an attorney helped a locksmith to rescue his possessions from a neighboring building, then both set to work to rescue his own possessions. The attorney wanted to rescue a treasured possession, his baby grand piano. Together with the locksmith, he got it to the street undamaged. The attorney’s daughter lifted the lid and played a little children’s melody. For a moment, it sounded like a fairy tale in the midst of the smoke and fume-filled night. People listed for a moment, deeply moved — then got back to work. When the worst was over and people could catch their breaths once more, the owner of a little shop sat down at the piano. Hitting the keys harder than usual, he played a song familiar to everyone in Cologne, one they had often sung together at more peaceful times: “They will not beat us, they will not beat us, they will not beat us to the ground!” That is real courage!

Thousands of other examples could be given of passionate will to life, of devoted duty, of selfless assistance. All of Cologne this night followed the law of unbreakable perseverance, which all readily affirmed. Everyone joined the fight against terror — women, too, who can no longer be spoken of as the “weaker sex.” It is true that many women are frightened by a mouse in a room, but when it comes to defending life and health, their family’s possessions and those of the people, they display no less toughness, endurance and bravery than a man. Everyone, man, woman, and child, made superhuman efforts.

Over 40 percent of the fatalities did not die in their homes or air raid shelters, but rather in active rescue work. Just as a soldier at the front stays at his post regardless of every danger, so the men and women of the homeland did their duty, often without knowing if something had happened to their closest kin or to their home. They fought terror and need to the last — and they won.

This truly military behavior of the city’s 800,000 inhabitants filled some old front soldiers with amazement and pride. And old World War officer, now a political leader, experienced the terror attack and recorded his impressions: “In 1917, my company and I experienced a terrible air attack. We were marching to relieve a battalion at Chemin-des Dames, and spent the night in a destroyed village behind the front. Tommy came during the night and dropped bombs on us. He seemed to know we were there, and bombed us for an hour. The bombs destroyed whatever was left in the village. I was a corporal then. As I took the important papers from my burning quarters and tried to find someplace safe for them, I saw that all around me buildings had been hit and were on fire, and watched the young soldiers of my company seeking cover in ditches and behind ruins. This feeling of helplessness against an enemy one cannot reach is the worst thing I experienced as a soldier. I wondered if the young lads could hold out. Are they still a unit, or only a group of scattered men thinking only of themselves? Then came a moment of silence, and the captain’s command came through — and the company came together. Discipline prevailed. Everything was in order, and each did what he was ordered to do. It was exactly the same later during the great battles.

I thought back on that night in later years, and see it as an example of military discipline that young recruits had learned through hard training. I had never thought it possible for a whole city, women, children and the aged, to display such conduct under conditions of life and death. But I saw and experienced it in the night of the attack on Cologne.”

As morning dawned over the burning and smoking ruins, it became clear what Cologne has lost in the night. It was a great deal — valuable human lives, precious possessions, the familiar streets, churches and monuments of a thousand years of history, whose stones had formed the face of the city. But one thing the citizens of Cologne had not lost: themselves.

The day after the attack, British observation planes flew high over the city to photograph the damage. What these cameras — which the citizens of Cologne called “Churchill’s big eyes” — bought home would have shamed any German pilot. The photographs certainly show destruction, but not the destruction of military targets, but rather of apartment buildings and hospitals, schools and culturally important buildings, and a number of churches that were among the greatest treasures of German architecture. They included “Marie im Kapitol,” built in the eleventh century on a Roman foundation, which was a model of organic artistic development from the earliest stages to the late Gothic. The treasure of late Roman church architecture on the Rhine, St. Aposteln, and the equally unique Church of St. Gereon, whose ten-cornered central cupola and high chancel were built over a thousand years, were heavily damaged.

What British flyers brought home was shameful evidence of destroyed works of art known and loved all over the world by experts as well as ordinary people.

