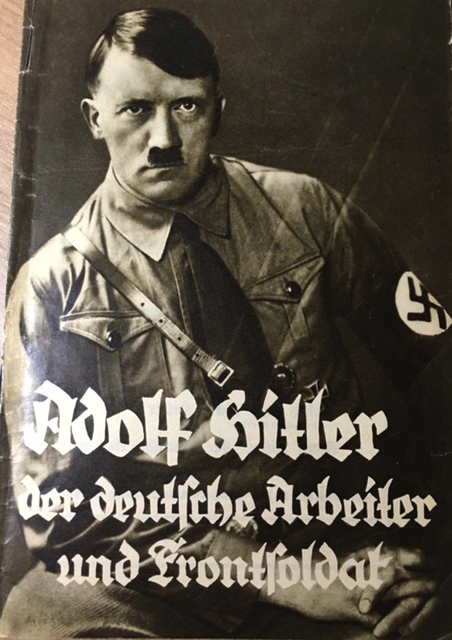

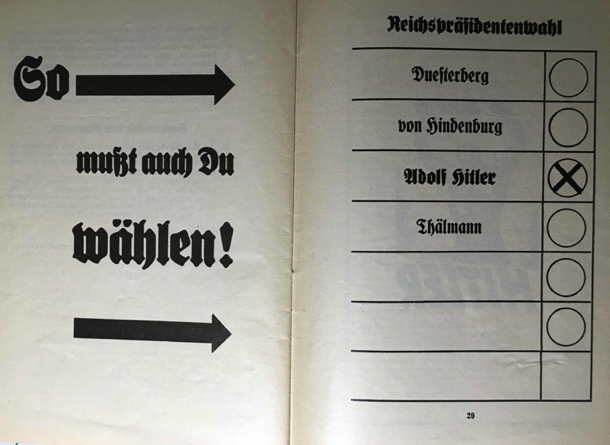

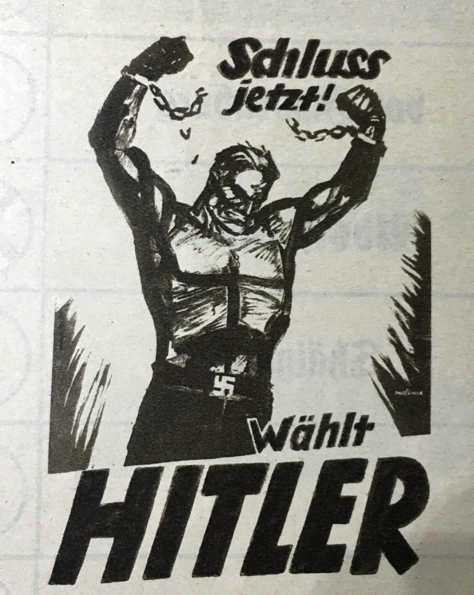

Background: This is a mass pamphlet issued by the Nazis during

the first round of the 1932 presidential campaign, held on 13 March. It presents Hitler as a model in every regard. I do not know how many copies were printed, but surely it was in the hundreds of thousands, even millions.

Background: This is a mass pamphlet issued by the Nazis during

the first round of the 1932 presidential campaign, held on 13 March. It presents Hitler as a model in every regard. I do not know how many copies were printed, but surely it was in the hundreds of thousands, even millions.

The source: Dagobert Dürr, Adolf Hitler der deutsche Arbeiter und Frontsoldat (Munich: Franz Eher, 1932).

An unnecessary question: Adolf Hitler, of course!

But who is Hitler?

You think that every child knows about Hitler? You are both right and wrong. Everyone knows that Hitler is the brilliant Führer of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party that had seven members thirteen years ago and today is the most powerful people’s movement in Germany, or anywhere in the world.

But very few know how Adolf Hitler gradually achieved the decisive importance for the fate of our fatherland that he has today. Very few know his whole powerful personality as Führer and human being.

