Background: This page includes sections of a book on Nazi Party history in Gau Westfalen-Süd, one of a number of local party histories that appeared during the Nazi era. The book runs to 600 pages, so I am translating sections that I find most interesting.

The book begins with a hymn of praise for Gauleiter Josef Wagner, who resigned his post in 1941 and was expelled from the Nazi Party. He was later arrested, apparently because he had sympathies with the 1944 attempt on Hitler’s life and died under unclear circumstances in April 1945. If you read German, further details are available here. It includes details on various party organizations, developments in the towns of the region, and various stories.

The author, Friedrich Alfred Beck (1899-1985) received a Ph.D. in 1935 and was a prolific Nazi author. He was unrepentant after the war.

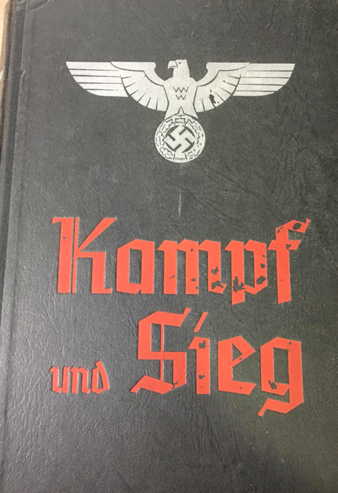

The source: Friedrich Alfred Beck, Kampf und Sieg. Geschichte der Nationalsozialistischen Deutschen Arbeiterpartei im Gau Westfalen-Süd von den Anfängen bis zur Machtübernahme (Dortmund: Westfalen-Verlag, 1938).

by Friedrich Alfred Beck

The introductory paragraph is a good example of how the Nazis saw Germany at the beginning of the movement:

The last shells of the vast battle between peoples blended in with the shots of the Marxist revolution of 9 November 1918. The great battle was over. After four years of heroic struggle the German front was defeated not by the enemy, but by a Marxist stab in the back at home. Bismarck’s Germany was defeated. The mob ruled in Berlin and Munich, in Hamburg and Dresden, in the industrial centers of the Ruhr, Saxony, and Upper Silesia. Returning soldiers and officers of the old glorious army had their cockades and shoulder straps torn off. Women who had lost their men carried the red flag of destruction through German cities. Robbery and murder were daily occurrences. The triumph of insanity seemed total. For four years Germany sent its best sons to all the world’s battlefields for the sake of freedom. Now the opposite of this heroic attitude manifested itself in terrible ways. That was possible because the Jewish poison of Marxism had been injected for decades without limit into the people’s body. The spirit of decay triumphed in Germany on 9 November 1918. Total despotism and slogans that lacked any content rotten guided an inwardly corrupt citizenry that had long since ceased to be carriers of a dynamic and constructive idea capable of building and maintaining a state. The reasons for the collapse that led to a dreadful era of German misery in every area was clear long before the outbreak of the war to thinking and unprejudiced people. Yet the few warning voices went unheard. Fate had to take its course. The German people’s rise on 2 August 1914 was great and powerful, but its narrow-minded circle of leaders who were responsible for the state lacked all greatness. The reason was found in the fateful thinking displayed in a sentence of the last Hohenzollern Kaiser: “I no longer know any party.” [p. 47]

The last shells of the vast battle between peoples blended in with the shots of the Marxist revolution of 9 November 1918. The great battle was over. After four years of heroic struggle the German front was defeated not by the enemy, but by a Marxist stab in the back at home. Bismarck’s Germany was defeated. The mob ruled in Berlin and Munich, in Hamburg and Dresden, in the industrial centers of the Ruhr, Saxony, and Upper Silesia. Returning soldiers and officers of the old glorious army had their cockades and shoulder straps torn off. Women who had lost their men carried the red flag of destruction through German cities. Robbery and murder were daily occurrences. The triumph of insanity seemed total. For four years Germany sent its best sons to all the world’s battlefields for the sake of freedom. Now the opposite of this heroic attitude manifested itself in terrible ways. That was possible because the Jewish poison of Marxism had been injected for decades without limit into the people’s body. The spirit of decay triumphed in Germany on 9 November 1918. Total despotism and slogans that lacked any content rotten guided an inwardly corrupt citizenry that had long since ceased to be carriers of a dynamic and constructive idea capable of building and maintaining a state. The reasons for the collapse that led to a dreadful era of German misery in every area was clear long before the outbreak of the war to thinking and unprejudiced people. Yet the few warning voices went unheard. Fate had to take its course. The German people’s rise on 2 August 1914 was great and powerful, but its narrow-minded circle of leaders who were responsible for the state lacked all greatness. The reason was found in the fateful thinking displayed in a sentence of the last Hohenzollern Kaiser: “I no longer know any party.” [p. 47]