These buildings were more than that for Cologne. They gave city neighborhoods their names and character. A citizen of Cologne is proud to live by “St. Gereon,” or “the Kapitol,” or “the Lichthof,” or on “the Salzgasse, or the “Old Market.” Almost more than his own losses, he was affected by the destruction of what generations had been bound to, from childhood on. The churches and other destroyed monuments were not mere showplaces to Cologne’s citizens, the kinds of places American and English traveling snobs, armed with their Baedeker guides, visited before the war, making loud but empty comments about. They are part of Cologne’s landscape, the foundation of its thousand years of proud history. Memories and duties speak to him from every stone, forming his thoughts and feelings, his attitude toward life, the way he lives. This wealth gives Cologne’s citizens the foundation for their true behavior, which does not boast of what they have. This deeply rooted consciousness of history never leaves them, whatever the need or danger. That is the peculiar nature of the citizens of Cologne, and it is something that British cameras could not photograph, nor can it be destroyed by bombs or terror.

Cologne’s heart held firm through the destruction. During the night, they never lost self-discipline. Not once was the population overwhelmed by pain and terror, nor did they panic or lose their heads, as can so easily happen to masses under conditions of terror. There was no gloomy desperation that morning in Cologne. As day came, the city’s will to life was unbroken.

In the days following the attack, Cologne’s party offices and agencies displayed activity and responsibility that shows a refreshing ability to do new things. It is proof of the youthful vigor and flexibility that National Socialism has brought to the leadership of the German people. Gauleiter Grohé who led the recovery efforts as he had the night of terror, inspired the hearts of the citizens of Cologne with proud words. The Gauleiter said:

“Citizens of Cologne! In the midst of the work we all have to do since Saturday night, I have a few words to day to you.

Aside from the heavy damage done to our beautiful city of Cologne by order of the criminal Churchill, there is hardly a one of us who has not also suffered personally from this night. That makes the behavior of the whole population the night of the attack, and in the days following, even more admirable. It will take much patience and a long time to overcome the damage of that night’s attack, but you all have seen how from the first moment on, everything possible was done to provide help wherever it was needed.

With deep respect, we remember those who lost their lives. In light of their sacrifice, we can bear the material damage, knowing that it can be repaired.

Food and other supplies are assured. Sufficient housing was reserved for those who became homeless, and each family that lost its home will find decent housing elsewhere in our region. The transportation equipment is ready. The party’s local groups are expecting their arrival. Obviously, those with critical occupations will remain in Cologne and will accept the housing offered to them. Should criminal elements take advantage of the current situation, immediate judgment is waiting.

Citizens of Cologne! Your actions and attitudes have given many soldiers who were home on leave or who are stationed here compelling proof of your courage and willingness to sacrifice, showing the same spirit as that of the front.

The Führer was the first to hear of the situation in Cologne, and followed it through the night. He expressed to me his deepest appreciation for the conduct of the entire population of Cologne.

I know that you will prove worthy of this appreciation in the future as well!”

Grohé

Gauleiter and Reich Defense Commissioner for Military District V

It is hard to imagine, and even harder to describe, the enormous scale of official measures that are necessary to get a city like Cologne over the first shock of such an attack. The life of a great city is tied to the functioning of numerous offices, each depending on the other. The enemy’s bombs brutally disrupted this finely tuned organism, putting numerous parts of it entirely out of action. The first task was to restore essential services, repairing the torn connections and reestablishing the flow of life.

The city administration played a major role in these tasks. Just as with the party, every city office has emergency plans that are implemented when needed. The city was, of course, prepared in theory for an attack. But it is equally obvious that there is no “manual” for dealing with such situations. The terror attack on the last night in May presented the city administration with new and unforeseen situations that could be mastered only through the personal action of men with strong wills who were used to giving orders.

At the beginning of the attack, as always, first aid workers were at their posts in every local group. They provided an approximation of the number of injured shortly after the end of the attack. These women were the bridge between the work of the party and that of the city. They referred the displaced to emergency shelters — usually schools — and provided clothing if necessary. The emergency shelters were not needed to a great extent. Most of the homeless found immediate shelter with friends or relatives. Without saying much, all those who still had their homes made space for their neighbors who needed it. Cologne was one big family.

The first aid workers provided everything necessary for community life to those who were displaced, including credit slips, ration cards, certificates for clothing, etc. They avoided bureaucracy. The displaced were served during the first few days without ration cards. Everything was thought of. Women who the next morning stood helplessly outside food stores without their customer cards were served. A stamp from the relevant local group gave them the right to be served like any regular customer.