One person thinks he is a foreigner, probably a Czech, another thinks him the representative of big capital. Some say he is a base demagogue with no statesmanly abilities, while other “big brains” think he is a cultural barbarian or a soulless brute.

In these pages you will learn who Hitler really is.

“Hitler is a foreigner, a Czech!”

Why?

He was born in Braunau in Lower Austria. Braunau on the Inn — not to be confused with Braunau in German Bohemia —is a small, purely German town on the Bavarian border, part of the “Inn district” that was cut off from Bavaria and given to Austria in 1779. Three generations before Adolf Hitler’s birth it was still Bavarian, and it is only the result of dynastic disputes that it is today part of Austria.

Even so, are not the Austrians our blood brothers whose return to the Reich is longed for with the same intensity on each side of the accursed border markers? Adolf Hitler himself writes of this in the first chapter of his book Mein Kampf:

“Today it seems to me providential that Fate should have chosen Braunau on the Inn as my birthplace. For this little town lies on the boundary between two German states which we of the younger generation at least have made it our life work to reunite by every means at our disposal.”

Adolf Hitler was born on 20 April 1889 in the customs house at Braunau, the son of an Austrian customs official, only a few minutes from the border. Hitler’s grandfather was a poor cottager from the Forest Quarter.

No one can claim that Hitler’s ancestry sowed the seeds for his later development. As a simple son of the people, he has risen only because of the strength of his brilliant personality and soon will hold the highest office in the Reich.

He has one of the essential experiences necessary to lead the state: a deep understanding for the needs of the people, for its feeling and thinking, an understanding that is so often missing from those with more elevated births. It will be impossible for someone like Hitler to plunge the people into the bitterest misery with ever new emergency decrees, for he himself knows what hunger means.

He suffered hard blows of fate in his youth. Contrary to his own desires that inclined him to the visual arts, his father had him attend secondary school. When Adolf Hitler was thirteen his father died of a heart attack. After a severe illness, his mother allowed the boy to give up his father’s desire that he become a civil servant and to follow his own desire to study at the art academy. The boy left secondary school, where he had for the first time came to a German national consciousness under official pressure, and to the knowledge that he expressed in the following words:

“That Germanism could be safeguarded only by the destruction of Austria, and, furthermore, that national sentiment is in no sense identical with dynastic patriotism; that above all the House of Hapsburg was destined to be the misfortune of the German nation.”

The happy dreams that were leading him to the fulfillment of his dearest wish, however, met an abrupt end when his mother died two years later after a long and painful illness.

A time of bitter poverty now began for the lad. His studies were over. His orphan’s pension was not enough to live on. Thus Adolf Hitler went to Vienna, forced even as a child to earn his own way.

“To me Vienna, the city which, to so many, is the epitome of innocent pleasure, a festive playground for merrymakers, represents, I am sorry to say, merely the living memory of the saddest period of my life.”

That is what Adolf Hitler wrote about his time in Vienna. Czech-Jochberg’s book Hitler describes in detail how the poor lad, after failed attempts to attend the art academy and architectural school, became a construction worker who did not want to be organized by the Marxists.

One can only be as lonely as Hitler was in a big city. His 50 Guilder, a small fortune in Linz, melted way like frost in the March sun. It was just enough to enjoy an evening glass of new wine in Vienna.

“I will take any job I can find,” Hitler decided.

Preferably in construction so he could remain in the field.

The employers and foremen, however, shrugged their shoulders: “We only need trained workers.”

“I can work...”

“Do you have a certificate?”

He did not.

As he was going: “If you are willing to be a common laborer...” He did not want to, not at all, but he had to.

On the street below one heard the clopping of horses as a calvary officer drove his cart past. Women with whole flower gardens on their hats tripped past, as fast as their long skirts allowed.

Every face radiated good cheer. Vienna, the city of songs. —

One heard no songs where Hitler lived. An old lady complained in the courtyard, adding to the racket. The odor of mice drifted through the window, its broken pane covered with a sheet of paper. A fellow roomer from the construction site tossed him a newspaper. “Read that... a girl was kidnapped at the Prater and taken to a meadow where they did who knows what, then they threw her body into the Danube.” The newest crime, a sex murder. intellectual nourishment for the people!

