Background: Before Germany declared war on the United States after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the German Library of Information in New York distributed a free weekly newsletter. This one was published after the fall of France. It is interesting first as an official German account of the French campaign, and also as a summary of Nazi arguments against the Treaty of Versailles. I have acomplete collection of these.

The source: Facts in Review, 2 (1940, Nr. 30), July 22, 1940.

Chancellor Hitler’s Headquarters have released a detailed report on the Second German Offensive in France, which began on June 5 and ended when, on June 25, the Armistice went into effect. “Facts in Review” herewith presents an authorized translation of this historic communiqué.

The battle of annihilation in Flanders and Artois had scarcely ended when a second decisive assault on France was launched by the Air Force and the Army. Many divisions which had not seen previous fighting went into action.

Preceding the

new operations was the attack on airports and airplane armament factories

near Paris. This was carried out on June 3 by strong units of the German

Air Force and resulted in the destruction of the objectives. Three units

of the German Army under the command of Colonel General von Brauchitsch

were ready for action the next day. They were headed by Colonel Generals

von Rundstedt, von Bock, and Ritter von Loeb. The objective of this

new offensive was to break through the northern French front, to throw

the enemy forces back to the southwest and southeast, and after splitting

them, to accomplish their annihilation.

Preceding the

new operations was the attack on airports and airplane armament factories

near Paris. This was carried out on June 3 by strong units of the German

Air Force and resulted in the destruction of the objectives. Three units

of the German Army under the command of Colonel General von Brauchitsch

were ready for action the next day. They were headed by Colonel Generals

von Rundstedt, von Bock, and Ritter von Loeb. The objective of this

new offensive was to break through the northern French front, to throw

the enemy forces back to the southwest and southeast, and after splitting

them, to accomplish their annihilation.

Collapse of the French West Wing

The divisions under Colonel General von Bock, who advanced for attack across the lower Somme and the Oise-Aisne canal on June 5, were confronted by an enemy who was prepared to defend himself. The French Command was resolved to stake all its remaining forces for a last-ditch defense of the “Weygand Zone” and of its next position, the Maginot Line. A new method of defense had been devised, of which it was, above all, hoped that it would succeed in preventing the dreaded, rapid breakthrough of motorized units. In four days of heavy fighting, infantry and armored divisions of the armies under Colonel Generals von Kluge and von Reichenau and General Strauss (Infantry) forced their way through the enemy front. On June 9, pursuit in the direction of the lower Seine and Paris was in full progress. Rapidly advancing troops commanded by Infantry General Hoth reached Rouen on the same day and began the encirclement of strong enemy forces on the coast near Dieppe and St. Valéry. The enemy’s west wing was thus smashed and our west flank protected for the main operations which now ensued.

As in previous fights, the concentrated and energetic direct mass attacks of the Air Force here, too facilitated the success of the Army, particularly in the quick breakthrough to the Seine. Even as they gathered for the advance, the infantry and armored units which had been assembled there in preparation for the French counterthrust were routed by air bombing. The destruction of railroad tracks and rolling stock deprived the enemy of his means for shifting reserves and moving them up to the breach.

With the first sign of impending evacuation at Le Havre, Cherbourg and Brest, Air Force units, striking in rapid sequence, made successful attacks upon oil depots, harbor facilities and ships.

Launching the Main Land Operations

The main land operations were begun on June 9, when Colonel General von Rundstedt’s army attacked at Champagne and on the west bank of the Meuse. Infantry divisions belonging to the armies of General Baron von Weichs (Cavalry), Colonel General von List and General Busch (Infantry) attacked with excellent support from the Air Force. During two days’ heavy fighting against a desperately resisting enemy, they broke through the Aisne position and cleared the way for the powerful rapid units that had been held in readiness. As early as June 11, the armored and motorized infantry divisions of Cavalry General von Kleist and General Guderian (Armored Troops) entered the battle at Champagne, their objectives being points far beyond Troyes and St. Didier. For the third time in a quarter of a century German troops advanced across the Marne. Fighting with enemy rear guards was heavy at first; later, parts of the main army were taken completely by surprise. In the next few days, the mobile troops poured through the huge breach that had been effected and forced southeast toward the Swiss border. The evolutions carried out in such a small territory by such a large number of infantry divisions and mobile units were a unique accomplishment.

The Fall of Paris

Meanwhile, our troops sped across the lower Seine and broke into the Paris defense positions. The enemy’s west wing was thus also compelled to forego further resistance. On June 14, General von Küchler’s troops (Artillery) entered Paris. The enemy’s northern front had collapsed; a general rout was in progress everywhere. Infantry divisions and mobile units vied with each other in covering vast distances. Symptoms of the dissolution of the opposing armies, which were unable to withstand the terrific pressure, increased by the hour. On June 14, Colonel General Ritter von Loeb’s Army was thrown into action. In two days of heavy fighting against powerful fortifications, Colonel General von Witzleben’s Army, strongly supported by artillery, broke through the Maginot Line, France’s reputedly impenetrable wall. The enemy’s northeast line, already threatened from the rear, was thus again split in two, and what little remained of the enemy’s belief in his ability to resist was shattered.

The eastern French front met a similar fate when, on June 15, General Dollman’s Army (Artillery) stormed the formidable Upper Rhine fortifications in an attack near Colmar and forced its way into the Vosges Mountains. Fighting in perfect coordination with the Army, the Air Force helped materially in achieving the quick break through the Maginot Line south of Saarbruecken, and later near Colmar and Muelhausen. Whenever weather permitted, Stuka and fighter units attacked and silenced the fortifications with heavy bombs. Anti-aircraft units also gave the attacking infantry highly effective support. Simultaneously, other Air Force units helped mobile troops force their way ahead to Besancon and the Swiss border.

An Unprecedented Rout

After June 15, the campaign became a rout such as has never been seen before, from the sea coast to the Meuse. After the fall of Paris, French columns, in retreat to the south and southwest along the whole German front line, were attacked again and again by German fliers. Dogged pursuit on land and from the air frustrated the French plan to take up new positions below the Loere River.

Our divisions-inspired by victory and the reparation, at last, of the wrongs of Versailles-rolled on over the ruins of the defeated French army. Not even the fortress of Verdun, the symbol of French resistance in the World War, was able to hold out. It fell on June 15.

On June 17, mobile units reached the Swiss border southeast of Besancon, closing the circle around the Maginot Line and the French forces in Lorraine and Alsace. Bold attacks across the Loire revealed that here, as elsewhere, the enemy was no longer able to pull himself together for further resistance. The Armies of France had lost their fighting power and were beginning to lay down their arms.