Comments on party organization and speakers:

Even during the Kampfzeit, it was not in the nature of National Socialism to build an organization with countless officials. Aside from the fact that the necessary financial means were lacking, such bureaucratic machinery contradicts the spirit and activism of the Kampfzeit. The Reds who held power made sure that such an apparatus could not be built. And that was good, since otherwise the frequent visits by the police and bans would have had much worse effects on a large administrative apparatus. Since the organization was guided by a small number of active men, they were able to maneuver quickly. Nearly all of those responsible for the organization also belonged to the party’s speaking staff.

They did not sit for hours in their ‘offices,’ but worked in the Gau for weeks and months as speakers and organizers. As a result, the subordinate organizations of the party were constantly in direct contact with Gau headquarters. Problems in county and local organizations could always be solved immediately on the spot. During the day, Gau officials and the Gauleiter’s staff worked to build the party. In the evening, the same men spoke to local groups.

The Führer once said that great events in world history were not primarily the result of the written word, but much more of great speakers. As many both within and outside our borders granted before the takeover of power, we had the best speakers a party ever had. One reason is that our organization had gathered the best racial elements, and thereby the best people from the standpoint of intellect and character. Furthermore, without any demagogy, National Socialism incorporated the fundamentals of our ethnic existence, which according to the laws of nature we must follow in order to stand upright before each other and history. In short, the fact that our idea was justified by the laws of life lead many party members to becoming early fighters for the movement.

There was, of course, National Socialist speaker information material then, but there was probably not one speaker who did not develop his own speeches. Despite the unified line, they had a personal note that was an expression of the speaker himself. The movement would never have won over the German people in the midst of the storm if propaganda speeches had only been matters of the intellect. It is hardly ever possible to win over an opponent only through logical argument, since intellect is only the surface layer of a person’s internal nature, never able to achieve changes in worldview. Speakers who cannot establish a direct connection to their audience will always be bad propagandists, regardless of how elegant, grammatical, and logical they may be. We had a speaker in Gau Westfalen-Süd who never finished a sentence. He usually swallowed the predicate and immediately plunged into a new thought. Nonetheless, he was one of our best propagandists. National Socialist speeches were not schoolroom exercises, but rather passionate affirmations of our eternal mission that spoke with primitive force about our idea.

One thing is clear: there was no one in Gau Westfalen-Süd who could match the speeches of Gauleiter Wagner in form or content. His speeches were masterpieces of a state-philosophic spirit clothed with all the techniques of traditional rhetoric. It was always astonishing to see how these speeches, which never departed from their high level and intellectual depth, were still able to move and captivate the simplest people. The few party members who were there at the time are reminded of the political overviews that the Gauleiter provided each week at the Hochschule fur Politik. Here his masterful command of artistic-political discourse came to greater expression than in a mass meeting.

Party comrade Emil Stürtz, the current Gauleiter of Kurmark, was a speaker we all remember for his independence and uniqueness. His speeches were characterized by pitiless directness and cutting logic, a weapon he used with ruthless cynicism against his opponents. Although he obviously adhered to the Führer’s order to stay within the law, his intellectual sharpness gave the System [the Nazi term for the Weimar Republic] significant wounds. One could call such speeches intellectual fencing; it was nonetheless an intellectually organized and unforgiving battle against a criminal world.

Current Vice-Gauleiter Heinrich Vetter spoke to thousands of meetings. Thanks to him, many Germans from the working class came to National Socialism. His speeches were never superficial, but rather corresponded to the immediate need and carefully prepared. It was always surprising to hear what powerful material he brought against his opponents, and how he cut through their empty phrases. He knew from personal experience the misery of German workers and was the enemy of empty words and academic abstraction. One felt living decency and camaraderie pulse through his speeches.