Hitler stormed out. Perhaps he would be able to get standing room at the opera.

A scream came from the kitchen window. . . like a siren.

Worker Kaudelka was beating his wife. Yesterday was payday. Who was not drunk?

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

Did no one notice these people, who slept on Friday with their heads on the table at a suburban building because they did not want to go home, who skipped work on Saturday and begged a neighbor on Monday for a few coins to buy bread?

No, the supervision was not that bad: The same agent who debated the people and religion and progress with Hitler during the lunch break went to the foreman, pulled on his cap, and said: “We won’t work with this guy... He is no good.”

The foreman looked at the angry man, thought a bit, decided that it was not necessary to get into a fight about a common laborer, and fired Hitler.

How often he had that experience! He wandered from construction site to construction site, became more silent and bitter. When he was not at work, there were times when he could talk. But one speaks poorly when one is hungry.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

Something else happened. Some workers put their heads together, gave an evil glance toward the laborer, and said: “Throw him off the scaffolding ....!”

Reason objected: “Aren’t you ashamed of yourself...!”

“It would be an accident ... we’d done with him.”

“What has he done to you....?”

The ringleader pulled together the words that he had heard from his union boss: “He is hurting our movement, a traitor....”

The other gave a rough laugh. There would be some fun today. But an older worker took Hitler aside and told him to leave before he plunged off the scaffolding and the watchman took his pencil to write “Accident at a construction site...”

As miserable as these five years of bitter poverty and hunger were, they also provided the gradually maturing lad with the knowledge that would be fundamental to his future development.

As a boy he had learned to distinguish true nationalism from dynastic patriotism. Now he learned how fundamental different true socialism was from Marxism and bourgeois charity.

He had suffered the poverty of the workers enough as to never be able to forget it. The foundations of later National Socialism were laid during those hard days in Vienna.

At the same time, his visits to the Austrian parliament brought him to a permanent disgust with empty parliamentarianism.

This period in his life makes us certain that Adolf Hitler, a man of the people who stood as a worker on the scaffolding, is better able to serve the people as Reich President than some high-born excellency, and that he will put an end to the limitless parliamentary chatter that has brought us so much misfortune.

“Hitler is a deserter.” That is the latest and perhaps crudest lie printed by Vorwärts of all places, the paper of the notorious party of deserters.

Hitler, they say, left Austria without serving, and thus was a deserter. He volunteered for the Bavarian army when the war began only to avoid being sent back to Austria as a deserter.

In fact, Hitler left Austria when he was 23, long after he had registered for military service. He was classified as temporarily unfit for service.” The official documents were recently provided to the “Brown House” [Nazi Party headquarters in Munich] by the relevant Austrian agencies. No calumny is too crude for the Jewish press to use against the true leader of our people.

Adolf Hitler came to Munich in the spring of 1912, where he earned his bare living as a painter until the war broke out. He then volunteered with the Bavarian army, to which he was accepted with the permission of the king. Given his opposition to the Hapsburg state and his enthusiasm for the German Reich, this was an obvious step.

He did his duty at the front for four-and-a-half years. He was wounded several times and received the Iron Cross, First Class for his exceptional ability as a simple corporal.

Adolf Hitler's war comrade Hans Wend, the “white horse” of the List Regiment (16th Bavarian Infantry Regiment) writes in his book Adolf Hitler in the Field about Hitler’s exemplary attitude at the front. Here is one passage:

“I have no relation to Adolf Hitler and have absolutely no desire to present him as a hero. However, it is a hateful tactic of his political opponents to claim in their press that he was a corporal at the regimental staff who never showed the ability to become a squad leader. I wish to note about this article, which I read in a Social Democratic newspaper, that the author of these lines about Adolf Hitler’s activity in the field was badly informed. Some squad leaders would not have felt up to the demands that Adolf Hitler faced as a battlefield courier. I have often had the opportunity to meet with former regimental comrades who also were in the List Regiment with Adolf Hitler. Although their political opinions were very different that those of Hitler’s movement, they were appalled by the crude ways used to denigrate Adolf Hitler as a front soldier. Each who knew him in the field must admit that he was the model of a front soldier. It is unfortunate that there are still Germans who prefer to see the front soldier as a criminal rather than as a hero.