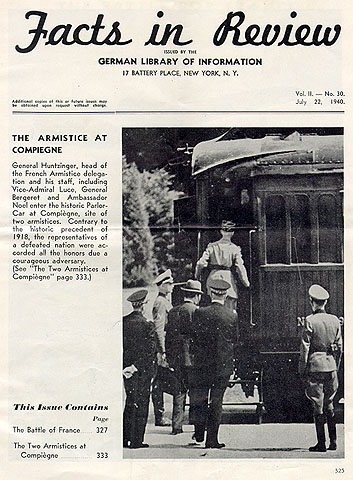

This situation forced Marshal Pétain, the French Premier, to apply to the German Government for an armistice. On June 21, in the historic Compiégne forest, a solemn act by the Führer and Supreme Commander of the Defense Forces wiped out the iniquity of 1918. The French delegation received the armistice terms from the Chief of the High Command, and the armistice was signed at 6:50 p.m. on June 22. At 1:35 p.m. on June 25, the German and Italian defense forces ended hostilities against France. The greatest victory of German forces, culminating the greatest campaign of all times, had been concluded within six weeks. How much the Air Force helped win these exceptionally quick decisions has already been told in the High Command’s communiqué on the first phase of the Campaign in the West. Co-operation during the second phase was no less valuable.

Supremacy of the Air Force

The Air Force, commanded by Field Marshall Goering, made full use of the supremacy it secured at the beginning of the campaign. These battles were fought in the main by Air Fleets 2 and 3, energetically and ably led by Generals Kesselring and Sperrle (Air Force). An intrepid and indefatigable spirit was demonstrated by the leaders and men of the high air force and anti-aircraft units headed by Generals Grauert and Keller (Air Force), General Weise (Anti-Aircraft Artillery), Lieutenant Generals Bogatsch, Ritter von Grein, Loertzer, and Major Generals Coeler, Dessloch, and Baron von Richthofen. The army is wholeheartedly grateful for the unselfish readiness of the Air Force to sacrifice itself in the heaviest of fighting.

The Role of the Navy

With the occupation of the Dutch, Belgian and French Channel coast, the Navy faced new tasks. Following the Army operations, the harbors were developed into bases for light naval forces and equipped for defense. From these harbors, speedboats were brought into action in areas which had not been accessible to them before and which, since they were close to the coast, afforded particularly good opportunities for such craft. In an endless series of attacks, speedboats succeeded in sinking a number of enemy destroyers and transport vessels, thus intensifying and supplementing the effectiveness of the Air Force’s assault on the fleet of enemy transports which had been brought up for the evacuation of Dunkerque. As early as June 6, the coast defense entrusted to Naval Artillery forces reported its first success, the sinking of a British speedboat. Minesweepers cleared the harbor entrances and ship lanes near the conquered coast. As early as June 8, neutral ships could once more sail from Dutch, Belgian and Northern French harbors to German, Danish, Swedish and other Baltic ports.

Meanwhile, the activities of our U-boats near the British Isles and the French coast met with considerable success.

How Was It Done?

This unparalleled victory of German arms has aroused in some, admiration and astonishment; in others, terror-depending on the individual point of view. But the universal question is: How was such a tremendous success won in so short a time? If the former Allies feel that the reason was German superiority in numbers, their view does not coincide with the facts. It is true that the German Air Force held a considerable numerical superiority over that of the Allies. But the German Army of the West began its attack on May 10 with fewer divisions than there were French, English, Belgian and Dutch divisions opposing it. Furthermore, operations in the West, unlike the Polish campaigns were not begun from favorable strategic positions. Frontal attacks by the German troops against exceedingly strong fortifications, most of which were located behind rivers or canals, had to force the break-through preliminary to the surrounding and annihilation of the enemy and to the bringing up of further divisions. The reason for the German success lies deeper.

This reason is what Germany’s enemies believed was her weakness: the revolutionary, dynamic character of the Third Reich and National Socialist leadership. This spirit has created the best of modern fighting machines, with an energetic, centralized Supreme Command. It has found the synthesis between sober well-considered and painstaking preparation, on the one hand, and, on the other, utmost daring in the carrying out of operations. It raised the German soldier’s famous fighting power to a level which could not have been reached through the driving force of patriotism alone. That fighting power can only be explained by the presence of an idea which engaged the entire united nation. All officers, down to the lowest ranks, in the Army as well as the Air Force, practiced personal leadership to an admirable degree. Fighting in the front lines on the ground, at the head of their formations in the air, they were the inspiration of their troops and squadrons. Boldly, with resolution and presence of mind, they took advantage of every situation without hesitation.

The Remarkably Small Casualty List

Lieutenant General von Speck died a hero’s death at the head of his Army Corps. Between June 5 and 25, 16,822 brave officers, non-commissioned officers and men of the three forces likewise gave their lives for their Führer, their people, and their Reich. 9,921 officers, non-commissioned officers and men are missing. Undoubtedly some of these also died heroes’ death. 68,511 officers, non-commissioned officers and men were wounded.

One of the most glorious features of the German victory over France is that it was achieved with such small losses. These losses are felt bitterly and painfully by the individual; but to the German people as a whole they are almost incredibly small.

The figures to date, for the period from May 10 to the Armistice, are as follows:

Killed 27,074

Missing 18,384

Wounded 111,034 Officers, non-commissioned officers, and men.

Total Casualties 156,492 Officers, non-commissioned officers and men.

Compare this with the following casualties suffered by us during the World War:

In the West in 1914: 85,000 of 638,000 men were killed. In the attack on Verdun in 1916: 41,000 of 310,000 men were killed. In the Somme Battle in 1916: 58,000 of 417,000 men were killed. In the great Battle of France, March 21 to April 10, 1918: 35,000 of the 240,000 men were killed.

The Huge French Losses

There is as yet no exact basis for estimating the enemy’s casualties in 1940. The number of French prisoners alone is more than 1,900,000, including five Commanders of French Armies and 29,000 officers. Besides the material captured before June 5, all the arms and equipment of approximately 55 additional French divisions was taken. This does not include the armament and equipment of the Maginot Line and the other French fortifications. Furthermore, nearly all of France’s heavy artillery and immeasurable quantities of other arms and equipment were captured.

Since June 4, the enemy Air Force suffered the following losses:

In air fights, 383 airplanes; by anti-aircraft artillery, 155; destroyed

on the ground, 239; lost through undetermined causes (by anti-aircraft

fire or in air fights), 15 airplanes; total planes lost, 792. Also destroyed

were 26 barrage balloons and one captive balloon.