It is impossible to list all the Gau’s other diligent speakers. They all did their National Socialist duty to the utmost, sometimes to the point of physical or nervous collapse. Everything that the enemy press wrote about the pay they received back then was pure lies. We knew better. Often a speaker somewhere in Sauerland spoke to three, four, or five meetings, sometimes having only a slice of bread and butter to eat. He might have but 40 pfennig in his pocket, only to discover that train fare to the next village was 60 pfennig. He would walk until he reached the point where the fare was 40 pfennig. One Gau speaker had the following experience after a meeting, which is typical of the attitude of propagandists and comrades back then. The speaker had been in Sauerland for a week and had not a pfennig left in his pocket. The county leader could not help help cover even his expenses. He devised a plan to borrow an ox from the farm where the country leader was employed and attach it to a rattletrap DKW [an old German make of car]. That is how he got to Arnsberg. Our old party comrade Dr. Heinrich Teipel would certainly have allowed him to have the animal slaughtered so that he would have the funds to get back to Bochum. However, party comrade Oberlandesgerichtsrat Robert Keimer, current Gaurichter in Arnsberg, gave selfless and generous assistance.

Current National Socialist mass meetings have appropriate decorations. A worthy setting of the entire space is taken-for-granted. Back then, some districts were unable to rent a hall or a barn, since the clergy in the area denied eternal salvation to any who supported National Socialism. It was progress when we could present our thoughts to people in a village while standing behind a pub table alongside the barkeeper who was pouring and selling beer. Often we presented our idea behind a makeshift lectern, a swastika flag draped over it, a few sprigs of green alongside. The battle for National Socialism in those parts of Sauerland controlled by the Center Party seemed hopeless. That did not diminish our drive. Even if we made no progress from one election to the next, the gentlemen had to know that we were still there and would never capitulate.

The situation in industrial districts was entirely different. At first our enemies controlled the meetings. However, only in exceptional cases were they able to disrupt our meetings. If we had enough S.A. men to stretch across the hall, we knew from experience that no one would be able to disrupt the meeting. Our speakers could carry on against the enemy’s superiority only because we refused any discussion. [German political meetings often included a discussion period after the speech.] We implemented the Führer principle, ruthlessly and brutally if necessary. The leader of the Bochum S.A. at the time, party comrade Otto Voß, was a master at such violence. He was a brave fighter.

Our speakers at that time did not only stand before political meetings. We used every opportunity to advertise, speaking at cultural events, to lawyers, doctors, teachers, and at public places on any sort of platform, at weddings and funerals. A National Socialist speaker had to be able to do anything. It might happen that a speaker spoke in the morning at a party comrade’s wedding, at a party comrade’s funeral in the afternoon, then at a women’s meeting, then to the NS student group, and at 3 a.m. in the morning to NSBO [the Nazi labor organization] waiters. Many today have no idea of what that involved.

After large mass meetings, members usually met in Bochum’s Hotel Zur Krone, run by old party comrade Gerhard Günnewig. Today he heads the restaurant at the Düsseldorf main train station. The party’s leadership corps gathered after hard battles, discussing experiences and happenings, joys and disappointments, and found together the strength to begin the next day’s work with new courage.

There were also many district leaders [Bezirksleiter] in Westfalen Süd who were not on the official list at the Gaupropagandaleitung, but nonetheless did their duty day after day somewhere in the countryside. They walked over hill and dale through all sorts of weather. In the early years, these men had to do almost all the speaking in their areas by themselves. Section leaders [Sektionsleiter] did the same. Since they were well-known in their areas, they had to face the worst local battles. All in all, Gau Westfalen-Süd’s speaker staff was the avant garde of our region who can be proud of achievements that equal those of any other Gau. [pp. 79-83]

The book includes summaries of the party’s development in nineteen towns. I translate one typical account.

Unna belongs to Hellweg County.