A few days after the battle of 20 July I met a solder in Saintes who told me that Hitler had behaved with exceptional courage and bravery during the bombardment that lasted for days and which destroyed all telephone communications. He had done a great deal for the regiment. Battlefield courier L. told me that when the English command sent forces from an Australian division to attack our position on July 19, Adolf Hitler calmly observed their movements and provided our command with important information.

It was the regiment’s decision that he did not become a squad leader. The regimental staff did not want to lose Adolf Hitler’s services as a brave and dependable battlefield courier.”

Adolf Hitler was seriously wounded by a gas attack at Ypres on 14 October 1918 and was blinded. He was sent to the Pasewalk hospital in Pomerania There he lived through the November Revolt.

As a result of this disastrous collapse, Adolf Hitler vowed to dedicate himself to the rebirth of the fatherland.

His iron will speeded his recovery. By the end of November 1918 he returned to Munich where he joined the so-called councils (Räteherrschaft). His determination and energy led to his arrest.

Then he became a so-called “educational officer” for a Munich regiment. One day he was sent to investigate a political movement called the “German Workers’ Party,” which was holding small meetings. Hitler became the seventh member, and with his brilliant political ability and his iron drive he created the National Socialist German Workers’s Party, today a movement of millions.

That is how Adolf Hitler became a politician, and soon he had unique success.

It was quickly clear that he had unusual rhetorical ability. Speeches alone are not enough to build an organization. He also proved able to solve organizational questions brilliantly, and to understand political problems and situations. He carried out what he saw to be necessary with bravery and determination.

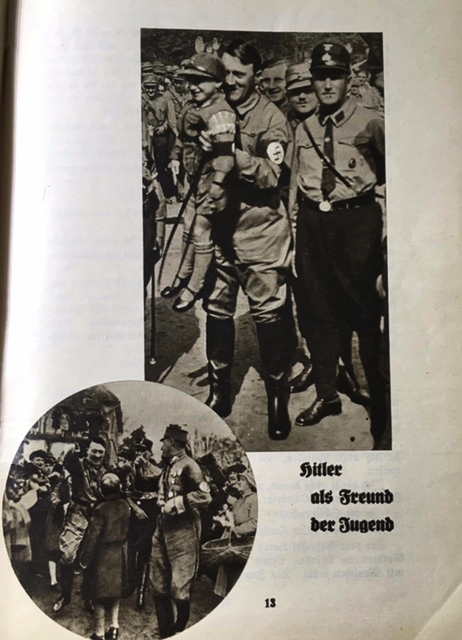

Hitler, Friend of the Youth

Hitler, Friend of the YouthThus the movement grew and grew. He was soon recognized as leader. He knew how to break the opposition’s terror with brute force. An example is the famous battle in the Hofbräuhaus on 4 November 1921, when barely fifty of the protective forces threw out seven or eight hundred Marxists who attempted to disrupt the meeting. This force earned the name Storm Troop or SA.

The German Rally in Coburg in October 1922 is an example of how Hitler led his followers. Czech-Jochberg describes the events in this way:

“There was to be a ‘German Rally’ in Coburg. Hitler was invited to attend.

‘If possible with companions,’ the invitation noted.

Well, those people could be helped: Hitler took as “companions” 1400 men!

It was a kind of trial run. Within an hour they were all at the train station. a special train was ordered and they were off.

There was excitement at every station. There were a thousand questions in the train.. What kind of unit was it? What did the red flags mean? The symbol on them? It was a wonderful propaganda trip. There was a deputation waiting at the train station. They were visibly alarmed. The reception was friendly, but the friendliness was a little strained.