On June 14, an interceptor unit brought down its 101st enemy plane; on

June 11, a pursuit unit its fiftieth.

The Navy sank the following auxiliary cruisers and other auxiliary naval vessels, transports and merchant ships:

The auxiliary cruiser “Carinthia” of 23,000 gross tons, the

auxiliary cruiser “Scotstown” of 17,000 gross tons, the troop

transport “Orama” of 21,000 gross tons, the navy oil tanker

“Oil Pioneer” of 9,100 gross tons, one transport ship of 14,000

gross tons, one auxiliary cruiser of 9,000 gross tons.

Merchant ships sunk by our U-boats since the middle of May aggregate more

than 400,000 gross tons, which, with the ships listed above, bring the

total up to 493,100 gross tons,

Since June 5, the Air Force has sunk: one auxiliary naval vessel and one destroyer, with a combined total of 5,100 gross tons, and 40 merchant ships aggregating 299,000 gross tons.

The following were damaged: 3 cruisers, 1 destroyer, 25 merchant ships.

Besides these tremendous losses of the enemy, the remnants of the French forces have, through the terms of the Armistice, also been eliminated for the rest of the war.

Since this most sensational victory in German history-a victory over an opponent regarded as the world’s strongest land power, an enemy who fought skilfully [sic] and bravely-the Allies have been non-existent. Only one enemy remains: England.

On June 17, France asked Germany and Italy for an armistice. On June 22, such an agreement was signed with the German delegates, and on June 24, with the Italians. Hostilities ceased in the early morning hours of June 25.

Many regard the armistice conditions as particularly harsh. Evidently, those who hold this position have forgotten the conditions which Germany was forced to accept in November, 1918, on exactly the same spot at Compiégne when the French Generalissimo, Marshal Foch, was the spokesman for the Allies.

That Armistice was followed by the Treaty of Versailles, an instrument infinitely more severe than the pact of Compiégne.

A short history and comparison seem essential before pronouncing a verdict.

I. THE ARMISTICE OF JUNE, 1940

The Armistice, signed on June 22, 1940 between Germany and France, makes sure that France will not take up arms against Germany. Most of the French territory, occupied for the time being, was gained by military action. Sections of the French coast which were not conquered will be occupied only for the duration of the war between Germany and Great Britain.

Germany does not demand, as the pact of Compiégne in 1918 did, delivery of locomotives and other railway-stock. She only wants guarantee of safe transportation between the occupied territory and Italy.

Delivery of weapons and equipment is required only in so far as they are found in the occupied territory. The extent of delivery of weapons in unoccupied territory is not yet decided.

Germany does not demand the evacuation of French troops from French colonies, as the Armistice of 1918 did in regard to German East Africa. All that Germany asks of the French fleet, including submarines, is that it be demobilized and immobilized under German control. But Germany has not demanded any unit of the French fleet for herself. Provisions have even been made for the protection of French interests in her colonial empire. Units needed for these duties are not required to demobilize.

Germany must be notified of the location of mines and other harbor and coastal obstructions. Wholesale destruction is not demanded.

French prisoners of war will be released after the conclusion of a peace.

Those who read the following pages, dealing with the first Compiégne agreement and Versailles, and study the conditions of the second Compiégne will not fail to notice a great difference not only in the actual conditions, but in the conduct of the victorious power. Marshal Pétain said, “These are severe conditions, but at least our honor is saved.”

From France, Italy demands only demilitarisation of a zone extending 50 kilometers beyond the Italians’ most advanced line on the French-Italian front; the demilitarisation of naval bases in the Mediterranean; harbor and railway facilities near Italian colonial possessions; and in localities situated elsewhere, the demilitarisation of a limited zone of French possessions. Only border territories of the French colonies are effected. These total about 56,000 square miles, whereas the French possessions in Africa cover a territory of 4,272,000 square miles.

No one can foretell the terms of the final peace treaty with France. One can assume that these will depend on French willingness to establish good relations with Germany and Italy during the transitional period. France has a chance to show her good will in 1940; such a chance was denied to Germany in 1918-19. France was conquered, Germany was not. France, if she had been victorious, would have imposed armistice and peace terms on Germany which would have left precious little of the Reich intact. The ink has not yet dried on speeches demanding the dismemberment and annihilation of Germany. The Reich laid down her arms in 1918 confident that the promises for a just and impartial peace would be kept. In view of all the facts, conveniently forgotten by Germany’s critics, the terms imposed upon the French are both just and generous.

II. THE FOURTEEN POINTS OF 1918

On January 8, 1918, the President of the United States, Mr. Woodrow Wilson, addressed Congress. In this famous speech he stipulated the 14 points which he considered the corner-stones of the coming peace.

They were:

I.-Open covenants, openly arrived at, after which there shall be no private international understandings of any kind, but diplomacy shall proceed always frankly and in the public view.

II.-Absolute freedom of navigation upon the seas outside territorial waters, alike in peace and in war, except as the seas may be closed in whole or in part by international action for the enforcement of international covenants.

III.-The removal, so far as possible, of all economic barriers and the establishment of an equality of trade conditions among all the nations consenting to the peace and associating themselves for its maintenance.

IV.-Adequate guarantees given and taken that national armaments will be reduced to the lowest point consistent with domestic safety.

V.-Free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based upon a strict observance of the principle that in determining all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the population concerned must have equal weight with the equitable claims of the Government whose title is to be determined.

VI.-The evacuation of all Russian territory and such a settlement of all questions affecting Russia as will secure the best and freest cooperation of the other nations of the world in obtaining for her an unhampered and unembarrassed opportunity for the independent determination of her own political development and national policy, and assure her of a sincere welcome into the society of free nations under institutions of her own choosing; and more than a welcome, assistance also of every kind that she may need and may herself desire. The treatment accorded Russia by her sister nations in the months to come will be the acid test of their good-will, of their comprehension of her needs as distinguished from their own interests, and of their intelligent and unselfish sympathy.

VII.-Belgium, the whole world will agree, must be evacuated and restored, without any attempt to limit the sovereignty which she enjoys in common with all other free nations. No other single act will serve as this will serve to restore confidence among the nations in the laws which they have themselves set and determined for the government of their relations with one another. Without this healing act the whole structure and validity of international law is forever impaired.

VIII.-All French territory should be freed and the invaded portions restored, and the wrong done to France by Prussia in 1871 in the matter of Alsace-Lorraine, which has unsettled the peace of the world for nearly fifty years, should be righted, in order that peace may once more be made secure in the interest of all.

IX.-A readjustment of the frontiers of Italy should be effected along clearly recognizable lines of nationality.

