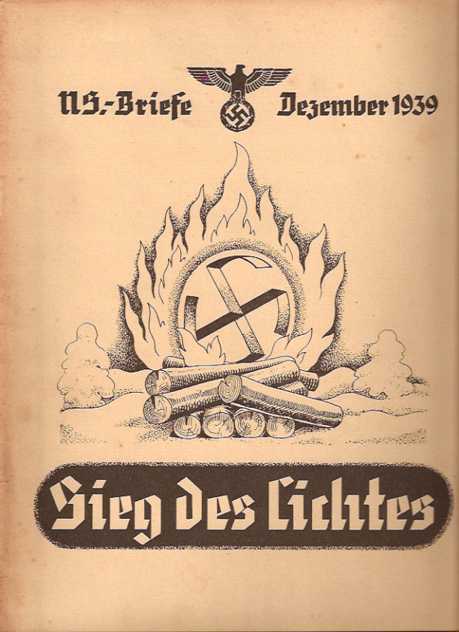

Background: The Nazis put significant efforts into de-Christianizing Christmas, focusing instead on the winter solstice. This 1939 article from a Nazi educational monthly for the Frankfurt area. The war had been in progress for four months.The entire issue was devoted to Christmas. Other material on Nazi Christmas celebrations is available on this page.

The source: Wilhelm Beilstein, “Wie wir Weihnachten feiern,” N.S.-Briefe, December 1939, pp. 327-328. The section is reprinted from Beilstein’s Lichtfeier. Sinn. Geschichte, Brauch und Feier der deutschen Weihnacht (Munich: Deutscher Volksverlag, 1939).

How We Celebrate Christmas

by William BeilsteinChristmas is to us Germans the most lovely and meaningful season of the year. From it, we gather inner strength and power from the eternal life force of our nature. Mother and child, family and kin are at its center. It is not limited to a day that swiftly passes, but rather it encompasses a long period of preparation and many mythic beings and customs. Despite many foreign influences, over the course of centuries it has remained an ancient German holiday, and its nature can only be understood within the territory of our people. Today, we have once again come to know the true meaning of our Christmas customs and traditions, freeing them from foreign names and influences (see the article in N.S.-Briefe of December 1938). The following remarks will provide ideas and direction for organizing Christmas and Advent festivities.

The Winter Solstice

The real Christmas community celebration (which we cannot conduct this year due to the demands of the war) is the winter solstice. For many years, it has been a part of our Christmas celebrations that can no longer be done without. It should in no way replace the Christmas celebration within the family. This ancient custom of our ancestors should instead deepen and enrich it. The winter solstice celebration is not a matter for party organizations, but rather a matter for the whole people. Party units only organize the ceremonies. The whole people's community should participate in celebrating the winter solstice. However, the events will differ from place to place. In smaller places, the whole village community can gather around one fire. In larger cities, it has to be done by local groups, or even by individual party organizations. The community experience, in such cases, is maintained by lighting the fires at the same time, and by returning to a central gathering place for a community meeting. The torches of those coming together can then be thrown into a community fire. The community fire will be kept burning by party organizations until 24 December. On 24 December, families can light a candle from this fire and use it to light their Christmas tree candles at home. Many have participated in this ceremony in recent years in Augsburg, Zittau, and Koblenz. This custom seems well-suited to become the general practice, since it signifies the being and growth of our people's community from the spark of the worldview that the Führer lit in our hearts.

The real Christmas community celebration (which we cannot conduct this year due to the demands of the war) is the winter solstice. For many years, it has been a part of our Christmas celebrations that can no longer be done without. It should in no way replace the Christmas celebration within the family. This ancient custom of our ancestors should instead deepen and enrich it. The winter solstice celebration is not a matter for party organizations, but rather a matter for the whole people. Party units only organize the ceremonies. The whole people's community should participate in celebrating the winter solstice. However, the events will differ from place to place. In smaller places, the whole village community can gather around one fire. In larger cities, it has to be done by local groups, or even by individual party organizations. The community experience, in such cases, is maintained by lighting the fires at the same time, and by returning to a central gathering place for a community meeting. The torches of those coming together can then be thrown into a community fire. The community fire will be kept burning by party organizations until 24 December. On 24 December, families can light a candle from this fire and use it to light their Christmas tree candles at home. Many have participated in this ceremony in recent years in Augsburg, Zittau, and Koblenz. This custom seems well-suited to become the general practice, since it signifies the being and growth of our people's community from the spark of the worldview that the Führer lit in our hearts.

The winter solstice fire each year brings many millions of Germans into the winter forest and forges them strongly together into an unshakable unity. And the solstice fire has always been a proclaimer of Germandom along our borders. In the past, the solstice fire was never a sacrificial fire to some sort of divine being. It was always a reminder, an symbol, an affirmation by our people of the eternal laws of life. It burned in times of trial, and in times of joy. It was lit in 1813 during the wars of liberation, and by the youth movement before the war as it turned away from the stable in Bethlehem and the songs of hosanna to the Son of David. Friedrich Ludwig Jahn rightly described it in these words:

“As long as our people remains true to the customs of its fathers, as long as the flames burn from the mountain tops at mid-summer solstice and from the German countryside at mid-winter, so long will glow the spark of enthusiasm that will burst into flame when the people most needs it, the flame in which the traitors, troublemakers, and liars who threaten our people will meet their well-deserved end.”