You’re not planning to march in rank....?

Hitler was...

And with flags? There was a written agreement with the Communists and independents that there would be no marching in formation and no flags (in the interests of a peaceful course of the rally).

Hitler answered the gentlemen by asking if they were not ashamed to come to an agreement with such people.

“I have no intention of holding to that agreement. Lead us to our quarters....”

“At the Schützenhalle?” asked one of the unsettled gentlemen.

“If that is to be our quarters?”

The SA gathered in their ranks in front of the station, their flags waving in the wind. The square was already filled with curious people. The unit marched.

But the Marxists ran ahead to worker housing and workplaces.

At first there were jeers and shouts. The way became narrower and the alleys through which the column had to pass smaller. Shouts of “murderers” and “bandits” ... A few policemen hurried up and spoke to the distressed reception committee: “The Schützenhalle? Impossible... Into the city as quickly as possible...”

The unit marched, accompanied by a large mob of howling people. To the Hofbräukeller. The men were stuffed inside and the doors closed to keep out the howling mob.

“Where are our quarters?”

The police did what they could. The quarters were at the edge of the city, it was impossible to get there, there might be fatalities.

The bellowing from outside could be heard inside the hall.

Hitler ordered the police to open the door. That finally happened. The National Socialists marched to the Schützenhaus.

There was nothing but insults. But as they reached the outer district with its construction sites and piles of stones, it suddenly rained stones.

The men separated and stormed the street with such vehemence that the Reds disappeared after a few minutes. No one bothered the National Socialists after that. But there were people missing. Had they run away?

They waited. It grew later. Anxiety grew. They had to be searched for.

Patrols were sent out into the night. They found a man lying in the street, groaning: Individual SA men had been terribly attacked.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

Those on the street the next morning who had no badge were given a leaflet:

“Comrades of the international proletariat!

Murderers have come to our peaceful Coburg and have begun a war of extermination against the workers. Comrades, defend yourselves, drive the rats out of the city. Everyone come to our mass people’s demonstration at the Great Square at 1:30.”

The National Socialists soon had copies.

That could be a pretty event. But it could not be avoided, it must be fought once and for all!

Hitler and his people marched though the quiet city. There were no insults to be heard. Here and there, even shy waves.

Things would begin around the corner.

Each gathered his rage in his fists and marched more quickly so that things would get started sooner.

A few guys were lounging at the corner....

Then one heard laughter from the first ranks that had already gotten to the square. The others soon joined in. The “people’s demonstration” amounted to a few hundred people!”

No one had the courage to insult the ranks. The men from Munich marched calmly, flags flying, through the square and to Coburg Castle.

There was a delay at a side street. Instantly a knot of people gathered. Well! But it was not dangerous as long as the nearby apartment houses stayed neutral.

They stayed neutral. They even cheered as the Reds left.

That evening Coburg was transformed. The square was filled with people, laughing, happy people, who found a kind word for everyone from Munich.

They sang on the way back to the station. To the stationmaster.

Where was the train?

Maybe he had forgotten how to laugh? Finally a few railway men said: ‘It’s over there...”

They laughed in a mocking way and went off.

Into the cars!

But there was no locomotive. To the office again.

“The men refuse to move the train,” the official finally told Hitler.

A bunch of his people are around him. He goes to the next railroad man.

“So you don’t want to transport us?”

Hostile faces with suppressed anger: “No. You know that, why ask?”

“Then we will do it ourselves....”

The railroad men were taken aback, but then laughed.... “Go to hell ... if you go there by train, all to the good.”

“They try to leave, but are suddenly surrounded by a dozen arms.

Hey! You’re going with us. And not you alone. We’ll grab all the Red bigwigs we can and you’ll all go along. If we have an accident, at least a few Reds will meet their end.”

The S.A. men prepare themselves.

“Forward...”