X.-The peoples of Austria-Hungary, whose place among the nations we wish to see safeguarded and assured, should be accorded the freest opportunity of autonomous development.

XI.-Rumania, Serbia, and Montenegro should be evacuated; occupied territories restored; Serbia accorded free and secure access to the sea; and the relations of the several Balkan States to one another determined by friendly counsel along historically established lines of allegiance and nationality; international guarantees of the political and economic independence and territorial integrity of the several Balkan States should be entered into.

XII.-The Turkish portions of the present Ottoman Empire should be assured a secure sovereignty, but the other nationalities which are now under Turkish rule should be assured an undoubted security of life and an absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development, and the Dardanelles should be permanently opened as a free passage to the ships and commerce of all nations under international guarantees.

XIII.-An independent Polish State should be erected which should include the territories inhabited byundisputablyPolish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea, and whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by international covenant.

XIV.-A general association of nations must be formed under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.

President Wilson Demands” Impartial Justice”

On February 11, 1918, President Wilson spoke again before the Congress and laid down four principles which had an even more peaceful ring. He repeated them at Mount Vernon on July 4, 1918.

On September 27, 1918, President Wilson gave an address in New York on “War Issues and the Peace Program.”

“If it be indeed and in truth the common object of the Governments associated against Germany and of the nations whom they govern, as I believe it to be, to achieve by the coming settlements a secure and lasting peace,” Wilson declared, “it will be necessary that all who sit down at the peace table shall come ready and willing to pay the price, the only price that will procure it; and ready and willing, also, to create in some virile fashion the only instrumentality by which it can be made certain that the agreements of the peace will be honored and fulfilled.

“The price is impartial justice in every item of the settlement, no matter whose interest is crossed; and not only impartial justice, but also the satisfaction of the several peoples whose fortunes are dealt with.”

III. THE BASIS FOR NEGOTIATIONS

During the night of October 4-5, 1918, the German Government appealed to President Wilson for an immediate armistice. This appeal contained the sentence: “The German Government accepts as a basis for the peace negotiations the program laid down by the President of the United States in his message to Congress of January 8, 1918, (The Fourteen Points) and in his subsequent pronouncements, and of the German Government of October 12, which contained the cautious assumption: “The German Government believes that the governments of the powers associated with the United States also accept the position taken by President Wilson in his address.”

On October 14th Mr. Lansing again requested confirmation of the same points and the German Government again assented in a note of October 20.

On October 23, the President informed the Allied Powers of this exchange of notes, and, through Mr. Lansing, he sent another note to Germany, stating that he wanted to make absolutely sure that the internal change which had meanwhile occurred in Germany, would secure a safe basis for negotiations. Otherwise, Germany would not be permitted to negotiate, but would have to surrender. The answer of the German Government on October 27th was in the affirmative.

To Germany, waiting for a definite answer to her appeal for an armistice, this repeated exchange of notes spelled a delay. But this delay, after all, assured Germany that President Wilson regarded his own points and pronouncements as the only basis for conclusion of an armistice and the subsequent peace.

The negotiations from October 5th to 23rd were carried on solely between the United States and Germany. Eleven more days passed before Allied acceptance of Wilson’s basis for peace was assured.

The powers finally accepted the same basis as Germany with one or two reservations. President Wilson’s adviser, Colonel House, hastened this decision with the menace of a separate peace between the United States and Germany.

At last,one month after Germany’s appeal for an armistice, the famous Lansing Note of Novemeber [sic] 5, 1918, was sent to Germany. In this note, which was special weight as a preliminary peace treaty, Secretary of State Lansing informed the German Government that the Allies had accepted the same basis with two exceptions. The second of the Fourteen Points on the freedom of the seas, was changed at England’s request. The allies, i.e., France, also demanded that Germany not only evacuate the occupied territories but restore them. Point 2, incidentally, had been especially stressed by President Wilson in his “Peace Without Victory” address before the American Senate on January 22, 1917.

Meetings at Compiégne

On November 7, the German plenipotentiaries left the German Headquarters at Spa. In the morning of November 8 their train stopped on a siding in the middle of a clearing in the Forest of Compiégne, opposite a special train containing Marshal Foch’s parlor car.

When the German delegates had entered his coach Marshal Foch came in, accompanied by General Weygand, Chief of the French General Staff, and some other French officers and by the British Admiral Sir Rosselyn Wemyss and his naval staff. Introductions were short and icy. Marshal Foch turned to his interpreter, “Ask these gentlemen what they want.” The head of the German delegation replied, “We have come to accept the proposals of the Allied Powers for an armistice on land and sea and in the air.” When the word “proposals” was translated, Foch at once rose from his chair and it looked as if he was to break up the meeting. “Tell these gentlemen,” Foch said, “that I have no proposals to make to them.” But he consented to go on with the meeting, the General Weygand announced the 34 points of the armistice conditions. The time limit allowed for the decision of the German negotiators was 72 hours and the answer requested was acceptance or rejection without modification.

The suggestion to cease hostilities immediately was rejected.

On their own authority, the plenipotentiaries would neither accept nor reject such hard terms. Therefore, they sent a member of the staff back to the German Headquarters in Spa to ask for a decision.

During the final discussion between General Weygand and General von Winterfeldt, Foch came into the compartment and said irritably, “Haven’t you finished yet? If you haven’t finished in a quarter of an hour, I’ll come back and I promise you we shall finish in five minutes.”

Because no word came from the messenger who had been sent back to Spa, the plenipotentiaries asked for an extension of the time limit. Twenty-four hours more were requested, but Foch sent back word immediately: “Not a moment longer than 72 hours.”

On the night of November 10, a wireless communiqué from General Headquarters at Spa stated that Field Marshal von Hindenburg raised substantial objections to the terms, including a demand for lifting the starvation blockade. These were cast aside. The German plenipotentiaries were compelled perforce to sign.

IV. THE ARMISTICE TERMS

Capitulating completely, Germany laid down all her arms and means of defense. Foch could say to Clemenceau, “Here is my armistice. Now you can conclude any peace you like. I am in a position to execute it.”

Six hours after the signature, at 11 o’clock a.m. on November 11, 1918, the guns became silent. From that moment Germany was powerless and at the mercy of her enemy.

The conditions of the Armistice concluded between the Allies and Germany were:

(a) The Western Front

I. Cessation of hostilities on land and in the air six hours after the signing of the Armistice.

II. Immediate evacuation of invaded countries-Belgium, France, Luxembourg,

also Alsace-Lorraine-so ordered as to be completed within 15 days from

the signature of the Armistice. German troops which have not left the

above-mentioned territories within the period fixed will become prisoners

of war.