The custom has developed of remembering the dead of the war and of the movement by throwing wreaths into the solstice fire. For several years, the SS has organized a strong, manly dance with torches that ends with the lighting of the fire. The impact of the solstice fire comes more through actions and symbols than through words. The last part of the march to the site of the fire is silent. The speech at the site of the fire must be brief and compelling. It must be an appeal to action, not simply a statement that our ancestors celebrated this way a long time ago. The experience of the towering flames, the winter stars, and the snow-covered German landscape means more to us than words.

Christmas in the German family

For us Germans, the high point of Christmas eve is the burning candles on the tree, within the circle of family and kin. Four weeks earlier, the Christmas wreath with its four red candles was hug. On Ruprecht’s Day, 6 December, Ruprecht, Father Christmas, came to the children. From then on, there is noise and song during the long days as people make little presents. The little children watch all that happens during these days. Mother hardly knows how to answer all their questions. Repeatedly, she tells about the Father Christmas and his helpers, the elves and dwarves, of Frau Holle [from Grimm’s Fairy Tales], Snow White, Little Red Riding Hood, of Hansel and Gretel and all the others, for Christmas is a time for our children to hear fairy tales. When the day comes, the shining eyes of her children are a mother’s best thanks for all the work and love she has put into preparing for the holiday. What is Christmas without children, what is life without the sacrifice one generation makes for another.

Mother and child are at the center of Christmas, giving it meaning and holiness. Can we think of anything greater than honoring motherhood? Our ancestors called the holiday “Holy Mother’s Night,” and thereby gave expression to our deepest feelings. Each year, millions of German mothers experience the miracle of birth. At Christmas, we honor love, motherhood, and family, and on the day in which the sun is reborn we believe in the victory of truth, goodness, and beauty. For us, Christmas is truly the festival of love, the festival of the community of our people, and the festival of light of the German soul.

Each family celebrates Christmas in its own way. We do not want to prescribe how it should be done. Those for whom it is possible take their children out into the winter landscape once again on Christmas afternoon to show them how seeds are sprouting under the snow, and how the Christmas roses are blooming. Then they return to their warm home with happy, gleaming eyes and rosy cheeks, waiting for the bell to ring behind the closed door of the room with the Christmas tree that signals them that they may enter, and the whole family gathers by the light of the tree. The little hands of the smallest child reach for the flickering candles and the sweets. New surprises are discovered on the tree, and it is hard to get the attention focused on the quiet ceremony that is introduced by a song. One may not neglect the song “Oh Tannenbaum,” nor the new Christmas song “Night of Clear Stars.” The children please the parents by reciting a little poem, and then sit on their parents’ laps to hear the story of the "shepherd boy who became king," or the story of "the baby in the cradle, deep in the mountains." Old and new tunes sound forth, and touch the most tender aspects of our German nature.

If the participants are primarily adults, one of them can perhaps speak briefly of coming and going in nature, of the coming and going of light and of people, of battle and work, of the sanding together of family and people's community, of building strength from the stillness of home and nature. He can tell of the fathers and brothers, or read a letter from someone at the front, where he protects the homeland. He should remember those who sacrificed themselves for the people, and should recall the mothers who preserve the people’s life. In these moments, everyone will be proud of our people's great deeds, and will thank Providence for giving us a Führer when we most needed him, the one who taught us to see the laws governing our lives, who gave us back our honor and freedom.

Then presents are exchanged. That is not the most important part of the holiday, but one must carefully consider the gifts one gives. Gift giving must never become simply an exchange of merchandise, but rather give things that are appropriate for the person, and will bring pleasure. Keep the presents secret, for that belongs to the holiday as much as the candles on the tree and mother’s baking.

The grownups will sit together for a long time and tell their stories. Most of the time, a member of the family will be away with the labor service, serving in the military, or working at a distance from home. Everyone who can goes home for Christmas Night, even if it takes a day’s travel, to celebrate within the family circle. If that is not possible, we try to do something for the one far away. In our literature, we have lovely stories of Christmas celebrations of Germans in foreign lands or on foreign seas, of the homesickness and sacrifices they endure, those who are doing vitally important work on Christmas Night and therefore cannot join their families.

When we celebrate a German Christmas, we include in the circle of the family all those who are of German blood and who affirm their German ethnicity, all those who came before us and who will come after us, all those whom fate did not allow to live within the borders of our Reich, or who are doing their duty in foreign lands amidst foreign peoples. Wherever Germans may life, whether in the Brazilian jungle, under Africa's sun, in the heights of the Carpathians, or in the confusion of New York, they turn their thoughts to the homeland in the Christmas season. Their eyes follow the clouds moving toward German's soil. Their longing for their home grows, and their memories of childhood come back as they recall their mother’s German words. The ties between Germans on both sides of the border grow stronger which, on Christmas Eve Reich Minister Rudolf Heß speaks over the radio to the most distant people’s comrades, saying that we will never forget them, that they belong to the great family of the German people, which has risen again and has a great future.

Last edited 4 November 2025Page copyright © 2007 by Randall Bytwerk. No unauthorized reproduction. My email address is available on the FAQ page.

Go to the 1933-1945 Page.

Go to the German Propaganda Home Page.