“Hold on....” shouts a railroad man. “I want to talk with my comrades.”

They don’t let him go, nor his comrades. They are taken to the waiting room, the entrances to which are guarded by National Socialists. There is a brief discussion. The leader finally appears: “OK, fine. We’ll go.”

Everybody climbs aboard, including the “guard” (they still do not trust the railroad men).

The locomotive arrives. It is coupled.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

In November 1923, the Bavarian General State Commissioner v. Kahr and his forces attempted to separate Bavaria from the Reich and establish a Danube monarchy under Wittelsbach-Hapsburg rule.

Adolf Hitler dealt with this treasonous attempt on 8 November by forcing in public General State Commissioner v. Kahr, the Bavarian Wehrmacht commander v. Lossow and Police Commissioner v. Seitzer to join with him and General Ludendorff to form a national government.

At first the revolt looked promising. Army troops joined it everywhere. However, it collapsed with General Ludendorff, against Hitler’s clear warning, trusted Kahr, Lossow, and Seitzer and released them from the Bürgerbräukeller.

Despite their words of honor, the three immediately stabbed the uprising in the back. Captain Erhardt also played a dubious role. He is, by the way, the same Colonel v. Seitzer who is now supporting Hindenburg’s candidacy, along with Vorwärts, Ullstein, and Mosse.

On the morning of 9 November, Adolf Hitler marched at the head of the supporters through the city to show the deserters that the whole population stood behind the National Socialists. Singing “Hold Germany in the highest honor,” the column reached the Feldherrnhalle where Seitzer’s police opened fire with machine guns on the singing column and caused a terrible bloodbath. Hitler escaped death by a miracle. Fate had a larger task waiting for him. The resulting trial, in which Hitler took full responsibility for the actions of his supporters, was a triumph for the “accused” and brought eternal shame to the “accusers.” Hitler was imprisoned at Landsberg Prison. During his imprisonment, the movement that had joined with the “German-Völkish Freedom Party” declined rapidly, since it lacked an outstanding leader. There is no better proof of Hitler’s unique leadership nature than that without him, nothing happened. When he was released from prison early in 1925, he reestablished the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. It grew slowly at first, then more rapidly, until it today includes the best part of the whole people in an enormous movement, even though the Führer was prohibited from speaking for years. The German-Völkisch party, however, which did not want to subordinate itself to him vanished from the political scene.

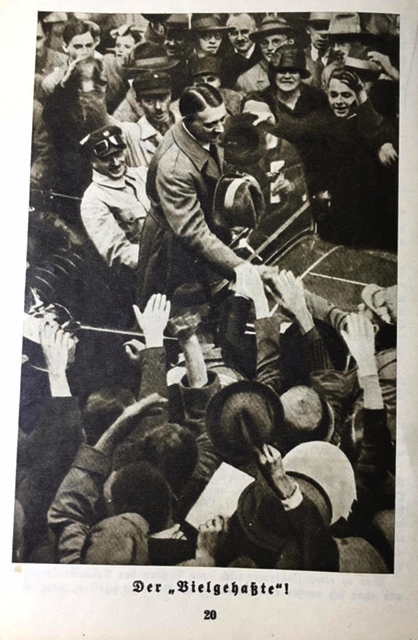

Under Hitler’s leadership the banners of the movement went from victory to victory. As often as one shook one’s head over his actions, even within his own ranks, just as often the Führer had looked far beyond the day’s events and acted rightly. Of the 14 völkisch representatives elected in December 1924, four followed Hitler. Three more joined him later. In 1928 12 National Socialists were elected to the Reichstag, in September 1930 no fewer than 107! Since then election after election in the individual states have shown the movement’s growing strength. Most recently, nearly half the population in Hesse went with Hitler. The people has recognized its true leader. Since the last Reichstag election, party membership has more than tripled. Success in the presidential election is assured by the party’s splendid organization and its exemplary propaganda apparatus.

“Hitler may have developed a popular movement, he may be a brilliant promoter, but he is not a statesman.”