Occupation by the Allied and United States forces jointly will keep pace

with evacuation of these areas.

All movements of evacuation and occupation will be regulated in accordance with the Note determined at the time of the signing of the Armistice.

III. Repatriation, beginning at once, to be completed within 15 days, of all inhabitants of the countries above enumerated.

IV. Surrender in good condition by German Armies of the following equipments: 5,000 guns (to wit 2500 heavy and 2500 field), 25,000 machine guns, 3,000 mine throwers, 1700 fighting and bombing aeroplanes-primarily all the D 7’s and all the night bombing machines. The above to be deliveredin situto the Allied and United States troops.

V. Evacuation by the German Armies of the districts on the left bank of the Rhine. These districts shall be administered by the local authorities under the control of the Allied and United States armies of occupation.

The occupation of these territories by Allied and United States troops will be assured by garrisons holding the principal crossings of the Rhine (Mayence, Coblenz, Cologne) together with bridgeheads at these points of a 30-kilometer (about 19 miles) radius on the right bank, and by garrisons similarly holding the strategic points of the regions.

A neutral zone shall be set apart on the right bank of the Rhine between the river and a line drawn parallel to the bridgeheads and to the river, and 10 kilometer (6 _ miles) deep, from the Dutch frontier to the Swiss frontier.

Evacuation by the enemy of the Rhine districts (right and left bank) shall be so ordered as to be completed within a further period of 16 days, in all 31 days after the signing of the Armistice.

VI. In all territories evacuated by the enemy, all evacuation of inhabitants shall be forbidden; neither damage nor harm shall be done to the persons or property of the inhabitants.

No person shall be prosecuted for having taken part in any military measures previous to the signing of the Armistice.

No destruction of any kind shall be committed.

Military establishments of all kinds shall be delivered intact, as well as military stores of food, munitions and equipment, which shall not have been removed during the periods fixed for evacuation.

Stores of food of all kinds for the civil population, cattle, etc., shall be leftin situ.

No measure of a general or official character shall be taken which would have as a consequence the depreciation of industrial establishments or a reduction of their personnel.

VII. Roads and means of communication of every kind, railroads, waterways, roads, bridges, telegraphs, telephones shall be in no manner impaired.

All civil and military personnel at present employed on them shall remain so employed.

5,000 complete locomotives, 150,000 wagons in good working order with all necessary spare parts and fittings, shall be delivered to the Associated Powers within the period fixed in Appendix No. II, the total of which shall not exceed 31 days.

5,000 motor lorries are also to be delivered in good condition within 36 days.

The railways of Alsace-Lorraine shall be handed over within 31 days, together with all personnel and material belonging to the organization of the system.

Further, working material in the territories on the left bank of the Rhine shall be leftin situ.

All stores and material for the upkeep of permanent way, signals and repair shops shall be leftin situand kept in an efficient state by Germany, as far as the means of communication on the left bank of the Rhine are concerned.

All lighters taken from the Allies shall be restored to them.

VIII. The German Command must reveal, within 48 hours after the signing of the Armistice all mines or delayed-action engines laid within the territories evacuated by German troops, and shall facilitate their discovery and destruction.

IX. The right of requisition shall be exercised by the Allied and United States Armies in all occupied territories, excepting payment to those who are entitled thereto.

The upkeep of the troops of occupation in the Rhine districts (excluding Alsace-Lorraine) shall be charged to the German Government.

X. The immediate repatriation, without reciprocity, according to detailed conditions which shall be fixed, of all Allied and United States prisoners of war, including those under trial and already convicted. The Allied Powers and the United States of America shall be able to dispose of these prisoners as they think fit. This condition annuls all previous conventions regarding prisoners of war, including that of July 1918, now being ratified. However, the repatriation of German prisoners of war interned in Holland and Switzerland shall continue as heretofore. The repatriation of German prisoners of war shall be settled at the conclusion of the peace preliminaries.

XI. Sick and wounded who cannot be removed from territory evacuated by the German forces shall be cared for by German personnel, who will be leftin situwith the necessary material.

(b) Clauses Relating to the Eastern Frontiers of Germany

XII. All German troops at present in any territory which before the war formed part of Austria-Hungary, Roumania or Turkey shall withdraw within the frontiers of Germany as they existed on August 1, 1914. All German troops at present in territories which before the war formed part of Russia must likewise return to within the frontiers of Germany as above defined as soon as the Allies shall think the moment suitable, account being taken of the internal situation of these territories.

XIII. Evacuation of German troops to begin at once; and all German instructors, prisoners and civilians as well as military agents now in the territory of Russia to be recalled.

XIV. German troops to cease at once all requisitions and seizures, and any other coercive measure with a view of obtaining supplies intended for Germany in Roumania and Russia.

XV. Denunciation of the treaties of Bukarest and Brest Litowsk and of the supplementary treaties.

XVI. The Allies shall have free access to the territories evacuated by the Germans on their Eastern frontier, either through Danzig or by the Vistula, in order to convey supplies to the populations of those territories and for the purpose of maintaining order.

(c) East Africa

XVII. Evacuation of all German forces operating in East Africa within a period specified by the Allies.

(d) General Clauses

XVIII. Repatriation without reciprocity, within a maximum period of one month, in accordance with detailed conditions hereafter to be fixed, of all interned civilians including hostages and persons under trial and convicted who may be subjects of Allied or Associated States other than those mentioned in Clause III.

XIX. With the exception of any future concessions and claims by the Allies and United States of America:

Repair of damage done.

While the Armistice lasts no public securities shall be removed by the enemy which can serve as a pledge to the Allies for the recovery of war losses.

Immediate restitution of the cash deposit in the National Bank of Belgium, and in general, immediate return of all documents, specie, stock, shares, paper money, together with plant for the issue thereof, affecting public or private interests in the invaded countries.

Restitution of the Russian and Roumanian gold yielded to Germany or taken by that power. This gold shall be held in trust by the Allies until peace is signed.

(e) Naval Clauses

XX. Immediate cessation of all hostilities at sea, and definite information to be given as to the position and movements of all German ships.

Notification to be given to neutrals that freedom of navigation in all territorial waters is given to the Naval and mercantile Marines of the Allied and Associated Powers, without raising questions of neutrality.

XXI. All Naval and Mercantile Marine prisoners of war of the Allied and Associated Powers in German hands to be returned, without reciprocity.