The National Socialist German Workers’ Party was founded in Unna in December 1922 or spring 1923. The local group consisted of a few members of the dissolved Schutz- und Trutzbund (Alfred Roth, Hamburg) and some young men enthused about Adolf Hitler’s movement who met in the backroom of Waldemar Malaika’s pub in Königsborn. There were only 16 men. The only ones left are party comrades Meinert and his wife, Dorpmüller, Krufe, and Felling. The others have disappeared. The propaganda brigade was not large, but carried the Führer’s’s message to the people with determination. The party comrades had no great successes at the time, however. The middle class parties did not understand them and the Marxists held them in contempt. Given that situation, some party comrades limited their activity to defensive activities against the French who had occupied the Ruhr. They had frequent encounters with the famed Severing police, who conducted house searches and interrogations in vain. Comrade Böing even fell into the hands of the French and suffered the harshest mistreatment in Dortmund. He was sentenced to ten years imprisonment and a fine of 50,000 gold marks for endangering the occupation troops. Party comrades were cheered by news in fall 1923 about a revolt in Munich. Five comrades prepared to go to Munich. Due to the infamous betrayal of 9 November 1923 their plans came to naught. After the dissolution of the party on 10 November 1923, they waited for developments. After a short while they called themselves the Großdeutsche Volksgemeinschaft. They kept cautious distance from the völkisch groups that were surfacing everywhere. They did join with the Völkisch-Sozial bloc for the 4 May 1924 election. That is how party comrades Meinert and Dorpmüller became Reichstag candidates. As a result of that honor, they set to work with paste and brush. They began making propaganda and hanging posters quickly. They had planned a meeting in Nordhaus on 1 May. As they watched the Marxists who were celebrating May Day march past, they saw that their work had had great success. They were greeted with jeers everywhere. The mood in the packed hall seemed so relaxed that a large number of police were sent away. After they had left, it turned out there were stones and smelly packages of toilet waste ready to be used.

The local group worked to the utmost during the election, and afterwards propaganda continued, based on the experiences of the campaign. When the Führer was released from prison in December 1924 and was holding discussions with various politicians, local group Unna sent party comrade Hermann Esser a message that local group Unna stood united behind Adolf Hitler and awaited his orders. A letter went to headquarters on 1 March 1925 with this message: “Best wishes on the first speech by our Führer. The local group unanimously joins the NSDAP and subordinates itself to Gauleitung Westfalen.” The Gauleiter then was Captain von Pfeffer. The old party was re-established and appeared before the public. In conjunction with other local groups it undertook propaganda marches, held public meetings, organized discussion events, distributed leaflets, hung posters, and attempted to secure press coverage. The results were hardly encouraging. Party comrades were first looked at with astonishment, then laughed at and mocked. In opponents’ meetings they were called green youngsters, dreamers, swastika idiots. When they got on the nerves of their Red opponents, there was sometimes a fight and they were thrown out of the hall. Such experiences, however, made them hard, preparing them for the difficult battles that lay ahead. Gradually they began to have success. They were noticed. The enemy spied on them. The Red city government made difficulties in renting halls and banned meetings. The Jews promoted boycotts of party comrades. Here and there, there were fights with whipped up Marxist supporters. Up to this point, defending speakers, meetings and marches was an obvious duty for all party comrades. Then Captain von Pfeffer, and above all party comrade Viktor Lutze, established the S.A. in Gau Westfalen. The local group felt particularly close to Gau S.A. leader Viktor Lutze, since after Lutze was seriously wounded in the war he served as lieutenant and adjutant of the Substitute Battalion Infantry Reserve, Regiment 15, in Unna until the end of the war. He experienced the outbreak of the revolution in Unna, which he said deeply shook him. Just as everything in the movement began small, so it was with the S.A. in Unna. When our party comrade Reich Minister of Propaganda Josef Goebbels spoke at a public meeting in Unna shortly before he moved to Berlin as Gauleiter, no more that 16 S.A. men could be gathered from Hamm and Unna. The meeting was packed with over 1200 people, mostly Marxists. There were about 400 members of the Reichsbanner [the Socialist Party’s paramilitary group] under the leadership of their county leader Lehnemann. The meeting took an unruly course, but party comrade Goebbels was able to finish his speech despite numerous interruptions. During the discussion period it became clear why so many Reichsbanner men were there. The Jew Rosenberg had been in touch with the local Reichsbanner headquarters. Supported by so many followers, discussion speaker Strehl’s remarks were full of agitation. Nonetheless, the meeting ended without fist fights and was a notable success. The National Socialists concluded after this meeting that in the future, troublemakers and provocateurs would be ruthlessly thrown out, regardless of their political coloration. It is impossible to report all the meetings and events over the course of the years, but at least the names of the speakers should be noted. They were the most effective allies of our party comrades during the struggle for power. Who cannot remember the names of our party comrades Wagner, Stürtz, Goebbels, Meister, Himmler, Kaufmann, Zilkens, Vetter, Leibold, Kerrl, Land, Meinberg, Prince August Wilhelm, Schepmann, Voß, Spangemacher, Röver, Beck, Kasche, Sappke, Wiegand, Stein, Diehl, Kleiner, Münchmeyer, König, Heise, Schemmann, Hamacher, von Els, Jeß, Lindner, Ellerstick, Lütt, Paul Meier, Husing, Ahelmann, Frau Dr. Auerhahn, Frau Baltes, and last but not least, our old fighter Franz Bayer with his Storm 83. Party comrades also founded new local groups in the area. A meeting was held in the nearby city of Kamen, which soon resulted in the foundation of a local group. The Stutzpünkte in Frömern and Massen also became independent, formerly belonging to Unna. If one reviews the years between 1923 and 1931, one must conclude that they were really years of preparation for the struggles that led to the Führer’s takeover of power.