One often hears the know-it-alls say that, although they do not take the trouble to prove that certainly brilliant statement, even though fate has given us enough proof that their statesmanship has plunged us into the deepest chasm.

Not only has the National Socialist Party already used its strong, although voluntary, obedience to develop a state within the state, the leadership of which requires at least as much statesmanship both internally and externally as a government with all its resources, but Hitler already has a higher reputation as a statesman abroad than all of our other “statesmen” combined.

Adolf Hitler proven his abilities as a statesman, and the others have proven even more often that they are not statesman.

Was it statesmanship to sign the Young Plan and then expect the most wonderful relief? Or is statesmanship proved much more by warning against it and all its evil consequences before it was signed?

Was it statesmanship to plan a customs union with Austria, with half-hearted measures and without support from the people or other governments, then to give it up because of foreign objections? [This was a 1931 attempt that quickly went bad.] Or is it much more statesmanly to do as Hitler has done and plan an agreement with Germany, Italy, and England and simultaneously build a phalanx within the people on which one could conduct national policy?

Was it statesmanship before the beginning of the tribute conference, without any support from the people, merely to get the conference indefinitely postponed? Or was it much more statesmanly for Hitler to receive the British press and achieve a strong favorable response to eliminate the tribute, while the government had nothing more urgent to do that to attack Hitler and disavow him.

Countless other examples could be given. These should be enough to show who is the statesman and who the demagogue.

A journalist from Breslau who has known Adolf Hitler personally for many years recently wrote this about Hitler as a person in the Schlesische Tageszeitung:

“Memories from recent years come back, when I had to honor to be editor of his newspaper. It was at a military-political gathering. The speaker was a colonel general. Theme: General Seeckt. The first discussion speaker was General X, the second Lieutenant Colonel Count Y., the third Herr Adolf Hitler. Within a few minutes he had explained the crux of the matter so clearly that nothing was left to say, and a Bavarian dignitary at my table whispered softly: ‘My God, how does the man know that?’ Where intellect and art are to be found in Munich, Hitler is not far distant, and the best minds feel comfortable with him. Who knows that he has been a guest at Haus Wahnfried for years, the friend of Cosima, Siegfried, and Frau Winifred Wagner? Who knows that the immortal author of The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, Chamberlain, sent him a letter ten years ago that said: ‘I had imagined you differently. As I heard you speak for the first time I realized that you did not heat up people’s heads, but rather warmed their hearts!’ Who knows his long and friendly ties to General Director v. Schirach of Weimar’s National Theater? And those with degrees and titles whose blindness leads them to see him as a ‘little man’ should visit the Brown House in Munich, which he himself created, and watch him work for 24 hours. They would be more modest after that!”

He who has once looked in Hitler’s eyes will never forget it. His eyes resemble the famous eyes of Frederick the Great. His expression can be hard as steel one moment, but radiate goodness the next. When he reviews his S.A. men, his gaze seems to penetrate to the deepest depths of each.

In public Hitler may seem a serious and determined fighter, but his warm humor spreads cheer in the circle of his intimates. That is a characteristic that one often finds among great personalities, one that also was typical of Bismarck.

From head to foot, Hitler incorporates the best characteristics of our people, not the least of which is the unshakable loyalty he always shows toward his deserving comrades. Slanders against his tested friends fall on deaf ears.

Perhaps what distinguishes him most of all and earns him the praise of the German people as “Führer” is this: He understands how to draw capable people to his side and shows no envy over their accomplishments. That is the sign of a true leader.

Adolf Hitler alone possesses the human and political characteristics necessary for the leader of the nation of the nation to have if he is to lead it out of its misery. The people feels and knows that, and therefore it will give its vote in the Reich presidential election only to this one man:

[The next two pages contain the party platform]

Page copyright © 2016 by Randall Bytwerk. No unauthorized reproduction. My e-mail address is available on the FAQ page.

Go to the pre-1933 Page.

Go to the German Propaganda Home Page.