XXII. The surrender at the ports specified by the Allies and the United States of all submarines at present in existence (including all submarine-cruisers and mine-layers) with armament and equipment complete. Those which cannot put to sea shall be denuded of crew and equipment, and shall remain under the supervision of the Allies and the United States. Submarine ready to put to sea shall be prepared to leave German ports immediately on receipt of wireless order to sail to the port of surrender, the remainder to follow as early as possible. The conditions of this article shall be completed within 14 days of the signing of the Armistice.

XXIII. The German surface warships, which shall be designated by the Allies and the United States of America, shall forthwith be dismantled and thereafter interned in neutral ports, or failing them, Allied ports designated by the Allies and the United States of America. They shall remain there under the surveillance of the Allies and the United States of America, only care and maintenance parties being left on board.

The vessels designated by the Allies are: 6 battle-cruisers, 10 battleships, 8 light cruisers (of which 2 shall be mine-layers), 50 destroyers of the most modern type.

All other surface warships (including river craft) are to be concentrated in German naval bases to be designated by the Allies and the United States of America, completely dismantled and placed under supervision of the Allies and the United States of America. The military equipment of all vessels of the Auxiliary Fleet is to be landed. All vessels specified for internment shall be ready to leave German ports seven days after the signing of the Armistice. Directions for the Voyage shall be given by wireless.*

XXIV. The Allies and the United States of America shall have the right to sweep up all mine-fields and to destroy obstructions laid by Germany outside German territorial waters, the positions of which are to be indicated.

XXV. Free access to and from the Baltic for the Naval and Mercantile Marines of the Allied and Associated Powers; secured by the occupation of all German forts, fortifications, batteries and defense works of all kinds in all the channels between the Kate and the Baltic, and by the sweeping up and destruction of all mines and obstructions within and without German territorial waters the positions of all such mines and obstructions to be indicated by Germany, who shall be permitted to raise no question of neutrality.

XXVI.The existing blockade conditions set up by the Allied and Associated Powers are to remain unchanged, German merchant ships found at sea remaining liable to capture.The Allies and the United States contemplate the provisioning of Germany during the Armistice as shall be found necessary.

XXVII. All aerial forces are to be concentrated and immobilized in German bases specified by the Allies and the United States of America.

XXVIII. In evacuating the Belgian coasts and ports Germany shall abandon in suit and intact the port material and material for inland waterways, also all merchant ships, tugs and lighters, all naval aircraft and air materials and stores, all arms and armaments and all stores and apparatus of all kinds.

XXIX. All Black Sea ports are to be evacuated by Germany; all Russian warships seized by Germany in the Black Sea are to be handed over to the Allies and the United States of America; all neutral merchant ships seized in the Black Sea are to be released; all warlike and other materials of all kinds seized in those ports are to be handed over, and German materials as specified in Clause XXVIII are to be surrendered.

XXX. All merchant ships at present in German hands belonging to the Allied and Associated Powers are to be restored to ports specified by the Allies and the United States of America without reciprocity.

XXXI. No destruction of ships or materials to be permitted before evacuation, delivery or restoration.

XXXII. The German Government shall formally notify all the neutral governments, and particularly the Governments of Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Holland, that all restrictions placed on the trading of their vessels with the Allied and Associated countries, whether by the German Government or by private German interests, and whether in return for special concessions, such as the export of ship-building materials, or not, as immediately cancelled.

XXXIII. No transfer of German merchant shipping of any description to any neutral flag is to take place after signature of the Armistice.

(f) Duration of Armistice

XXXIV. The duration of the Armistice is to be 36 days with power of extension.During this period, on failure of execution of any of the above clauses, the Armistice may be repudiated by one of the contracting parties on 48 hours’ previous notice. It is understood that failure to execute Articles III and XVIII completely in the period specified is not to give reason for a repudiation of the Armistice, save where such failure is due to malice aforethought.

To insure the execution of the present convention under the most favorable conditions, the principle of a permanent International Armistice Commission is recognized. This Commission will act under the supreme authority of the High Command, military and naval, of the Allied Armies.

The present Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, at 5 o’clock (French time).

(g) Additional Stipulations

Two appendices completed the Armistice terms. On the one hand, they outlined the successive steps of the evacuation of Belgium and French territories by the German troops who had held them since August 1914 against the combined power of their enemies. On the other hand, for the time since August 1914, they provided for the occupation of German territory by the Allied powers.Except for small parts of Alsace-Lorraine, the Allies had not previously set foot on German soil.

Appendix II stipulated certain demands for the railway stock, telegraphic and telephone lines and other commodities which partly exceeded the demands of the Armistice terms. Also included were the heavy demands of the Inter-Allied Rhineland Commission and the army of occupation which Germany had to carry out in the following years.

The German plenipotentiaries had to sign the Armistice. There was no way out. But they handed the enemy a written protest, signed by all four of them. In it they promised that Germany would endeavor to execute the obligations imposed upon her.

Germany’s Protest

“The undersigned Plenipotentiaries further regard it as their duty with reference to their repeated oral and written declarations once more to point out with all possible emphasis that the execution of this agreement must throw the German people into anarchy and famine.

“According to the declarations which preceded the Armistice, conditions were to be expected which, while completely safeguarding the military situation of our opponents, would have ended the sufferings of women and children who took no part in the war.The German people who had held their own for fifty months against a world of enemies, will, in spite of any force that may be brought to bear upon them, preserve their freedom and unity.

“A people of 70 millions suffers but does not die.”

Spirit of the Fourteen Points Vanishes

Indeed, there was not much left of the principles upon which the Armistice and Peace were to be based, the principles to which Germany had confidently appealed, the principles upon which she had laid down her arms. The spirit of the Fourteen Points had vanished somewhere in the chilly November days in the forest of Compiégne.

Peace without victory?

Yes, there was no victory for the armies of the Allied and Associated Powers because they had not been able to drive the German armies from France and Belgium while those armies possessed their weapons. Two of the Allied Powers, Roumania and Russia, completely vanquished, had surrendered a year before to Germany.

Germany was not defeated. She was utterly exhausted and starved, her home front weakened partly by the blockade and, partly, by the propaganda campaign of the Allies. She was weary. This war “would end all wars” and the world would be made “safe for democracy.” Taking the promises made to her for granted, she laid down her arms. At the time, she did not know that the Allies, with the exception of the fresh American troops, were equally weakened and weary. What if Germany had made a last effort, rejected the terms of the Armistice and gone on fighting? Germany did not know it at that time: the Allies, too, were desperately in need of an Armistice.