Here is a brief review of how the party behaved during the terror bans. The National Socialists announced a public meeting on 18 February 1930 at the Tonhalle and invited Mayor Dr. Emmerich to attend through letters and posters. One hour before the meeting was to begin, the police appeared and announced that the meeting had been banned under the General Law of 1794 since it was a danger to public safety. Party comrades were not cowed. Within a few minutes S.A. men were standing next to the police with signs announcing to the gathering crowd that a new meeting would be held in the Harmony Hall. The crowd was enormous. One could imagine that everything with legs had come, excepting the mayor, even though a leather chair with black-red-gold cushions had been reserved for him. Party comrade Rudolf Zilkens spoke of the contemporary conditions, and a generally peaceful and happy mood prevailed. A large number of people applied to join the party. Things were different at the opponent’s meeting with its Red bigwigs. They held a peace meeting with Unna’s pacifists and the Iron Front [an anti-Nazi coalition] lead by their apostle Schönaich. SPD chairman Wilhelm Hellwig opened the meeting and threatened that the Nazis would be ejected from the hall if they did not behave. After peace apostle Schönaich spoke about just about everything, including Africa and its jungles, the hall erupted in laughter. This unexpected development so alarmed the pacifists that they called on the police, whom they had arranged to have present since they did not feel safe under the protection of the Reichsbanner. As the police marched in to separate the public from the meeting organizers, amusement the likes of which had not been seen before in Unna broke out. In the back of the hall people climbed on tables and chairs so as not to miss the sight of disciples of peace who were now under the protection of the armed forces — which they were generally ready to march against with their tracts. During the discussion period, front soldier Mahnken from Hagen accused former General Schönaich of high treason. He told the story of the ox who was greatly feared by other animals because of its horns. After it voluntarily gave up its natural weapons, things went poorly. There was foot stomping, laughter, and thundering applause as Meinberg said the speaker was an even greater ox who wanted to do the German people what had been done to the ox in the fable. Afterwards, the angel of peace stayed away from Unna. This meeting ended peacefully, but there were enough other ones that came to blows. Party comrade Felling was beaten up while hanging posters. Party comrade Felling spent several weeks in the hospital because of his injuries. The same month, two party comrades from Storm 83 suffered knife injuries at the Spangemacher meeting and had to be brought to the hospital. There were several injuries at the Knesebeck meeting at the Harmony Hall. There was a serious incident during the last Reichstag election in 1932. There was a German Rally in Bergkamen to which ten party comrades from the S.A. and S.S. were heading on bicycles. A troop of 100 Reichsbanner men were coming down Kamenerstrasse. As the S.A. comrades met them, they were thrown from their bicycles and surrounded. member Ferkau was killed by his own people during the fight. Although this was clear to those involved, the SPD used it during the election in the crudest way. Party comrade and S.A. man Karl Scholland was arrested. The accusation soon fell apart and Scholland was released after a few days. The Reds’ lack of conscience was shown as they tried to use their false accusations even on election day to win votes. In subsequent court proceedings the guilty Reichsbanner man was determined and punished. A particular example of unity was the last propaganda march of 1932 through the city’s streets. There was reliable information that the red mob had gathered to disrupt and break up the march. As they reached Market Square the theater began. The Muscovites shouted: “Down, down, Nazi band, murders of workers, slaves of capital, traitors,” and other such phrases. When they began throwing stones, the party comrades lost patience. Instantly, there was a huge battle in Market Square. The speaker’s platform was in ruins, its pieces serving as weapons of defense. The police had not expected things to go peacefully, so they had a large brigade ready. Their quick action restored order. After it was established that none of the comrades was seriously injured, helmets and straps were put in order and the march continued. This march finally made it clear to the Reds who controlled the streets. [pp. 349-355]

Page copyright © 2017 by Randall Bytwerk. No unauthorized reproduction. My e-mail address is available on the FAQ page.

Go to 1933-1945 Page.

Go to the German Propaganda Archive Home Page.