V. THE TREATY OF VERSAILLES

The French Government’s Letter

On November 29, 1918, the French Government sent a letter to Secretary of State, Robert Lansing. This was handed to President Woodrow Wilson on December 2, two days before he sailed to Europe on the “George Washington.” Part of this letter reads:

“The arrival of President Wilson in Paris will enable the four Great Powers to agree among themselves upon the conditions of the peace preliminaries to be imposed severally on the enemywithout any discussion with him.

“The examination will first apply to Germany with which it is to our interest to negotiate at once in orderto promote the disassociation of the countries of which she is composed.

“The peace preliminaries with Germany will furthermore shape the way for the settlement of the main territorial restorations: Alsace-Lorraine, Poland, the Slav countries, Belgium, Luxembourg, the cession of German colonies, the full recognition of the protectorates of France over Morocco and of England over Egypt, the provisional acceptance of the constitution of new independent states out of the territories of former Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires. . . . . The question of peace preliminaries with the other two enemy powers presents itself in a different aspect. With respect toAustria-Hungary, it is not even existentsince that Power has disappeared. The same, of course, applies afortiorito Turkey. . . . . The representatives of the Great Powers will have to come to an agreement on the principles of the representation of the several belligerent, neutral and enemy states at the Peace Congress. . . . . Besides, the distinction is made necessary by the fact that theenemy has no right to discuss the terms that will be imposed upon him by the victors, and that the neutrals will only be called in the exceptional cases to attend the sessions wherethe belligerents will fix the peace terms, while all the peoples, whether belligerents, neutrals or enemies, will be called to discuss and take part in the principle of the society of nations.”

Before President Wilson sailed to Europe, he spoke in Congress on December 2, and said, “The future peace agreements are for us, as for the whole world of the utmost importance. . . . The gallant men of our armed forces by sea and land have consciously striven for the ideals. . . I have endeavored to give expression to those ideals. . . . I owe it to them to see to it that no false or erroneous interpretation is placed upon those ideals and that no possible effort is neglected to realize them.

On that same day, Mr. Wilson received the letter from Paris which is quoted above. No wonder the President had forebodings of what was awaiting him in France. One night on board the “George Washington” he admitted to George Creel, “What my spirit seems to see-and I earnestly hope I may be mistaken-is a tragedy of disappointments.”

The Paris Conference

The Paris Conference opened on January 18, 1919, in Versailles. It was

housed behind barbed wire. The German delegation was invited on April

18. The draft of the Peace Treaty was handed to the German delegation

on the 7th of May. A discussion of the draft did not take place.

The natural resentment with which the German nation received the dictated

terms of peace was certainly increased by the fact thatduring the

whole of the six months from the opening of the Versailles Conference

to the publication of the draft Treaty not a single representative of

Germany was consulted.As the French had announced in their letter

on November 29, 1918, they wouldimposethe conditions, notdiscussthem.

The Terms of the Treaty

But all this was only an ugly frame. The picture enclosed in this frame was even more ghastly.

The Treaty of Versailles far exceeded the conditions of the Armistice. It was not a peace treaty, but an act of revenge, destined to dismember and to cripple German territory, population, armed forces and economic life. All too clearly this is shown by the following summary of the main facts.

Part I of the Versailles Treaty is the Covenant of the league of Nations to which Germany was admitted only several years after the Treaty was signed. The very fact that the Covenant was included in the Versailles Treaty threw a dubious light on the League of Nations in the eyes of the Germans who fought for a revision of the Treaty.

Political Clauses (exceeding the Armistice)

Germany was compelled to cede Moresnet, Eupen and Malmedy with 60,000 inhabitants to Belgium after the armistice. This is important proof that France was eager long before the end of the war to acquire these territories and to dismember Germany.

No mention of the Sari Valley was made at Compiégne. At Versailles, Germany had to cede all mines in this rich industrial area with 800,000 inhabitants to France with the right to buy them back after 15 years. Though sovereign rights were assigned to the League of Nations, the actual political power was exercised by France.

At Versailles, Germany was forced to recognize the independence of Austria which could only be changed with the consent of the League of Nations. This clause was a violation of the principle of self-determination, for in her new republican constitution Austria declared herself a part of Germany.

At Versailles, CzechoSlovakia was born, consisting of Bohemia, Moravia with its 3 million Germans and other parts of Austria, inhabited by Slovaks. To this new state, Germany was forced to cede, without plebiscite, parts of Upper Silesia, the so-called Unlatching Blanche, with 200 square miles and a population of 65,000.

According to Point XIII of Mr. Wilson’s program, Poland was to be erected as a country with an un disputably Polish population. In violation of this stipulation Germany had to cede to Poland without plebiscite nearly the whole province of Posen, about two-thirds of West Prussia, and smaller districts of Lower Silesia. A plebiscite was held in Upper Silesia, resulted in a majority of 60% for Germany, but in spite of this the richest part with 74% of the mining and metallurgical industries was ceded to Poland.

At Versailles, Poland demanded parts of East Prussia. Here a plebiscite was granted. In the two sections in question, 92% and 98% of the population voted in favor of Germany. They remained with Germany.

However, the cession of another part of East Prussia was asked, and the town and hinterland of Memel, with 150,000 inhabitants, were taken over by the Allies for the benefit of Lithuania in 1923.

The Poles demanded the city of Danzig. Without a plebiscite, the city and surrounding areas were set up as a “Free City”; it was united with Poland by a customs-union and other provisions.

In the East, the Versailles Treaty deprived Germany of an area of 19,700 square miles and a population of 4,375,000. It was a land rich in agriculture. Upper Silesia especially was noted for its wealth of raw materials and its industrial enterprises.

At Versailles a demand was made for parts of the northern German province of Eschewing. After a plebiscite, a small section was ceded to Denmark; other parts remained German.

Germany was forced to destroy all fortifications in Hegelian, and to recognize the independence of the Russian border states.

A very important feature, not mentioned before, was the loss of the German colonies with an area of 2,954,900 square miles, a white population of 28,396, a colored population of 22,728,000 and the loss of trade amounting to 465 million gold marks in 1912. Some of the Allied Powers received these German colonies as “mandates” under nominal control of the League of Nations. In practice, the conquering nations treated the acquisitions as parts of their own huge colonial possessions.

At Versailles, Germany was compelled to surrender all rights and to yield certain German private properties in her commercial settlements in China, Siam, Liberia, Morocco and Egypt.

Germany was even compelled to give up all her rights and property to two countries with which she was allied during the World War, Turkey and Bulgaria, not in favor of these countries but in favor of the Allied Powers.

Military Clauses

The Versailles Treaty allowed Germany an army of only 100,000, and a navy of 15,000 men, including officers. The General Staff was to be dissolved, conscription to cease. Equipment was limited to the barest necessities. Modern weapons such as tanks were prohibited. Manufacture of the other arms was allowed only in factories known to the Allies. The total equipment as it stood at the time of the signing of the Versailles Treaty was to be delivered to the Allies or destroyed. Fortresses were dismantled.

The German Navy must not exceed 6 battleships, 6 small cruisers, 12 destroyers, 12 torpedo-boats. New battleships built in the future were limited to 10,000 tons. Submarines were prohibited altogether. Germany was not permitted to have or to build any land or sea planes for military purposes.

All obligations were to be carried out under the supervision of an Inter-Allied Control Commission, the expenses of which Germany was compelled to defray during its long existence.

According to the Armistice, prisoners of war of Germany’s enemies were released at once; Germany prisoners of war were held as hostages until the conclusion of peace preliminaries. The United States, Great Britain and Italy released them after the signing; France kept them until the ratification in 1920.

Part VII of the Versailles Treaty called for the delivery of the former German Kaiser and all German Army and Navy leaders. These humiliating demands were not carried out.

Economic Impositions

One of the next articles in the treaty was the infamous Article 231 which saddled upon Germany the sole guilt for the outbreak of the World War. This Article 231 has done more than any other to poison the relationship between Germany and the Allies. It preceded the long list of reparations for “damages” demanded from Germany. Up to 1931 Germany paid 3_ billion dollars in cash. In addition Germany paid the costs of the occupation of the Rhineland.

Germany was compelled to Surrender all sea-going vessels with a tonnage of over 1,600 tons, half of the smaller ones, a quarter of her fishing fleet. She was obliged:

to build merchant-ships for the Allies with a total tonnage of 200,000 tons,

to deliver one fifth of all internal waterway vessels, machines of every kind lost by the Allies during the war (not necessarily losses caused by the war),

to deliver to France 500 stallions, 30,000 mares, 90,000 head of cattle*, 100,000 sheep,

to deliver to Belgium, 200 stallions, 10,000 mares, 50,000 head of cattle, 40,000 heifers,

to deliver building-material, plumbing, furniture, etc. for reconstruction in the war-zone,

to deliver coal, e.g., to France, for 10 years, 7 million tons per annum, to Belgium, 8 million tons per annum, to Italy, quantities of 4, 5 to 8, 5 million tons per annum,

to Luxembourg, a quantity equal to that annually purchased by this country from Germany in peace-time.

(All this after the coal-mines in the Sari went to France for 15 years and most of the coal-mines in Upper Silesia were lost to Poland.)

to deliver to France for 3 years 35,000 tons of gasoline, 50,000 tons of coal-tar, and 30,000 tons of ammonia per annum,

to deliver 25-50% of various chemical products for 5 years,

to deliver her most important cable-lines.

Besides all this the Allies demanded a long list of historic relics and works of art.

Germany had to issue bonds as guarantees for the payment of reparations, to grant to the Allies economic preferences, lost such status for herself, relinquished patent rights, etc., etc., etc.

Germany was forced to give the Allies the same civil air-traffic rights in Germany as Germany herself, to internationalize German rivers, tariffs, harbors, channels, and to hand over certain running rights on German railway-lines.

Signing this Treaty of Versailles was a decision which the German delegates could not undertake without trying every means to alter the provisions. Counter-proposals were made but only minute modifications were gained.

“Oh what a tangled web we weave

When first we practice to deceive!”

Even members of the Allied and Associated Powers protested against the methods applied in Paris, for which Clemenceau was responsible. President Wilson struggled against them. They were entirely different from his own ideas and promises. But he had to give in. Germany, too, finally submitted. Complete acceptance or rejection were the only alternatives. Many Germans would have preferred to reject the Treaty and to bear the consequences. But with the signing of the Armistice, Germany had laid her arms down completely and surrendered all strategic positions.

On June 23rd the German Peace Delegation informed Clemenceau that the German Government and a majority of the National Assembly had decided to accept the Versailles Treaty.

“The German Government has noted with consternation,” the Delegation stated, “from the last communication of the Allied and Associated Governments, that they are determined to exact by force from the German people the acceptance even of clauses in their Peace Treaty which, though yielding no material advantage, are expressly framed to dishonor Germany. German honor cannot be sullied by an act of sheer despotism, though the privation and endurance of four years have bereft us of all outward means of defending it. The German Republic therefore, in submission to the dictates of force, though in no way altering her conviction of the unheard-of injustice of this Treaty, declares herself ready to accept it and sign its conditions as imposed by the Allied and Associated Powers.”

The German peace delegation went back to Versailles. Stones were thrown at its members by the populace.

On June 28, 1919, the signatures were placed under the Treaty. Festivities in France; flags at half-mast in Germany.

The blockade was finally lifted 9 months after the Armistice and 2 months after the signing of Versailles. During that period alone more that 100,000 Germans, mostly aged people, women and children died of malnutrition and starvation. They had managed to survive the war. They could not endure the war after the war.

This was, perhaps, apace without victory, but with a different meaning for the words than when they were first spoken. For it was no peace either. That became clear for the first time at Compiégne. It became even clearer from day to day when the scene was set for the Peace Conference in Paris and when the treaty was signed at Versailles. It forced itself upon the consciousness of the German people in all the years that followed. To the Germans it was not the Peace Treaty, but the Dictate of Versailles.

* On November 20, 1918, 20 submarines were surrendered; on November 21, the German High Seas Fleet of 9 battleships, 5 battle-cruisers, 7 light cruisers and 50 destroyers.

In an appendix to the Armistice document, signed by Marshal Foch and

admiral Wemyss, but without the signatures of the German delegation, specification

was given. It reads: “The following ships and vessels of the German

fleet with their complete armament and equipment are to be surrendered

to the Allies and United States of America Governments, in ports which

will be specified by them, namely:

Battleships: Third Battle Squadron: “König”, “Bayern”,

“Grosser Kürfurst”, “Kronprinz Wilhelm”, “Markgraf”.

Fourth Battle Squadron: “Friedrich der Grosse”, “König

Albert”, “Kaiserin”, “Prinzregent Luitpold”,

“Kaiser”. Batttle-cruisers: “Hinderburg”, “Derfflinger”,

Seydlitz”, “Moltke”. “Von der Tann”, “Mackensen”.

Light cruisers: “Brummer”, “Bremsen”, “Köln”,

“Dresden”, “Emden”, “Frankfurt”, “Nürnberg”,

“Wiesbaden”. Destroyers: Fifty of the most modern destroyers.

* This in spite of the fact that the children of Germany were on the verge of starvation for lack of milk.

Go to the German Propaganda Archive Home Page.